Simple or not simple – that is the question

Gyula, Czeloth-Csetényi: You chose the flute as the instrument through which you would explore and experience music. What drew you to this particular instrument? Was there a defining experience that inspired you to pursue a path as a flautist?

Anne Pustlauk: I didn’t choose the flute on my own. My mother enrolled me in music school when I was ten. I was supposed to learn the recorder, but during the first meeting, my teacher said that I had good lips for the flute, so she gave me a flute instead.

Would I have chosen a different instrument? Maybe, maybe not. It took me a few years to decide to become a professional flutist. I even wanted to stop playing around age 12 or 13, but thanks to my parents, who forced me to continue, I got over it and learned to love it. There wasn’t a specific moment when I decided to become a professional musician. This idea was rather a product of different elements.

For example, I remember hearing Rampal play the Prokofiev sonata on the radio, which made me wish to play like him. I also remember being fascinated by Galway’s performance of Mercadante’s concerto at the Philharmonie in Berlin. I had a very good, though strict, flute teacher who demanded discipline and also let me play chamber music, which I greatly enjoyed. Finally, my parents and grandparents always encouraged and supported me in everything I did. I owe my career to them.

GCC: After mastering the modern Boehm flute, what inspired you to delve into the so called simple system flutes and repertoire of the 18th and 19th centuries?

A.P: During my Boehm flute studies in Karlsruhe, I had the option of choosing the baroque flute as a minor subject. I immediately liked the instrument and the repertoire. The more I delved into the world of historical performance practice, the less appealing a “normal” orchestra job seemed to me. I felt that I could broaden my horizons and learn new things.

So, I went to Brussels to study the baroque flute with Barthold Kuijken. I knew him from his recordings, which I adored, and we had met at a masterclass earlier. When I started my new studies, I left my Boehm flute in the drawer and focused 100% on the baroque flute.

Studying Early Music has a very different approach: besides learning to play the instrument, you also research its historical background. Reading historical sources became my daily bread. I began to ask myself why I play music the way I do and what I can learn from our musical ancestors. Of course, historical performance practice does not stop with the death of J.S. Bach. I was curious about how the flute and its performance practice developed after the Baroque period.

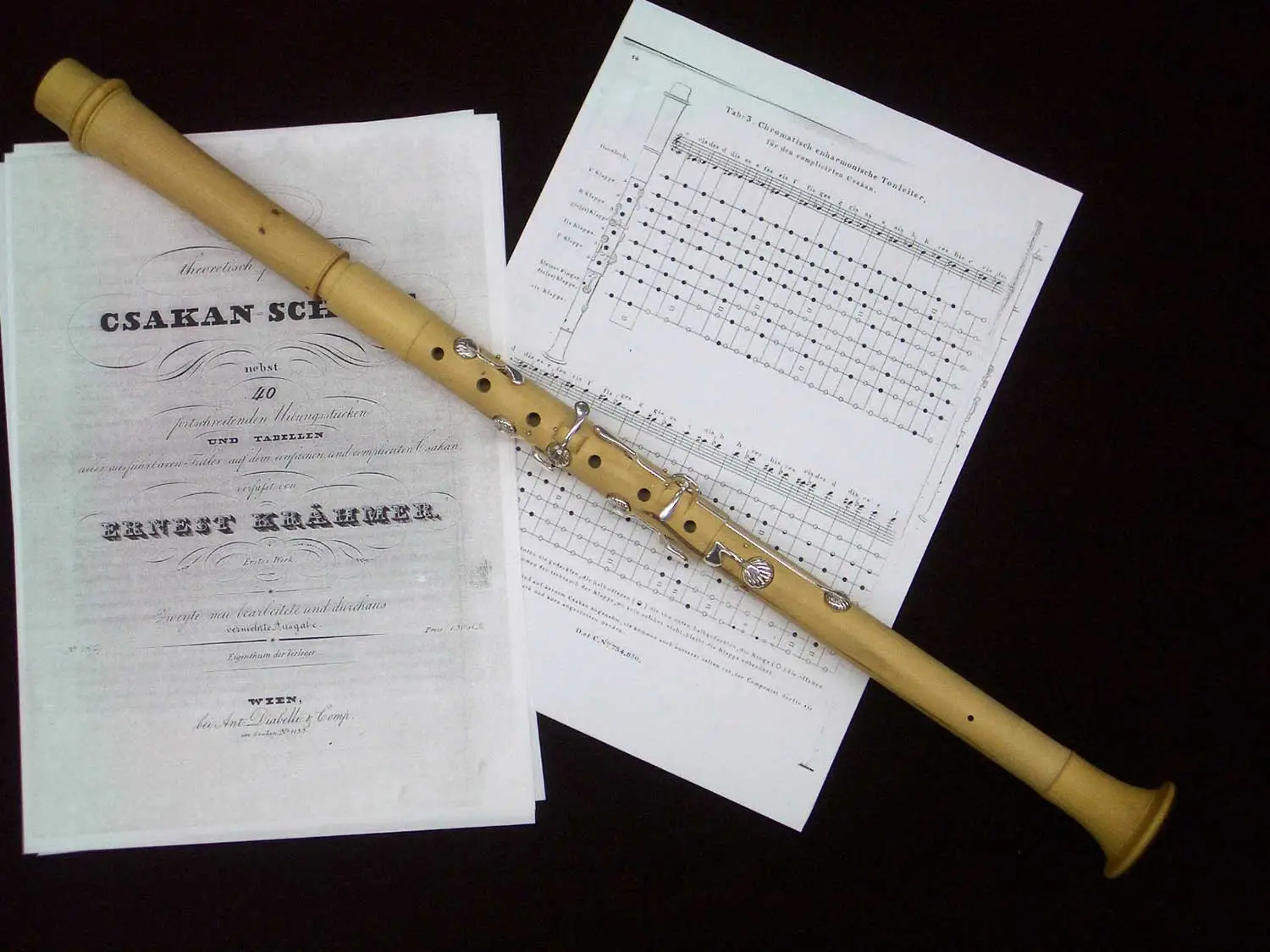

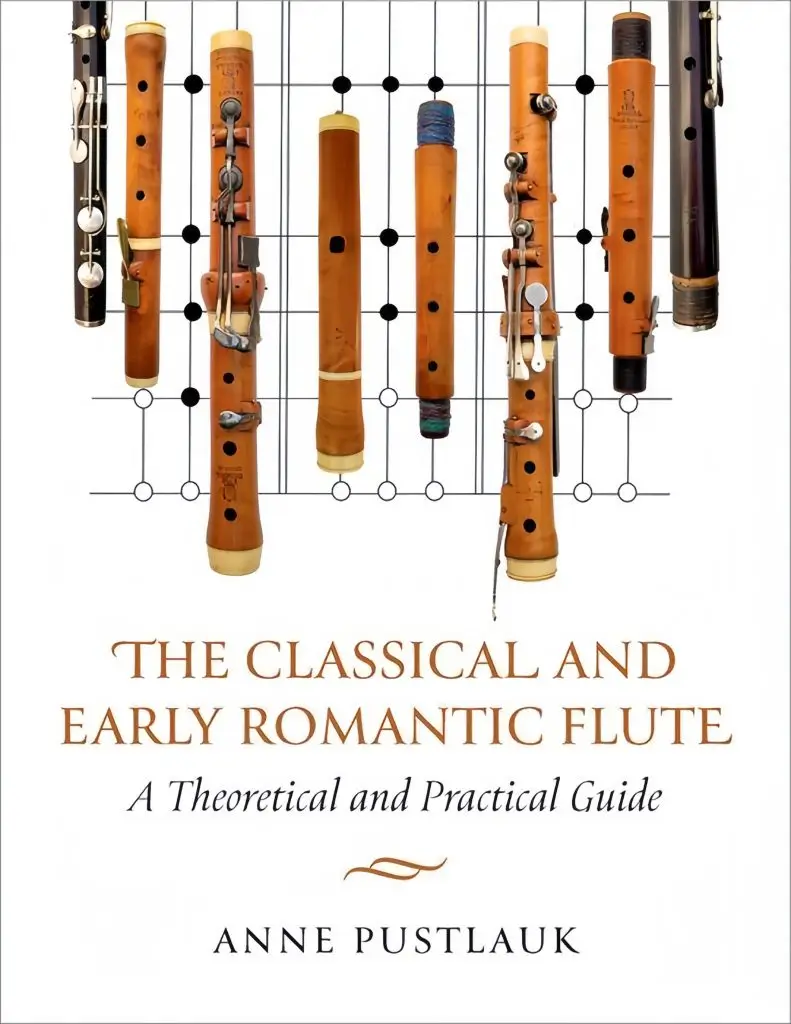

I quickly realized that serious research in this area had yet to be conducted, so I did my Ph.D. on the simple system flute, a conical flute with two or more keys that open or close one tone hole. Dealing with historical sources enables me to add another dimension to my performance. Even after many years of research, I continue to gain new insights and learn a lot. Consequently, I adapt and refine my style. For me, this is the best motivator for continuing what I do.

–> Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy, flute-solo version by C.G. Belcke (c. 1830). Played on a copy of a keyed flute by W. Liebel, made by F. Aurin.

GCC: This summer you were a guest of Budapest at the invitation of Benedek Csalog. During your summer masterclass it became evident how thoroughly and meticulously you approach musical and technical challenges. Would you say your teaching method reflects the way you yourself first engaged with simple system flutes of varying key configurations?

AP: I would say that my teaching method has developed from my own flute training and my experience with the simple system flute. I have learned which efficient practice strategies help me to play the instrument at a very high level. The simple system flute is technically very challenging because of its key system and the many alternative fingerings. If I don’t pay attention to the details while practicing, I will find it very difficult to reach that level. Posture and relaxed finger movement, for example, are very important aspects that are easy to forget when learning a new instrument. That’s why I pay close attention to these things with my students.

On a musical level, however, there are other challenges. Musical rules have changed over the centuries, and so scores can be read and interpreted differently depending on the period. Since we were educated in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it is incredibly difficult for us to deviate from their musical rules. I am thinking here of using no vibrato, playing very high leading tones, or playing rhythms in a different way due to the musical accent or tempo rubato.

I had to constantly question my musical taste and push my boundaries. In my lessons, I want the students to push their musical boundaries, too. It takes courage and perseverance, but it’s worth it! It makes our musical language more diverse and, in my opinion, the sometimes seemingly simple flute music gains in quality.

GCC: What would be your most important advice for those who want to approach simple system flutes as modern flute players?

AP: My advice would be to start simple. If you have a simple system flute at home, check what model it is. Is it a copy of a classical eight-keyed flute, or is it an original from a later period?

Choose the appropriate flute method and check its fingering charts depending on the instrument you play. German models require different fingerings than French flutes; the same is true for earlier and later flutes. Fortunately, the flute was an extremely popular instrument in the late 18th and 19th centuries, so many flute methods were published. You will find an index of the most important methods in my book.

Once you have found a suitable method, read it, play the exercises, and get used to the new fingerings. Play with relaxed hands and fingers, and avoid unnecessary tension.

GCC: Your last project focusing on the works of Jean-Louis Tulou is particularly intriguing. In this series — also on YouTube — you perform the Grands Solos written for the exams at the Paris Conservatoire. (It is accessible via the link Paris Concours on your webpage.) How did this initiative come about?

AP: Years ago, I recorded Tulou’s 13th Grand Solo, a piece that I like very much. After the recording, I wondered how many other Grands Solos Tulou had written and if they were as good as the 13th. So, I started researching. I quickly discovered that Tulou had composed 15 Grands Solos, all of which were written for the final exam at the Paris Conservatoire. He actually composed more than the Solos for the exam – 20 pieces in total – and they were all written for the simple system flute.

Jean-Louis Tulou: 13e Grand Solo, op. 96. Anne Pustlauk, Flûte à clés (Tulou, ca. 1840, collection Claire Genewein), Toby Sermeus, Piano (Pleyel, 1854). Recorded: July 2021.

It seemed like a nice project to record all these pieces using different original flutes. Thanks to a subsidy from the Flemish government, I was able to carry out this project. I borrowed most of the 21 original flutes from private collectors and the Klingendes Museum in Bern, Switzerland.

Preparing for the recording project was very intense. First, I practiced all the pieces on my own flutes. Original flutes cannot be played for very long, so I had to carefully prepare them in a short amount of time. It was a big challenge because each flute required a specific approach. Sometimes, I had to use other fingerings to achieve the desired sound or intonation. The pieces are also technically and musically challenging. However, I’m quite proud of the result! On my website, you can find not only the recordings, but also background information about the students who performed the pieces for their final exams, the instruments I used, and the pieces themselves.

GCC: Is there a particular piece or composer from the Romantic era that resonates deeply with you?

AP: I like many composers, but Kuhlau is one of my favorites. I liked his music already when I studied the Boehm flute. After reading his biography, I liked him and his compositions even more. He must have been a kind, beloved, and modest person. In my opinion, his compositions reflect that character. His quick movements are never a show-off. And I love his slow movements!

GCC: In your view, how does the musical and technical language of the Baroque period differ from that of the Early Romantic era when it comes to flute performance?

AP: Oh, I could write a book about that! The shortest answer I can give you is that baroque music speaks and early romantic music sings. For example, the Allemande from Bach’s Partita doesn’t contain any slurs. Instead, you enjoy the variety of articulation in the small and big intervals and in the important and unimportant beats of the bar. In the 19th century, flutists would have added many slurs, as well as dynamics. The small embouchure hole of the Baroque flute invites you to use different consonants and “speak” the music. This is far less evident with later flutes.

Another significant difference is the use of colors. During the Baroque period, color was a general idea: The flute sound should resemble an alto voice; the low register should be full and sonorous, and the high register should be light and sweet. In the 19th century, flutists began using alternative fingerings to produce different tone colors on individual notes. This is possible with a simple system flute due to its specific key system, but not as much with a baroque or Boehm flute.

The ability to produce different colors with alternative fingerings on a simple system flute explains why the Boehm flute, on which only one fingering was used per note, was neglected by many flutists.

GCC: As we near the end of our conversation, please share a few words about your forthcoming book (The Classical and Early Romantic Flute: A Theoretical and Practical Guide) — one that the entire flute community is eagerly anticipating!

AP: My book is already out! (The Classical and Early Romantic Flute — Oxford University Press) This book is the culmination of fifteen years of research. I studied around 160 historical flute methods, hundreds of flute works, original instruments, and countless other sources from the period between 1760 and 1850. One of the aims of this research was to find out more about how music from that period was played. I studied all the aspects necessary for performing flute music in a historically informed and inspired manner.

Imagine you want to play a concert with Romantic music for flute and string trio. First of all, you need to find good pieces. You won’t find a work catalogue in the book, but my flute database includes one with not only the titles – including around 140 for flute quartet with strings – but also comments on their quality.

If you play on historical flutes, you need to know which instruments are suitable for the pieces. Finally, you need to study aspects such as articulation, fingerings, phrasing, the meaning of Italian terms and musical signs, ornamentation and tempo flexibility, in order to understand how the music was played at the time. All these topics and many more are covered in my book.

GCC: Publishing a scholarly book is a considerable undertaking. What future plans or aspirations do you have beyond this milestone?

AP: Currently, I am researching flute education in 19th-century Belgium. You can find some Belgian works on our YouTube channel (https://www.youtube.com/@hippinmusic).

In April, I recorded flute concertos by Peter Benoit, Ferdinand Langer, and Carl Reinecke. The CD will be released in February (https://noteone-records.com/en/2025/11/05/romantic-flute-concertos/).

These projects have inspired me to delve deeper into the performance practice of the late 19th century. The development of the flute during this period is fascinating. This is not so much due to the Boehm flute, which slowly spread across Europe, but rather because of the many other types of flutes which were created alongside it. Many of these and their players have been forgotten today. Furthermore, little is known about the late-19th-century flute repertoire. I’m sure there is still much to discover!

GCC: Thank you for your answers and congratulations for your book!

About Anne Pustlauk

Anne Pustlauk discovered her passion for the transverse flute while studying with Prof. Renate Greiss-Armin in Karlsruhe. Her dedication to historical performance practice led her to the Royal Conservatory in Brussels, where she completed her bachelor’s and master’s degrees under the guidance of Barthold Kuijken and Frank Theuns.

After immersing herself in the music of the 18th century, she turned her attention to the simple system flute and, in 2011, began a Doctoral Research Program at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the KCB, supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). Her dissertation, defended in 2016, focused on the flute and its performance practice in the early 19th century.

Alongside her scholarly work, Anne remains active as a soloist, chamber musician, and orchestral player. She is widely recognized for her engaging masterclasses and presentations, where she shares her deep knowledge of historical flutes with enthusiasm and clarity.

Further Exploration

– Book: The Classical and Early Romantic Flute

– Videos: Anne Pustlauk & Hippin Music

– Website: Official page of Anne Pustlauk

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi

www.czeloth.com | ORDER BOOK “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration“

Mr. Czeloth-Csetényi, Gyula plays the flute since his age of 10. He went to the Bartók Conservatory, then he studied at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. After the demolition of the iron curtain he was the first to visit Sir James Galway’s Seminar from Hungary in Switzerland between 1993 and 1995. He was Dr. Jochen Gartner’s student at the Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich.

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi has made his first CD recording of Gamal Abdel-Rahim’s compositions there. He graduated “Cum Laude” in 1997 at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. Between 1990 and 1999 he has been the editor and publicist of the journal of the Hungarian Flute Association. Beside his classic repertoire he plays at a jazz band where his own compositions are performed, too. He played together with recognized jazz musicians.

As classical flutist he has performed all over Europe and in Japan. He made a solo CD in 2001, its title is “12 Romance”. He is a co-lead author of the book under title – “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration”. The book was published in 2022.