This article on expression in music is the second in a series of articles published in the Flute Almanac. The first article was published in The Babel Flute, September 20, 2022. The articles are all excerpted from the book, “Interpretation and Expression: A Workbook for Musicians” by Tim Lane©. Paper Route Press, 2020.

Expression is Air in Motion

When we exhale through the flute we hope to transform our expressive intentions into sounds that will be heard by others. The technical and expressive mastery of air as it flows through the flute is a lifelong endeavor. Paul Taffanel (1844 -1908) wrote that,

The breath is the soul of the flute, and the culminating point in the art of playing. The disciplined breath must be a docile agent, now supple, now powerful, which the the flutist should be able to govern with the same dexterity as which a violinist wields their bow. It is the motion force behind the sound and the spirit that animates it, gives it voice and the spirit that animates it, gives it life and becomes a voice capable of expressing all of the emotions.

Methode Complete de Flute, par Taffanel & Gaubert. Alphonse Leduc ed 1958. p. 185. Maurice Sharp & Legato Playing

When I was in high school my flute teacher, Maurice Sharp, announced one day that he was going to teach me about a critical aspect of expressive playing which he referred to as “legato playing”. For Mr. Sharp, legato playing was about how the flute player’s air stream had to be used when creating an expressive shape or phrase structure. Rather than simply meaning the use of slurs to connect notes, it was a measure of the “directional clarity” achieved when shaping multiple-note phrases. Interestingly, the Latin word root of legato is legare which means “to bind”, so legato playing can be defined as the binding together of groups of notes in order to clarify and express phrase structures. In practice, I find that shaping a motion while sounding a single note serves as a model for shaping that same motion while sounding multiple notes.

Why Legato Playing is Difficult

Legato playing (the binding of notes) is difficult because our exhaling air “flow” is simultaneously used for 1. expressive shaping and for 2. sound production work (which creates the platform for expressive shaping). Adding to this difficulty is the fact that expressive shaping is meant to be recognized, while sound production “work” is not. In other words, the directional clarity of a phrase is not to be encumbered or compromised by sound production difficulties (i.e., wide leaps, reversed note directions, difficult rhythms, dynamic changes, articulation patterns, or fast passage work etc.).

For example, legato playing is easier to achieve when the expressive demands and sound production demands made on the air stream compliment each other (the two demands require the same types of air flow changes). This is the case when playing an approaching phrase of stepwise, rising notes; the air flow has to be increased for both expressive and note production purposes.

This is also the case in the excerpt from “June” included on the following page.

In contrast, legato playing is more difficult to achieve when the expressive demands and the sound production demands made on the air stream do not complement each other (the two demands require “oppositional” air flow changes). This is the case when playing a receding phrase of stepwise, rising notes; the air flow has to be decreased for expressive purposes while, at the same time, it needs to be increased for note production purposes.

For the sake of practice and to reinforce this point, reverse the first approaching and receding arch in the excerpt from “June” and play it as a receding and approaching arch.

Recognizing the inevitable contradictions and difficulties that arise due to the dual use of a single air stream creates a “window to look through” when problem solving when addressing problematic passage work.

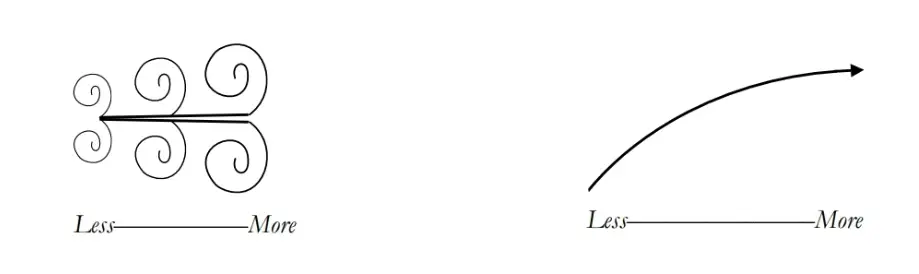

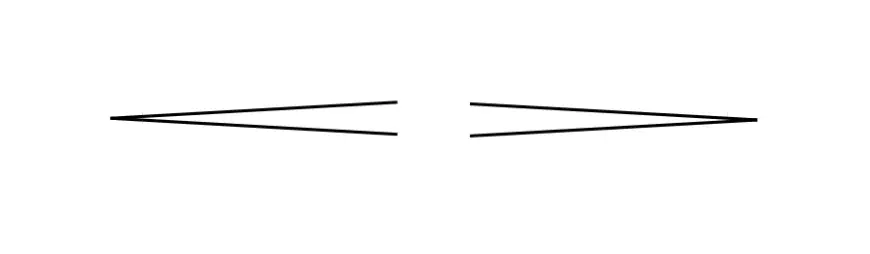

Creating Approaching, Receding, and Holding Motions

Each motion has a unique set of beginning, middle, and ending characteristics.

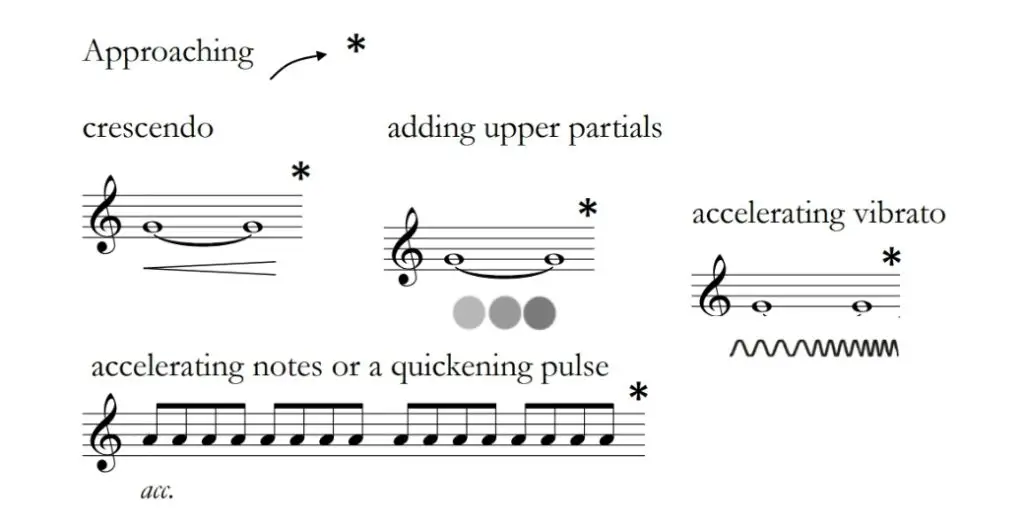

Approaching motions begin with “less” energy and end with “more” energy.

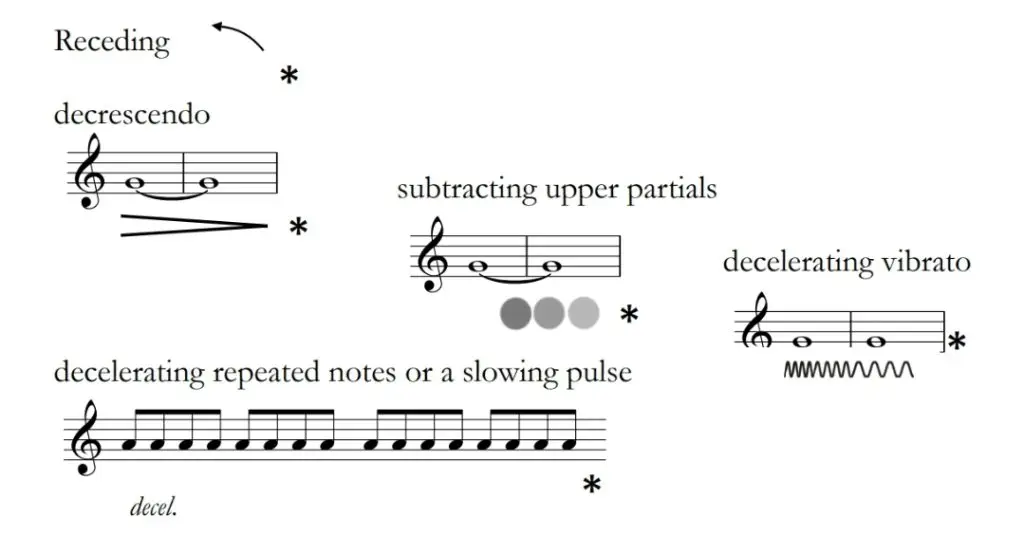

Receding motions begin with “more” energy and end with “less” energy.

Holding motions maintain a constant energy level. They are shaped by the absence of sound-changes.

The following excerpt, taken from “June” by Peter Tchaikovsky, includes pairs of Approaching and Receding motions that form arches.

Approaching and Receding Changes Sound(s)

Volume levels, partial content, aural clarity, the rate of vibrato, and the pulse can all increase with approaching motions. Oppositely, volume, partial content, aural clarity, the rate of vibrato and pulse can all decrease with receding motions.

The Techniques of Sound Change

Changes in dynamics are caused by changing the volume of exhaled air.

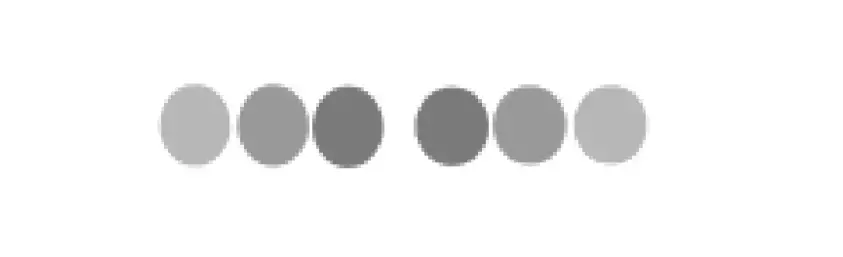

Changing the partial content of a tone is caused by changing the air speed/air pressure. This is accomplished by changing the size of the lip aperture and/or by changing the air volume.

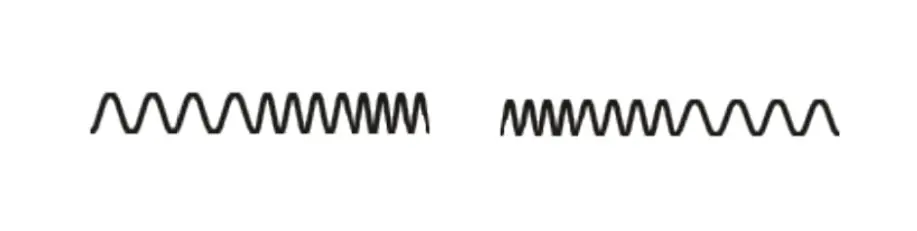

Vibrato is caused by oscillating changes in air volume.

A Holding motion maintains a constant level of energy. They are shaped by using a constant amount of air volume as you exhale.

Changing Elements of Sound as a Whole

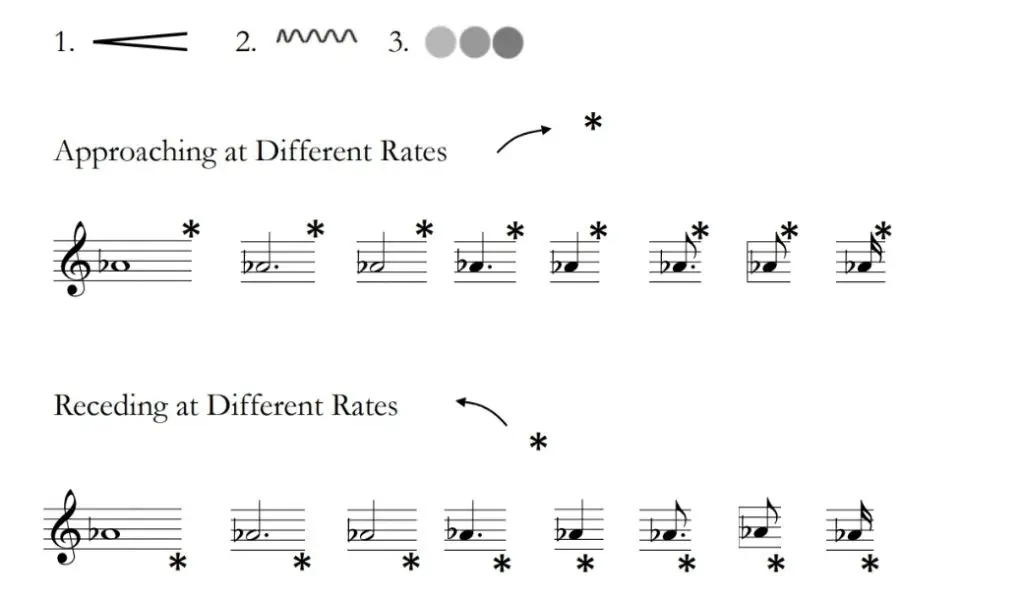

The energetic changes that take place when creating Approaching and Receding shapes all reinforce the impression that spatial changes are taking place. The following Shaping Studies are presented so that players can work not only on shaping the trajectory of an air wave, but also on how the presentation of the air wave might be varied.

Shaping I

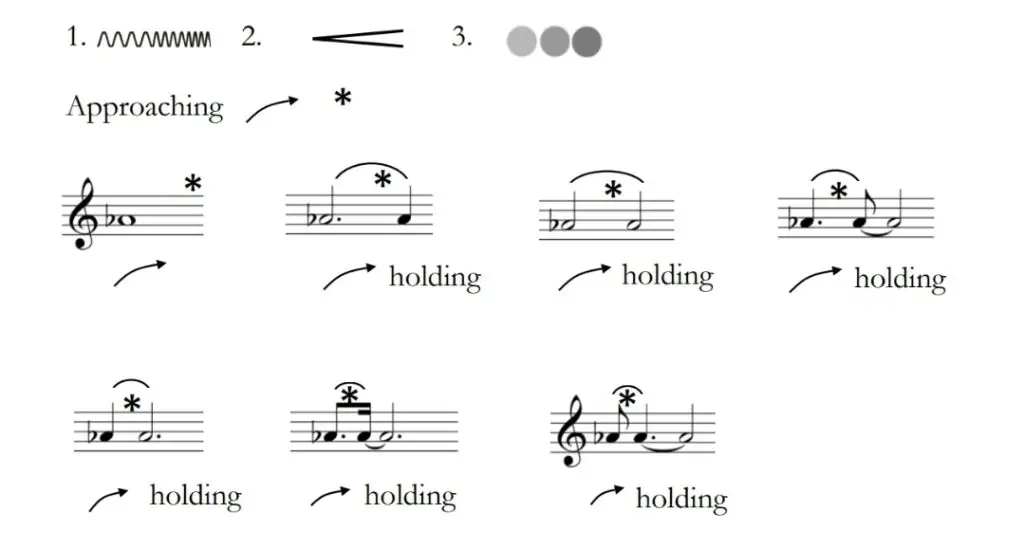

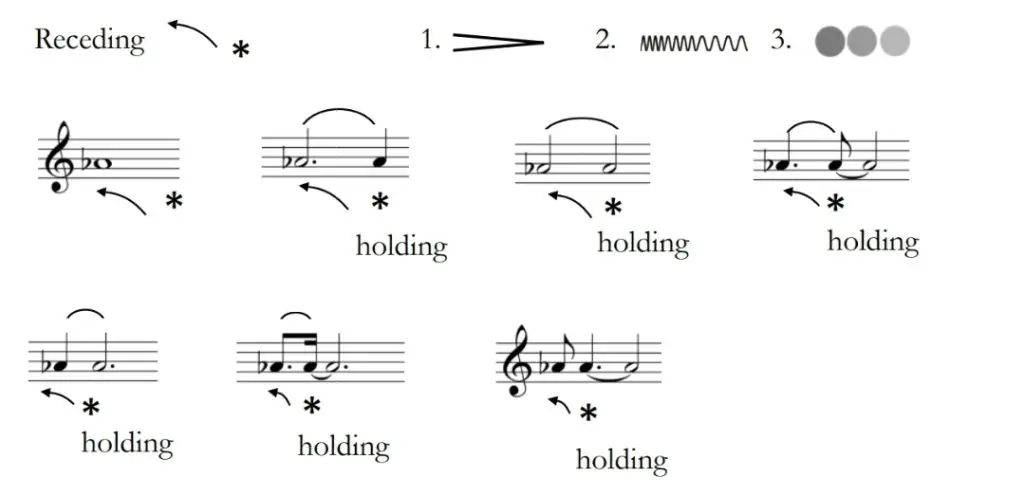

As you work on shaping, try to emphasize the indicated sound-change element more than the other ones (without necessarily excluding them).

The destination of an approach is indicated by an asterisk placed above the staff.

The destination of a receding motion is indicated by an asterisk placed below the staff.

In Context

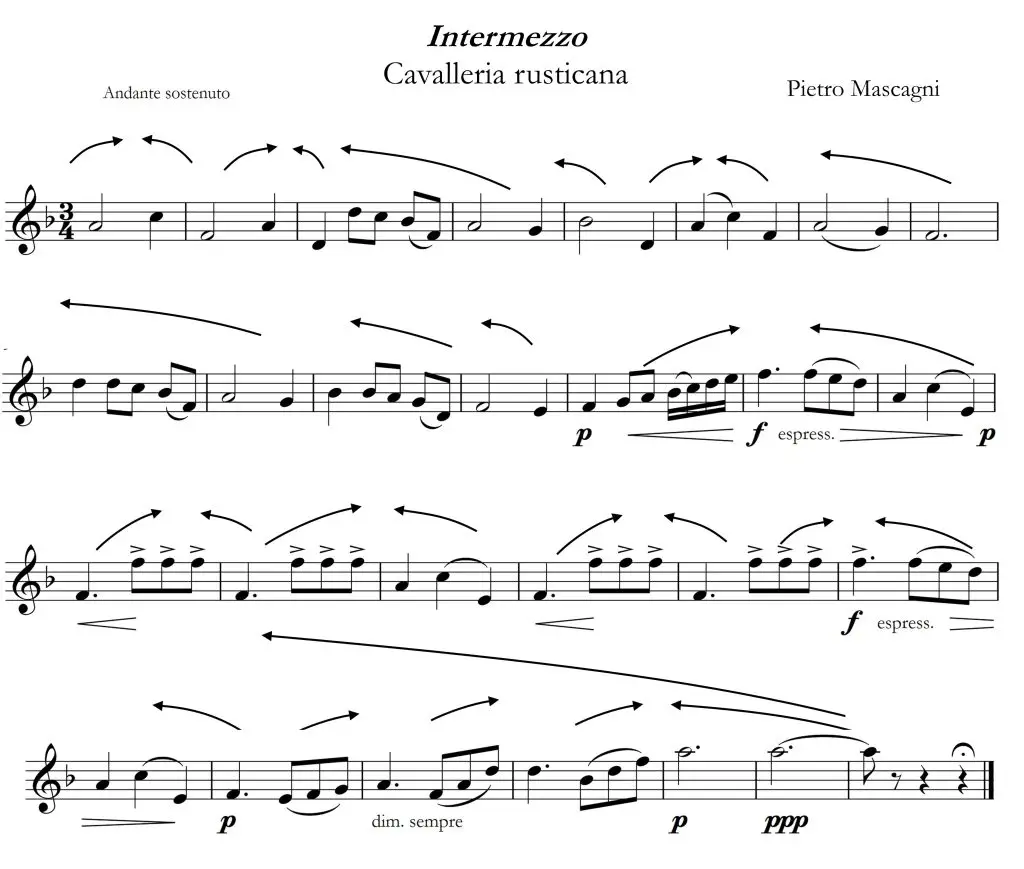

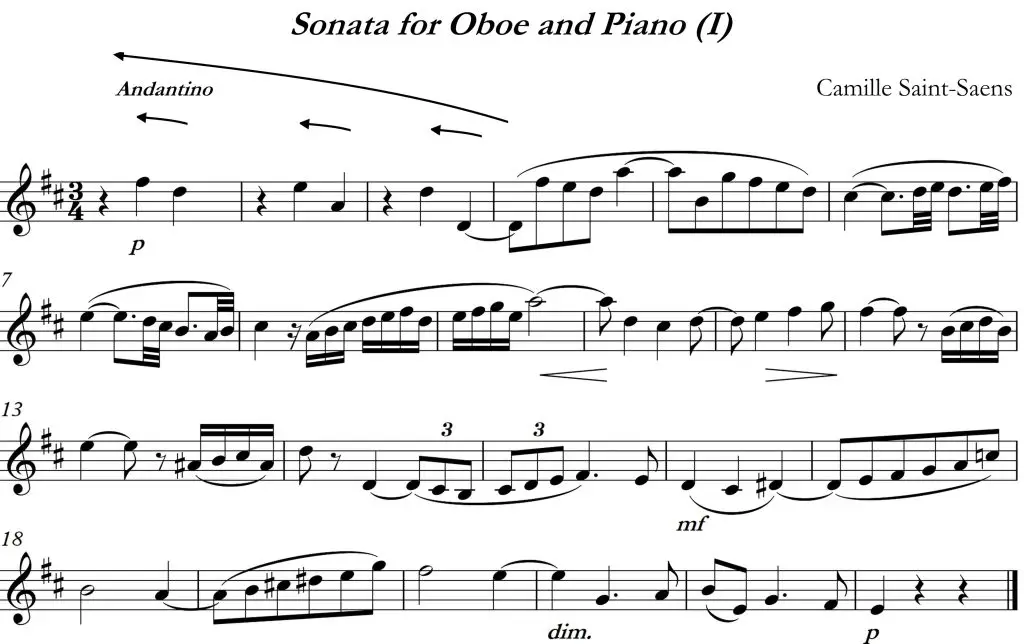

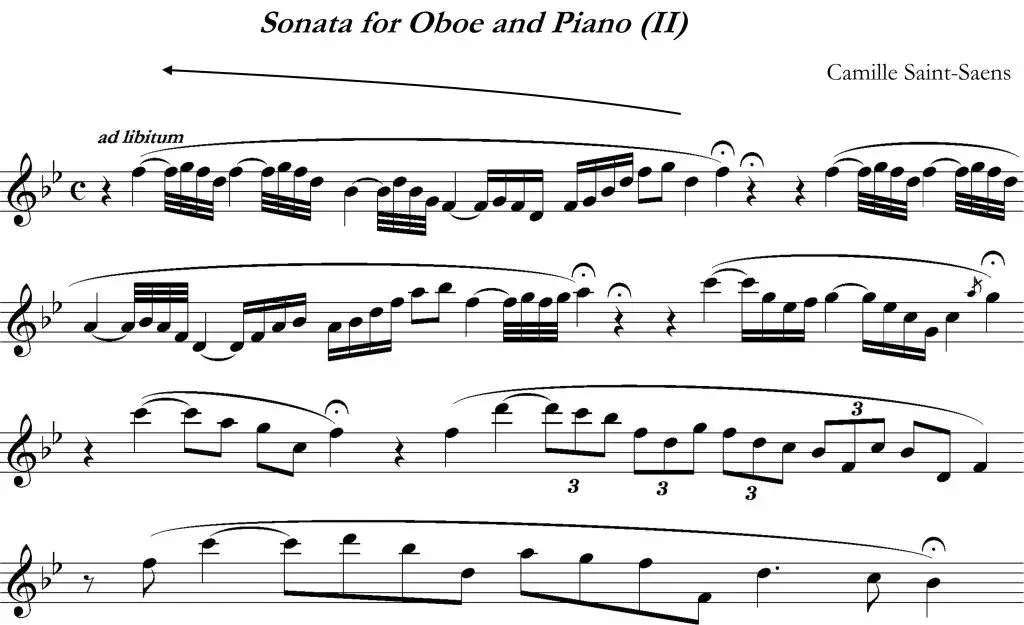

Practice applying the three sound-changes and quickening or slowing the pulse to varying degrees as you read through the following excerpts. The composition of the motions and their placement within the larger structure will influence your decisions about which change-elements to emphasize more than the others and to what degree. You will also note that multiple motions of varying durations can take place simultaneously; smaller motions can be shaped “within” or “inside” the time frame that it takes to shape a larger motion.

Shaping II

Shaping occurs at differing rates. In the examples below, reading left to right, the rate of each sound change increases as the note values are shortened. You can also shape the motions reading from right to left.

Emphasize any number or combination of the following sound changes.

In Context

Return to the any or all of the three excerpts on the previous two pages and little by little increase the tempo. This can be likened to speeding up a film so that all of the same motions take place within a shorter time frame.

Shaping III

In this shaping exercise the rates of the motions quicken as in the previous exercise, however, once the motion has been completed the note is sustained without any changes to create a “hold”.

Practice the examples emphasizing any number or combination of the following sound changes.

In Context

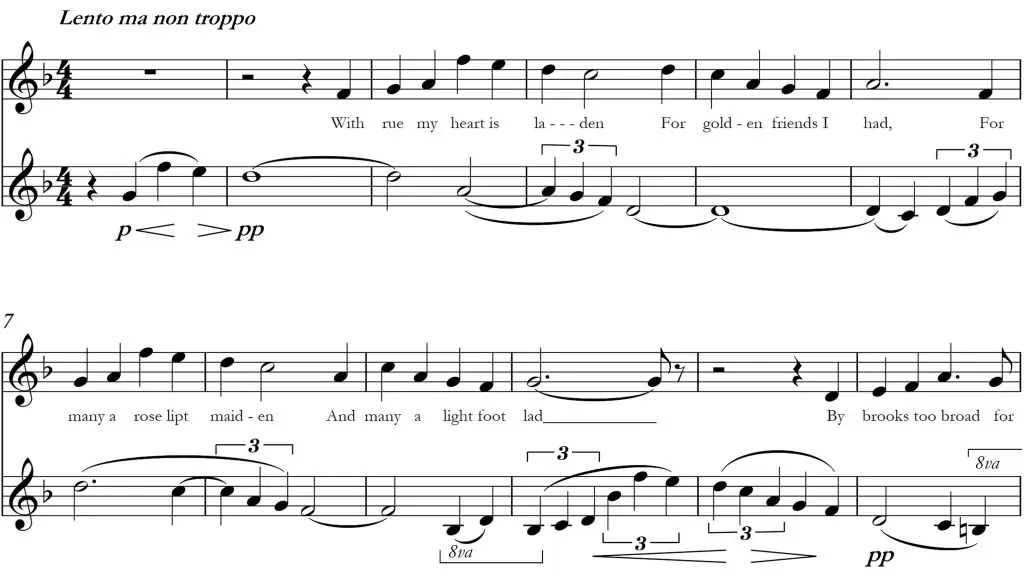

Excerpted from the second movement of the Johann N. Hummel Concerto for Trumpet.

Shaping III continued…

In Context

Excerpted from, “With rue my heart is laden” by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

To be continued in the following magazine issues

Tim Lane

Paper Route Press

Tim Lane is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire where he taught from 1989 – 2020. Prior to that he was a faculty member at Eastern Illinois University, the Interlochen Arts Camp, and the Cleveland Institute of Music Preparatory Department. He has been a member of the Orquestra Sinfonica de Veracruz, Mexico, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Ohio Chamber Orchestra, and the Eau Claire Chamber Orchestra. He currently serves as the principal flute player with the Chippewa Valley Symphony Orchestra and operates “Paper Route Press” which specializes in unique and innovative flute-related publications. Mr. Lane attended high school at the Interlochen Arts Academy and earned his Bachelor of Music from Cleveland Institute of Music. He later earned his Masters and Doctoral Degrees from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. As a college-age student he studied the flute with Maurice Sharp, Harold Bennett, Alexander Murray, and Claude Monteux.