The development of mechanical flutists represents a fascinating chapter in the history of both music and robotics. These automata, crafted with precision and ingenuity, captured the imagination of audiences across Europe and demonstrated the potential of early mechanical engineering to replicate human artistry. This review goes deeper into the lives of the inventors and the intricate details of their remarkable creations, many of which laid the foundation for modern robotics.

Ismail Al-Jazari: Pioneering Robotics and Music Automation in the 12th Century

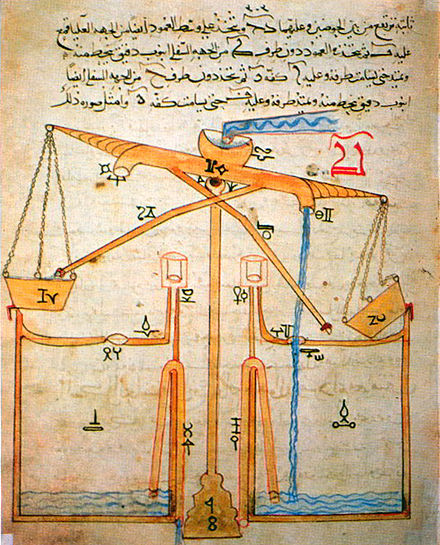

Ismail Al-Jazari, often hailed as the “father of robotics,” was a polymath born in 1136 in what is now Turkey. A scholar, inventor, mechanical engineer, mathematician, and artisan, Al-Jazari compiled his groundbreaking ideas in The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, detailing 100 inventions with precise instructions and illustrations.

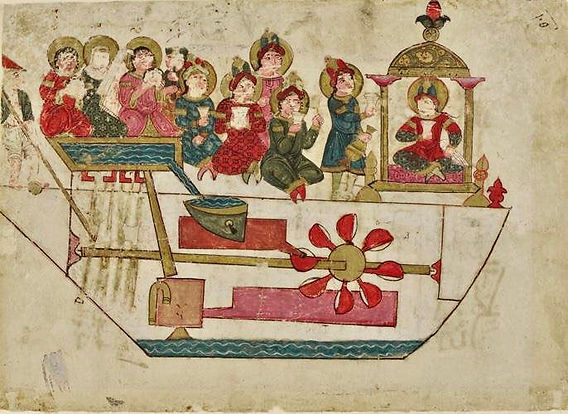

Among his most intricate creations was a band of four hydro-powered musical robots, designed to float on a lake and entertain guests at royal celebrations. Notably, Al-Jazari’s robot drummer featured movable pegs to set the rhythm, making this invention one of the earliest examples of programmable automatons.

Functioning like a music box, this invention took the form of a boat decorated with four “musicians” – a harpist, a flautist, and two drummers – who performed songs to entertain guests.

Jacques de Vaucanson’s Mechanical Flutist (1737)

Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782) was a French inventor and engineer known for his groundbreaking work in automata. Vaucanson was born in Grenoble, France, into a family of glove makers. From an early age, he displayed a strong interest in mechanics and clockwork. He pursued his education in a Jesuit school and later studied anatomy and mechanical arts, which heavily influenced his future inventions.

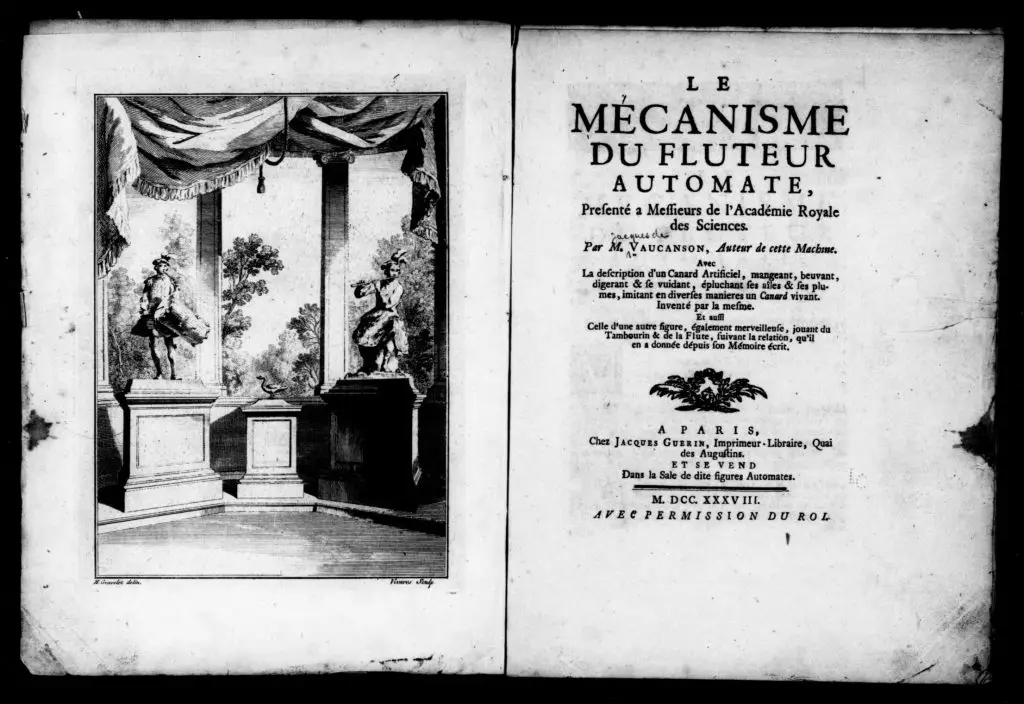

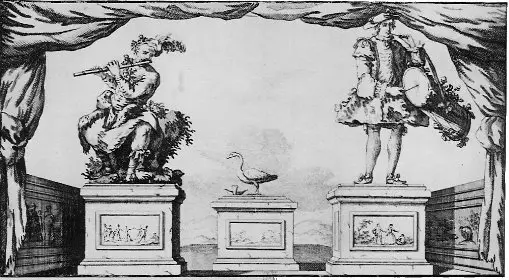

In 1737, Vaucanson unveiled his Mechanical Flutist, a life-sized automaton capable of playing a real flute. The automaton was revolutionary because it simulated not only finger movements but also the intricate breath control required to play the instrument.

Using bellows and a system of pipes, Vaucanson’s automaton produced airflow, allowing the flutist to play twelve different melodies.

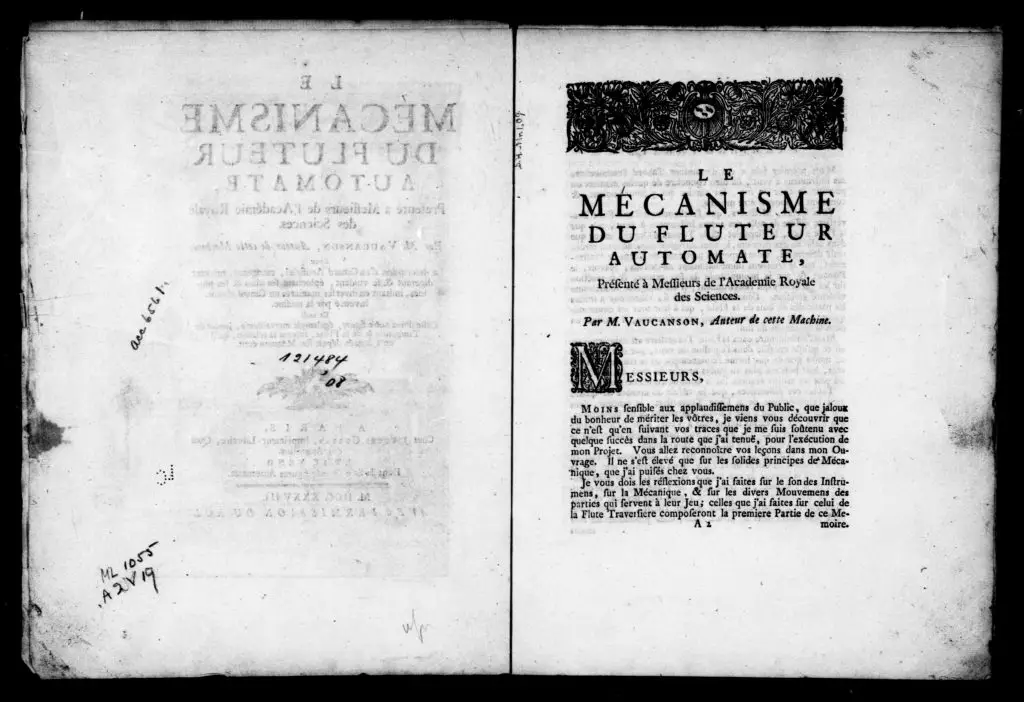

Details of the Flutist’s Mechanism The Mechanical Flutist used windpipes and hidden bellows to blow air into the flute, mimicking the respiratory actions of a human player. The automaton’s lips and fingers moved in coordination, controlled by a complex system of cams, levers, and rods.

The invention was so precise that it even simulated the subtle articulation and dynamics that a human flutist would produce. This level of sophistication was unheard of at the time, making Vaucanson’s work a major technological leap.

Vaucanson’s Mechanical Flutist was an extraordinary creation featuring intricate mechanical elements that mimicked the human anatomy. The automaton’s lips could change shape and move in and out, while a mechanical tongue regulated the flow of air. To further control the sound, it was equipped with three sets of bellows, each providing different levels of air pressure to allow for dynamic expression. These features enabled the flutist to play with a degree of precision that rivaled many human musicians.

More than just a musical automaton, the Flutist was considered one of the first androids – a mechanical human capable of sophisticated tasks, in this case, playing the flute better than many real performers. When it was unveiled to the public, it became a major attraction, with spectators willing to pay a significant portion of their income just to see the automaton perform its repertoire of twelve songs.

The French Academy of Sciences was so intrigued that they visited the automaton, and Vaucanson documented the workings of his invention in a detailed account titled Le Mécanisme du fluteur automate, which he presented to the Academy in 1738.

Johann Joachim Quantz, the renowned composer, court musician and flute instructor to Frederick II of Prussia, critiqued Jacques de Vaucanson’s Mechanical Flutist for its technical limitations. Specifically, Quantz noted that the automaton’s inability to adequately move its lips led to the need for increased wind pressure to play in the upper octaves. This, he argued, resulted in a harsh, unpleasant tone, far from the refined sound desired in real flute performance. Quantz cautioned against using such methods in human playing due to their detrimental effect on tone quality.

While mechanical automata were a popular trend in Europe during that era, often viewed as sophisticated toys, Vaucanson’s creations stood out for their lifelike mechanical precision and complexity, earning them a reputation as revolutionary in the field of engineering and music.

Legacy and Survival

Vaucanson’s automaton was displayed across Europe, drawing enormous crowds and inspiring future generations of engineers. Unfortunately, the original automaton did not survive. However, its legacy persisted, influencing not only automaton makers but also the early development of robotics. In the 20th century, replicas of Vaucanson’s flutist were created, offering modern audiences a glimpse into this incredible piece of mechanical artistry.

Innocenzo Manzetti’s Automaton Flutist (1849)

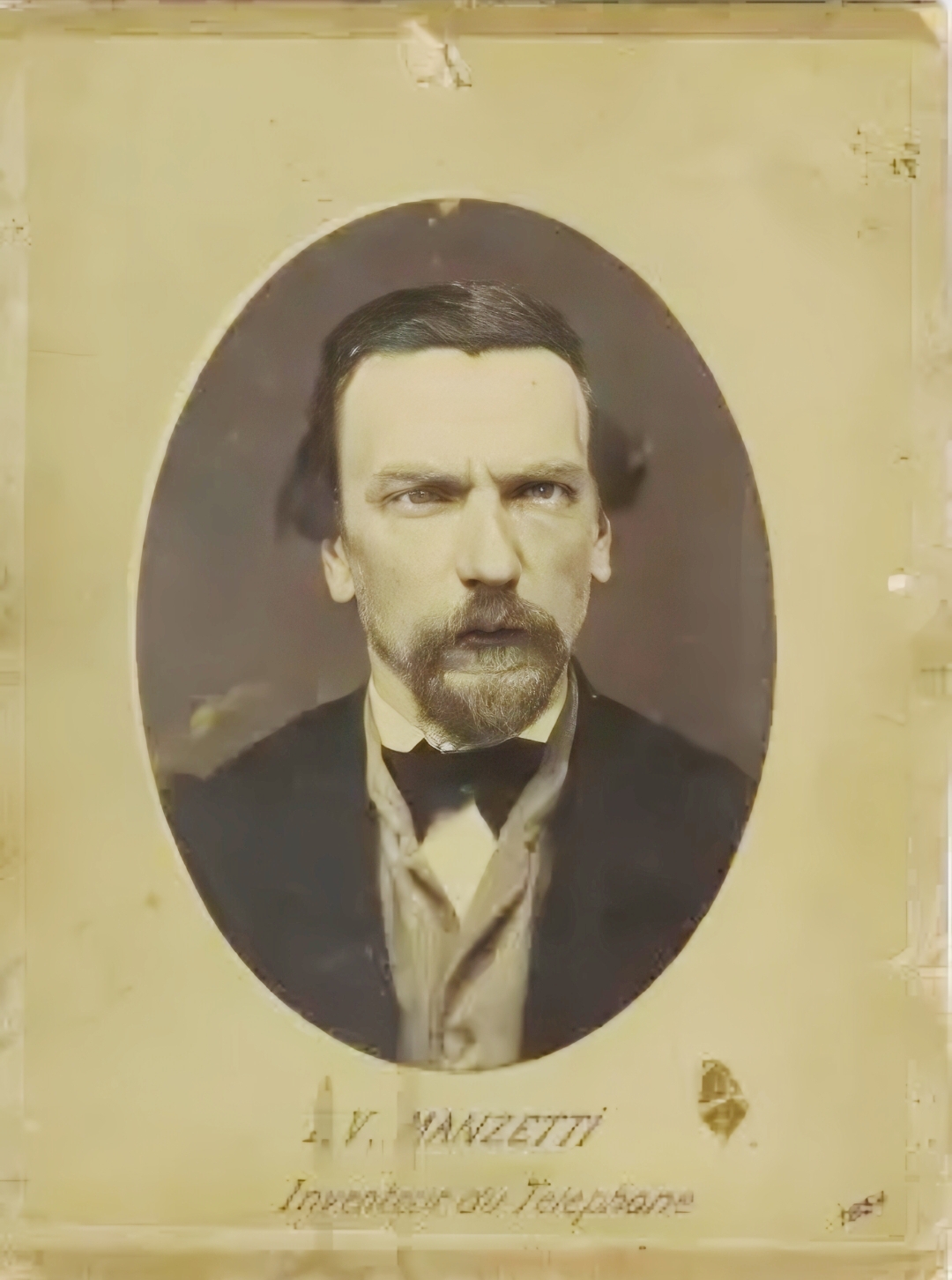

Innocenzo Manzetti (1826–1877), born in Aosta, Italy, was an Italian polymath known for his wide-ranging inventions, which included early prototypes of the telephone, steam-powered cars, and his famous Automaton Flutist. Despite his brilliance, Manzetti lived a relatively obscure life, overshadowed by more prominent inventors of his era.

Manzetti showed an aptitude for mechanics from a young age, excelling in both science and mathematics at the Jesuit-run Collège Saint-Bénin in Aosta. His inventive spirit led him to create numerous devices throughout his life, ranging from hydraulic machines to musical automatons. Financial constraints, however, hindered his ability to patent many of his inventions, which ultimately limited his recognition.

The Automaton Flutist’s Intricate Mechanism In 1849, at the age of 24, Manzetti completed his Automaton Flutist. This life-sized figure was seated in a chair and played a flute using a complex system of compressed air and mechanical fingers. Like Vaucanson’s creation, Manzetti’s flutist could perform a set repertoire of musical pieces. The automaton’s inner workings consisted of hidden levers, rods, and tubes that controlled the lips and fingers, which operated the flute keys with precision.

What set Manzetti’s flutist apart was his later innovation, which allowed the automaton to play more complex music alongside an organ. This innovation enabled an organist to play while the automaton’s flute mimicked the keyboard’s notes, creating a synchronized performance between man and machine.

Sadly, the Automaton Flutist did not survive. After Manzetti’s death in 1877, the automaton’s whereabouts became unknown, with some speculating that it was dismantled or destroyed. Nevertheless, Manzetti’s work remains a key chapter in the history of automatons, and his genius is slowly being rediscovered today.

Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s Automaton Musicians (1770s)

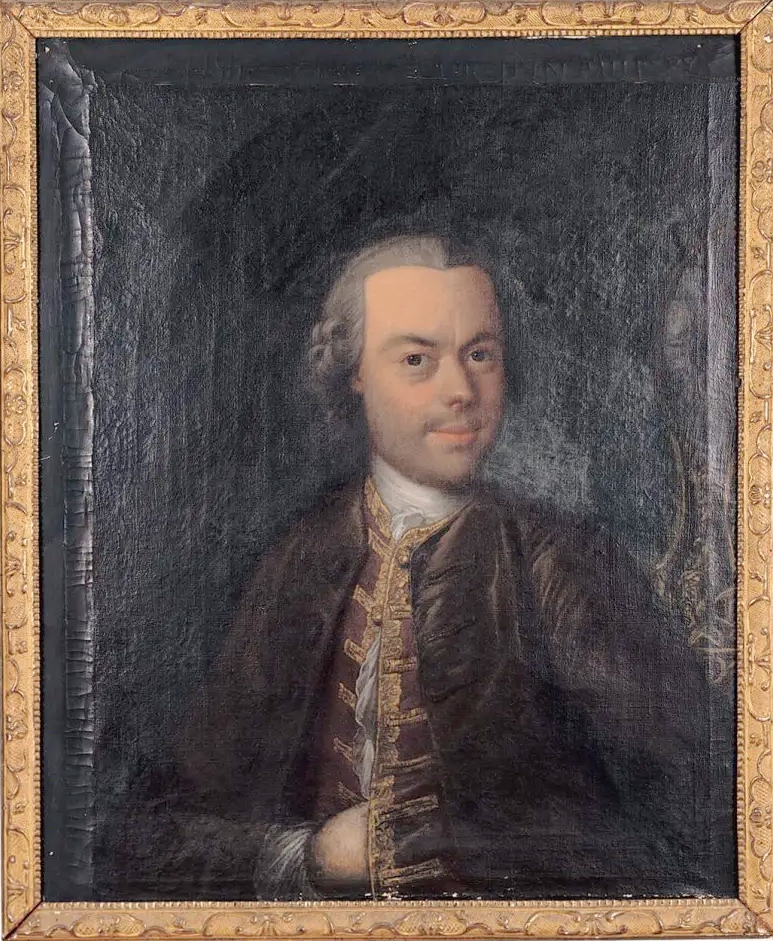

Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721–1790), a Swiss watchmaker, is known for creating some of the most intricate and sophisticated automata ever made. Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, Jaquet-Droz was trained as a watchmaker but quickly expanded his expertise into the realm of automaton-making.

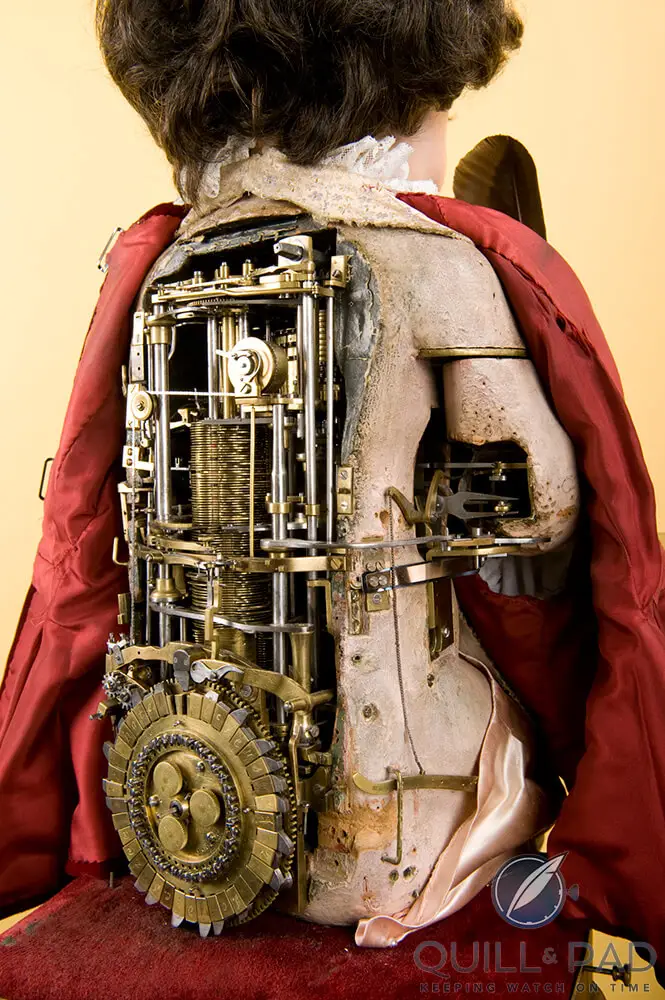

Among his creations were The Writer, The Draughtsman, and The Musician. The Musician, while not a flutist, deserves mention because it could play a miniature organ and execute five different melodies. Jaquet-Droz’s automata were admired for their lifelike movements, with The Musician being able to breathe, move its head, and blink its eyes while playing.

Remarkably, many of Jaquet-Droz’s creations have survived and are housed in the Neuchâtel Museum of Art and History in Switzerland. These automata are still functional and continue to be displayed, offering modern audiences a glimpse into 18th-century engineering brilliance.

Friedrich Kaufmann’s Mechanical Orchestra (1800s)

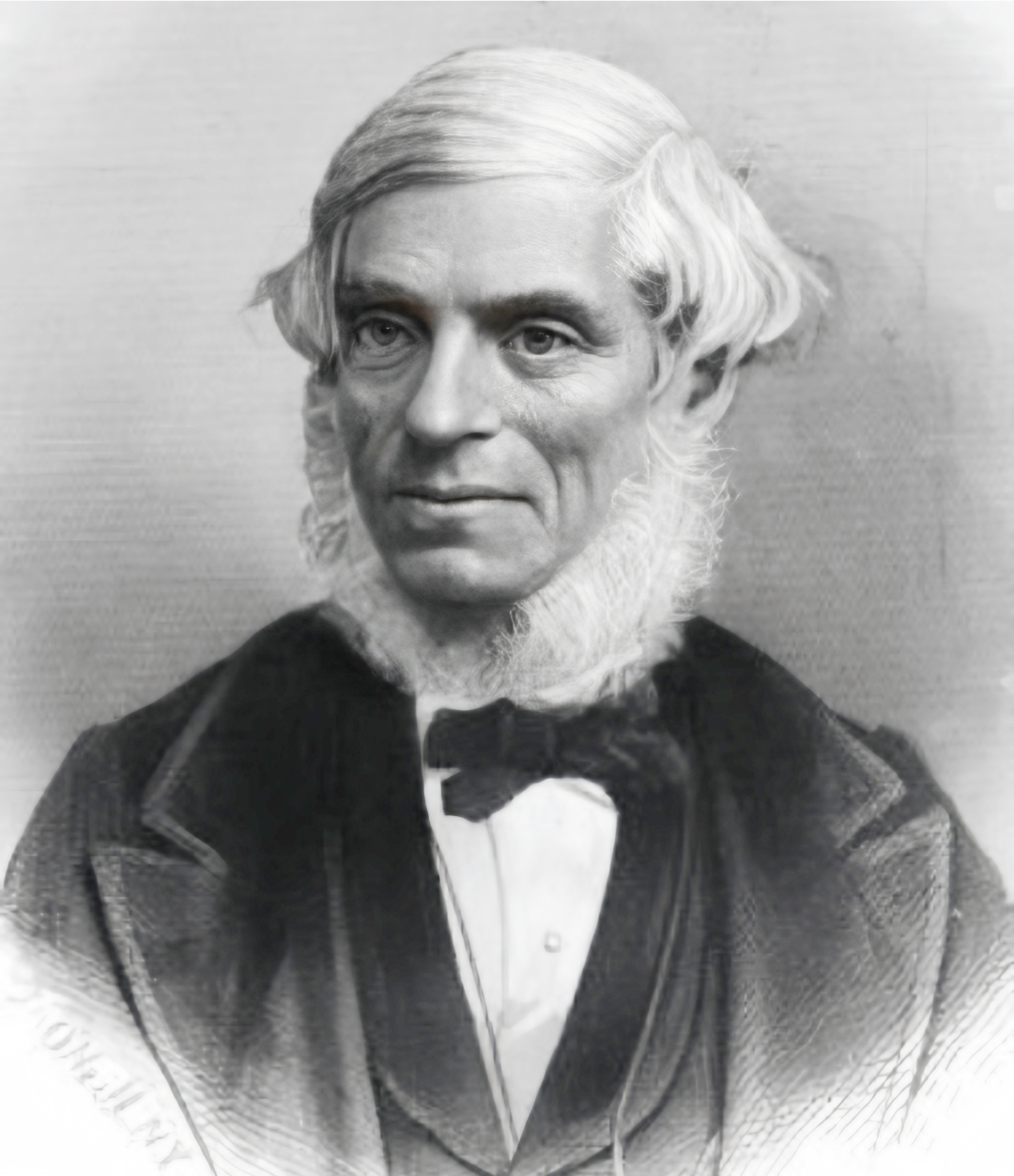

Friedrich Kaufmann (1785–1866) was a German inventor who contributed significantly to the development of mechanical music. Born in Dresden, Kaufmann belonged to a family of instrument makers and engineers. His most notable creations included a range of mechanical instruments that could perform in an orchestra-like ensemble, including flute-playing automatons.

Kaufmann’s automatons were simpler than those of Vaucanson or Jaquet-Droz, but they were still marvels of engineering for their time. His Mechanical Orchestra could play pre-programmed tunes, entertaining audiences at public exhibitions and fairs.

Kaufmann’s automata did not survive into the modern era, but his work laid the foundation for future developments in automated musical instruments, such as player pianos and orchestrions. His contributions to mechanical music remain influential in the history of automatons.

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (or Mälzel): Inventor of the Mechanical Trumpeter and Beethoven’s Collaborator (1800s)

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (1772 – 1838) was an innovative German inventor and showman whose fascination with mechanical devices led to remarkable creations that bridged technology and music. In 1804, Maelzel invented the Panharmonicon, an automated device capable of playing all the instruments of a military band. Powered by bellows and controlled by rotating cylinders that stored the notes, it drew widespread attention and garnered the admiration of Ludwig van Beethoven and other renowned composers.. The invention made Maelzel famous across Europe, leading to his appointment as imperial court mechanician in Vienna.

Around 1806 Maelzel focused on building an automaton trumpeter. This mechanical figure, with realistic movements and quick costume changes, could play both French and Austrian field signals and military tunes.

In 1808, he invented an enhanced ear trumpet and a musical chronometer. He also improved the metronome, an invention that profoundly influenced musicianship. Maelzel’s metronome allowed composers and performers to communicate tempo precisely, which appealed to composers like Beethoven.

The two initially collaborated on projects that combined Maelzel’s inventions with Beethoven’s music. One notable work was Wellington’s Victory, a composition celebrating a British military victory over France. This piece was designed for the Panharmonicon and performed to enthusiastic audiences, enhancing both Beethoven’s and Maelzel’s reputations.

However, their relationship grew tense over issues of ownership and profit-sharing. Maelzel attempted to commercialize the work outside of Beethoven’s influence, leading to a public dispute. Beethoven accused Maelzel of fraud and unauthorized usage, which culminated in Beethoven seeking legal action to assert his rights.

Despite these conflicts, the two eventually reconciled, with Beethoven recognizing the value of Maelzel’s metronome. He even adopted it for marking precise tempos in his compositions, which was groundbreaking for the time. Maelzel’s innovations and marketing savvy helped elevate his own status, while Beethoven’s work with him underscored the ways technology and art could converge. Their story remains a testament to the creative and sometimes contentious dynamic between inventors and artists in the early 19th century.

Modern Reconstructions and the Legacy of Mechanical Musicians

While many of these early mechanical flutists and musicians no longer exist, efforts to reconstruct and study them have continued in modern times. Replicas of Vaucanson’s and Jaquet-Droz’s automata have been created, allowing modern engineers to understand the intricacies of their designs. These reconstructions serve as a testament to the ingenuity of early inventors and their ability to push the boundaries of what was technologically possible.

The legacy of mechanical musicians lives on in modern robotics, where machines continue to play music, often drawing inspiration from the automata of the past. The work of these early inventors has influenced everything from player pianos to contemporary robotic performances, demonstrating the enduring fascination with combining technology and artistry.

The Enduring Appeal of Mechanical Music

From Vaucanson to Manzetti, the history of mechanical flutists and musicians showcases a remarkable journey of human ingenuity. These inventors sought to replicate the complexity of human performance through the use of advanced mechanical systems, resulting in machines that not only entertained but also paved the way for modern robotics. While many of these automata are lost to history, their influence continues to inspire engineers, musicians, and artists today.

In addition to historical examples like Vaucanson’s Mechanical Flutist, modern audiences can experience a remarkable flutist automaton in the Murtogh D. Guinness Collection at the Morris Museum in New Jersey.

This flutist automaton, part of the museum’s permanent exhibition Musical Machines & Living Dolls, showcases the lifelike mechanical movements that have fascinated viewers for centuries. The automaton plays a flute, simulating human breath control and finger movements, just as its historical predecessors did. Preserved alongside other mechanical marvels, this flutist continues to bridge the gap between artistry and engineering, offering a glimpse into the evolution of automated musicianship.

Their legacy reminds us that the desire to blend technology and art is not a modern phenomenon—it is a tradition that stretches back centuries, reflecting humanity’s enduring curiosity and creativity.

Yulia Berry

Yulia Berry is the founder of Flute Almanac, The Babel Flute, and the New England Flute Institute. A highly experienced flutist and mentor, she holds a Doctor of Music Arts degree from the Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (Russia).

Renowned for her virtuosity and expressive playing, she has performed as a soloist and chamber musician worldwide. An expert in flute pedagogy, she is known for her innovative teaching methods that emphasize technique, musicality, and artistry.

She has written extensively on the flute’s connection to art, culture, and history across different eras.

Большое спасибо за статью, Юлия!!! Как всегда очень интересный, познавательный и оригинальный материал!