There is an ivory flute in the digital collection of the National Museum, Budapest, which has a very unique history.

This is the so called „Frederick’s flute” – that belonged to Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia (1712-1786). To understand the special history of this precious item, we must to go back to the Seven Years’ War.

The Historical Backround

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) was a significant global conflict involving major powers across Europe, North America, and Asia. It pitted Prussia and Great Britain against Austria, France, Russia, and others. The war stemmed from territorial disputes in Europe, particularly over Silesia, and colonial competition between Britain and France in regions like North America and India. The war concluded with the Treaty of Paris and the Treaty of Hubertusburg in 1763. The conflict had long-lasting effects on global geopolitics, shaping the modern international order.

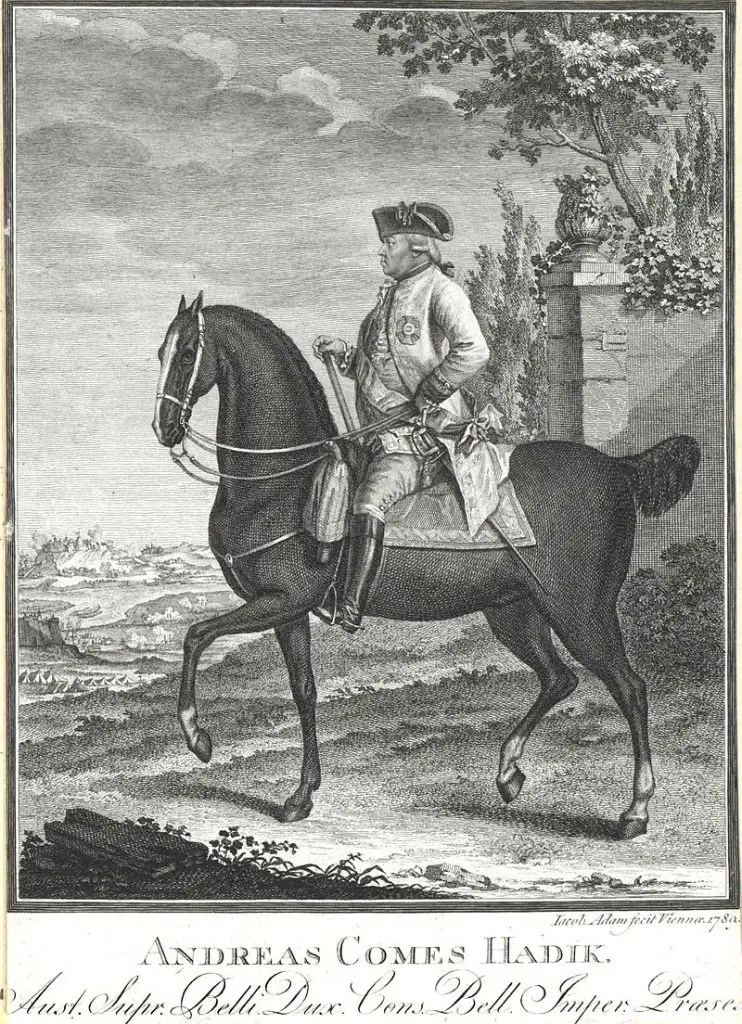

András Hadik (1710–1790), a prominent Hungarian military leader and nobleman who served in the Habsburg Imperial Army. Today he is best known for his daring raid on Berlin during the Seven Years’ War in 1757.

Born into a lesser noble family in Csallóköz, Hungary, although he wanted to be a priest he began his military career in 1732 and quickly rose through the ranks due to his exceptional leadership and strategic skills. He later became the commander of the imperial forces in Silesia and held various high-ranking positions, including President of the Imperial War Council, he was practically became the supreme military leader of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

Throughout his career, Hadik earned numerous honors, such as the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa, and contributed significantly to the military successes of the Habsburg Empire. His legacy remains celebrated in Hungarian history as one of the most skilled and courageous military leaders of his time. Music was often played in his home, and perhaps he practiced it himself.

The Raid

During the Seven Years’ War, in September 1757, Frederick, The Great found himself in a difficult situation and he must left the main theater of war, Silesia and Bohemia, and then camped at Erfurt in a central location, from where he could maneuver in any direction in the event of an enemy attack.

The imperial-royal commander-in-chief, Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine (the younger brother of Maria Theresa’s husband, Emperor Francis I), correctly perceived that there was a significant gap between the Prussian main army retreating westward and the other Prussian force securing Silesia. He believed that a brave raid could reach the almost undefended Prussian core area, Brandenburg, which would mean a great loss of prestige for Frederick. He entrusted General András Hadik with the planning and execution of the task, which required boldness, discipline and precision.

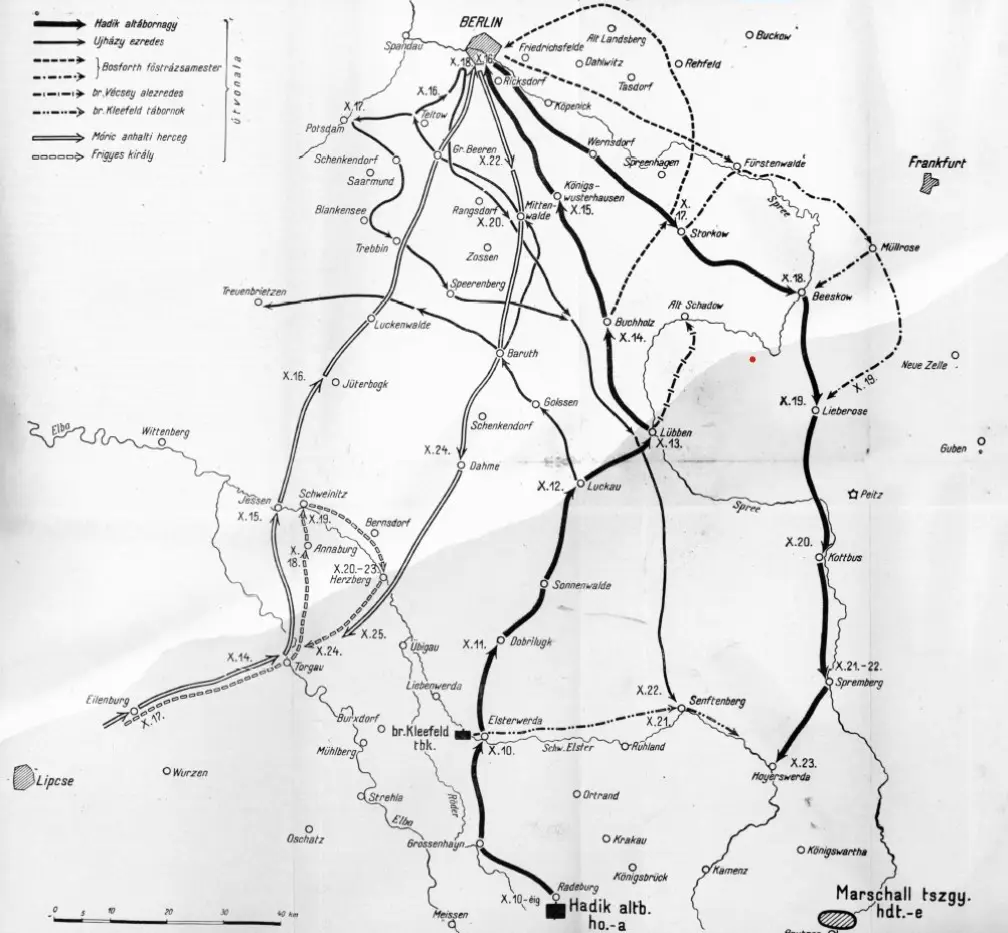

During the so called „Berlin-raid” General Hadik led a force of 4,500 soldiers to capture the city and impose a ransom, showcasing his ingenuity and bravery. Although it is often referred to today as a „hussar prank”, it was a very sophisticated, carefully planned operation. The fast-moving unit was self-sufficient, without supply lines, carrying only 4 cannons.

Alone Hadik knew the purpose and details of the attack. The soldiers were forbidden to take any violent action against the otherwise hostile population, food had to be bought for money, they were not allowed to drink alcohol. They had to be constantly ready for battle day and night and must move as fast as possibile. He set off on October 10 with his hussar troop and demanded extremely strict discipline, as the enterprise required maximum strain from both the soldiers and their horses. He transported the infantry on horseback – so two men sat on a horse – they mostly moved at night and had to cover 70-80 km per day.

Hadik arrived near Berlin on 15 of October, more precisely at Königs-Wusterhausen, the royal castle where Frederick spent his childhood. It is very likely that he took the flute with him here. (He also took with him Frederick’s childhood boots, which were in the Hadik family’s possession for a long time, even in the first half of the 20th century). It is fair to assume that there must have been a logical reason for this action, at least insofar as he wanted to surprise one of his friends with them. A flute is not necessarily an interesting object, a spoil for a general, unless he himself or one of his friends can play it.

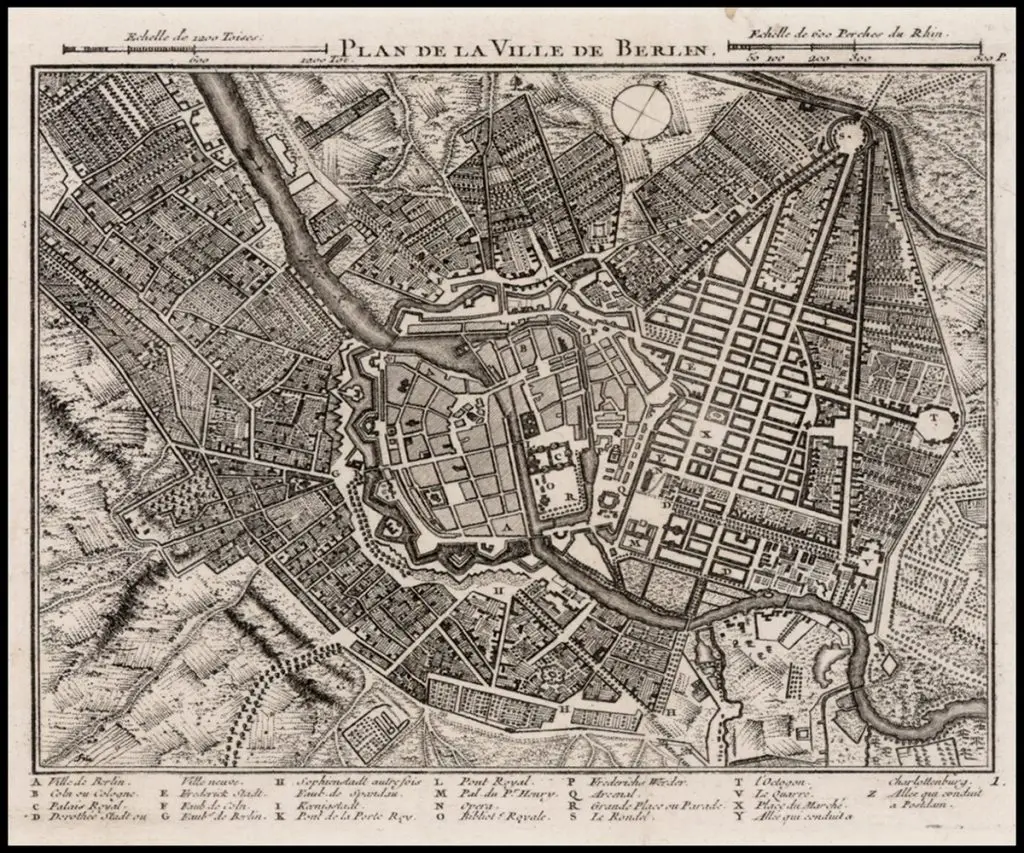

András Hadik’s troops reached the walls of Berlin at noon the next day and demanded a huge ransom from the city. The city council tried to negotiate, but Hadik didn’t give them any chance, he shot through the Silesian Gate and took the city. Although the defenders were outnumbered – because the hussars had left a significant part of their 4,500-strong force behind them as defenders, they gave up the fight after a shorly. Here too, Hadik did not allow his soldiers to plunder freely, as was customary at the time, but concentrated only on the ransom.

The military men left Berlin on the 18th and on the 21st met Colonel Újházy in a safe area, who – as a diversion – treated Potsdam in a similar way. Hadik distributed most of the tribute among his soldiers. The brilliant undertaking brought maximum shame to one side, while maximum success to the other, and András Hadik received the Grand Cross of the Order of Maria Theresa. Throughout history, only the Red Army, apart from Hadik’s hussars, was able to take Berlin.

The Flute

The „Frederick’s flute” was made in ivory, in Paris and it is tipical four part flute from this era. Dr. Klára Radnóti, a senior researcher at the National Museum and a museologist, wrote about the flute’s further journey in Hungary: Hadik gave the flute to a friend, Colonel Jósika (who did not take part in the Berlin adventure). He then gave it to his brother, Pater Jósika of the Piarist Order. From then on the flute was with the Piarists – and after his death, the provincial superior Zsigmond Orosz took it over, who – after removing the decorative gold rings and presumably the gold keys – gave it to Father Ignác Blahó. In 1784, he entrusted the flute, which had already been damaged by two cracks, to Father Elek Szenczy, who also had another flute.

After that, the flute remained in the Piarist Museums for the rest of its life, from 1818 it was placed in Vác, and then from the beginning of the 20th century in National Museum, Budapest. Benedek Csalog and later Barthold Kuijken was able to examine the flute. As I learned from Benedek Csalog, the flute was made by a not very well-known Parisian musician named Cornet.

During my research on the this flute, I found another interesting piece of information that was published the Bulletin of the Piarist Order – however this has no direct connection with the „Frederick’s flute”. According to the Bulletin János Cörver (1715-1773), the provincial superior of the Piarist Order in Hungary, not only visited Frederick’s court, but also played with him some chamber music as well. We can read this in the publication:

“ He [Czörver] was a highly educated man; he was fluent in Hungarian, German, Italian, French, Latin and Greek. He gave lectures in Italian in Rome and Naples, wrote a book in French and corresponded in five languages. Staying in Paris for a longer period, he visited the court of Louis XV several times. He won the friendship of King Frederick In Berlin, and, being able to play the flute artistically, he played together with King Frederick.”

Source: The history of the Piarist college in Budapest, Budapest, 1894-95

Today the adventurous „Frederick’s flute” only can see via digital, see the link below.

Sources:

Military History Publications 1941 (Volume 42. Budapest, 1941) Árpád Markó: Lieutenant General András Hadik’s Berlin venture (Arcanum)

The flute in the digital collection – https://gyujtemenyek.mnm.hu/hu/record/-/record/MNMMUSEUM1465792

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi

www.czeloth.com | ORDER BOOK “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration“

Mr. Czeloth-Csetényi, Gyula plays the flute since his age of 10. He went to the Bartók Conservatory, then he studied at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. After the demolition of the iron curtain he was the first to visit Sir James Galway’s Seminar from Hungary in Switzerland between 1993 and 1995. He was Dr. Jochen Gartner’s student at the Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich.

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi has made his first CD recording of Gamal Abdel-Rahim’s compositions there. He graduated “Cum Laude” in 1997 at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. Between 1990 and 1999 he has been the editor and publicist of the journal of the Hungarian Flute Association. Beside his classic repertoire he plays at a jazz band where his own compositions are performed, too. He played together with recognized jazz musicians.

As classical flutist he has performed all over Europe and in Japan. He made a solo CD in 2001, its title is “12 Romance”. He is a co-lead author of the book under title – “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration”. The book was published in 2022.