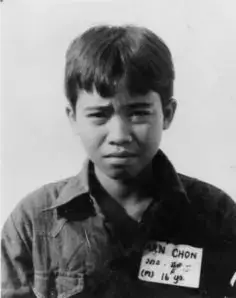

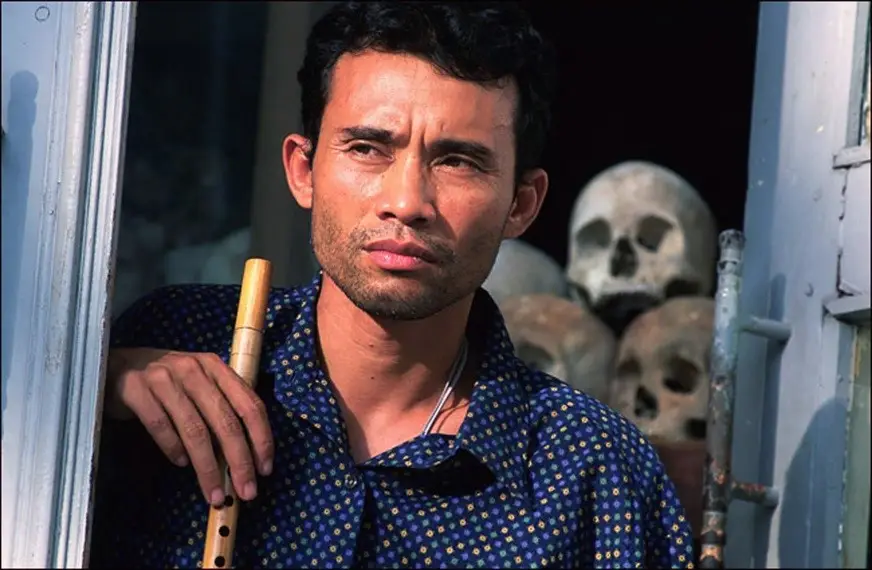

In a Cambodian temple turned into a killing camp, a frightened boy once raised his hand. The Khmer Rouge officer had asked if any children could play music. For most, it was a trap that could mean death. But for Arn Chorn-Pond, that hand in the air became the difference between life and execution. He was given a flute, a few days of hurried lessons, and an impossible order: play or perish.

The year was the mid-1970s, and Cambodia was under the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge, a radical communist regime led by Pol Pot. Determined to create a classless agrarian society, the Khmer Rouge abolished schools, religion, and the arts, and executed or starved to death nearly two million people between 1975 and 1979. Families were separated, intellectuals and artists were targeted, and children like Arn were swept into camps where survival was a daily gamble.

Music as Survival

Arn was separated from his family and sent on a forced march to a Buddhist temple converted into a killing camp. Along the way he saw people collapse and die, possessions abandoned in the dirt, and bodies left unburied. “In just one day a person can get used to seeing dead bodies,” he later said. “Over and over I told myself one thing: never fall down.”

At the camp, 700 children labored from dawn until midnight without food. They were forced to watch executions, sometimes to even push victims into mass graves. Arn remembers: “Three or four times a day they would kill people and force us all to watch. If you didn’t do what the Khmer Rouge told you to do, they’d kill you too.”

Arn’s skill spared him when others perished. The music he was forced to play glorified violence and was sometimes used to mask the sound of executions. Yet even amid horror, the flute gave him a fragile escape. “It helped me to escape the hell, the killing,” he recalls. “Whenever I was given the opportunity to practice, I would escape with the sound of the instrument to heaven — to another place.”

At only 12 years old, his flute was taken away and replaced with a gun. Forced into the Khmer Rouge army, Arn watched friends fall in battle until he finally fled across the jungle to Thailand. Emaciated and traumatized, he weighed barely 30 pounds when he reached a refugee camp. There, an American pastor adopted him and brought him to the United States, giving him the chance to rebuild his life.

Rebuilding Through Music

Life in America was another kind of trial. Arn barely spoke English and was bullied in school. His adoptive parents urged him to tell his story. His adoptive mother patiently taught him English word by word until he could share the truth of what he had endured. Speaking was painful—“like poking on your own wounds,” he said—but it became his mission. He wanted young people to understand not only the horrors of the genocide but also the way music had kept him alive.

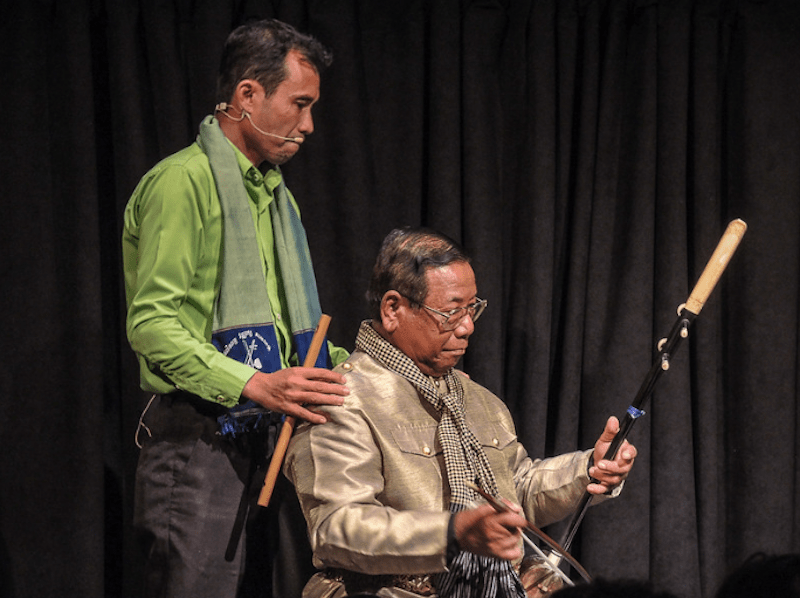

When he returned to Cambodia years later, Arn searched for surviving master musicians. Against all odds, he found his teacher Youen Mek and others who had lived through the regime. Together they began training children in Cambodia’s traditional music, planting seeds for a cultural revival.

This effort grew into Cambodian Living Arts, which today supports performers, scholarships, and festivals across the country.

Passing the Torch

Arn’s story is now coming to Ipswich because of Reilly Miner, a recent graduate of Ipswich High School and a gifted oboist. Miner first learned of Arn through the Winthrop family, who support both the Orchestra on the Hill and Cambodian Living Arts. They saw a natural connection between the young musician and the survivor, and introduced them.

For Miner, the meeting was transformative. Coming from a family where even renting an instrument was a stretch, he had already experienced firsthand how music could be a refuge during hardship. Hearing Arn speak about surviving genocide through the power of music gave Miner a new perspective on his own struggles.

That encounter is the reason Arn will now perform in Ipswich. Miner’s connection built the bridge, and their shared belief in music as a lifeline has become the heart of this collaboration. When Miner plays his oboe in the orchestra beside Arn’s flute, he will not just be performing music — he will be carrying forward the message that one person’s survival story can inspire another’s resilience.

Another Survivor, Another Song

Arn’s story is extraordinary, yet not isolated. Across the world, survivors of atrocity have turned to music as their lifeline. One such figure was Alice Herz-Sommer, a pianist and Holocaust survivor. Imprisoned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, she played more than 100 concerts for fellow prisoners, believing that music gave them strength when everything else was gone. She later said: “Music was our food. Music was life.” Herz-Sommer lived to 110 years old, the oldest Holocaust survivor at the time of her death.

Like Herz-Sommer, Arn embodies the truth that music is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit — something that nourishes, protects, and sustains life in the most desperate times.

A Universal Lullaby

Today, Arn often ends his appearances by playing a lullaby on the flute. For decades he performed it solo, but this season he will join the Orchestra on the Hill in Ipswich, Massachusetts, where his melody will weave with new compositions written to honor his story.

Lullabies, Arn believes, are a universal thread. Whether sung in Cambodia, Europe, or America, they carry the same promise: you are safe, you are not alone. Playing one now is his way of building bridges between cultures, of proving that even after tragedy, beauty can still connect us all.

The Ripple Effect of a Single Note

Arn often says: “Saving one life through music can ripple outward to transform society.” His own life is the proof. From a boy spared in a killing camp to a man rebuilding Cambodia’s artistic heritage, his story shows how a single flute can change the course of history.

And when young musicians like Reilly Miner — an oboist from Massachusetts who has found his own strength in music despite hardship — carry that message forward, the circle widens. Every note becomes an act of resilience. Every melody becomes a spark of hope.

The Breath of Life

The flute, at its essence, is breath turned into sound. In the killing fields, it gave a boy the will to live. In concert halls, it has become his way of speaking the unspeakable. And in Cambodia today, it carries the voices of a people who almost lost their music forever.

Arn Chorn-Pond’s story, alongside those of other survivors like Alice Herz-Sommer, reminds us that music is not just art — it is survival, memory, and healing. One flute, one hand raised, one melody can carry life through the silence.

The concert will be held at 7 p.m. on Friday, September 26 at First Church in Ipswich, MA at 1 Meetinghouse Green. Admission is free, but seating is limited. To reserve your spot, register through the Orchestra’s website: www.theorchestraonthehill.org.