There is an historically based case for interpreting Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s D-Major Flute Concerto with an increased degree of expressive variety in comparison to what is currently practiced. If forgotten stylistic features that are present in the historical record were to be re-introduced into performances, a greater sense of expressive contrast would be brought to life. The result would be a more integrated and intermingled account of the Galant and Classical styles when performing the concerto.

Historical research can be an important source of musical learning, especially when notions of authenticity do not overshadow one’s curiosity and musical intuition. Well-founded historical scholarship can uncover new avenues of understanding and considerations that, for any number of reasons, have been overlooked and/or forgotten over time. Information garnered from historical scholarship can be both a source of and a prompt for creative, musical performances.

During the Classical period the aesthetic of unity and variety was highly valued in the arts. Heinrich Christoph Koch wrote that music acquires its expressive ability through the application of the aesthetic dualism of unity and variety.

He wrote,

“It is well known that every composition, be it short or long, must have unity but also variety.” [1 – see the footnotes at the end]

According to Koch, a composition is unified through its portrayal of a particular affect that is represented by its main key and principal theme. Variety is represented through the inclusion of additional affective content, modulations, and expanded phrase structures.

During the Classical period music elements such as genre, style, key, meter, rhythmic gesture, and texture formed a common vocabulary used for affective expression. The associative qualities of these musical gestures resulted from their relationships with informal musical activities and simpler musical forms, whose social contexts and purposes were commonly known. This is like using a musical motif or gesture in order to conjure up a specific image, quality or mood in the listener’s mind. The shark motif from the movie Jaws or musical themes lifted from popular television shows and movies are good examples of this. In a very general sense, affective motifs and the keys in which they were represented were a vocabulary of references that composers could draw from in the pursuit of unity and variety.

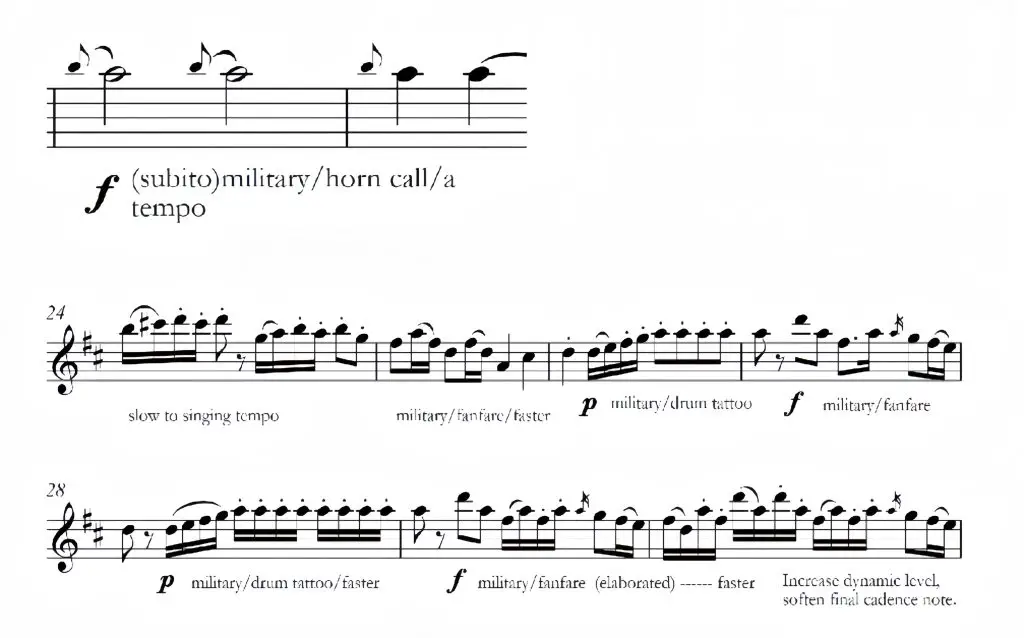

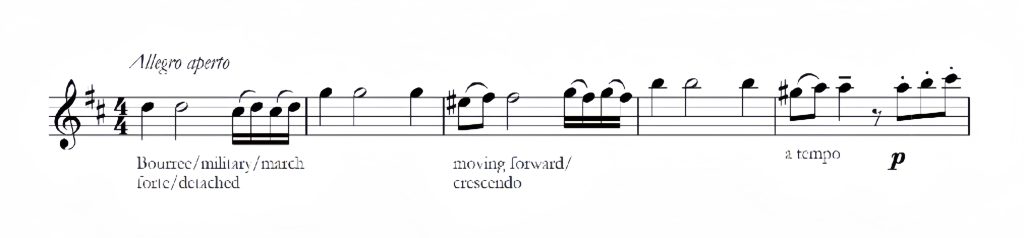

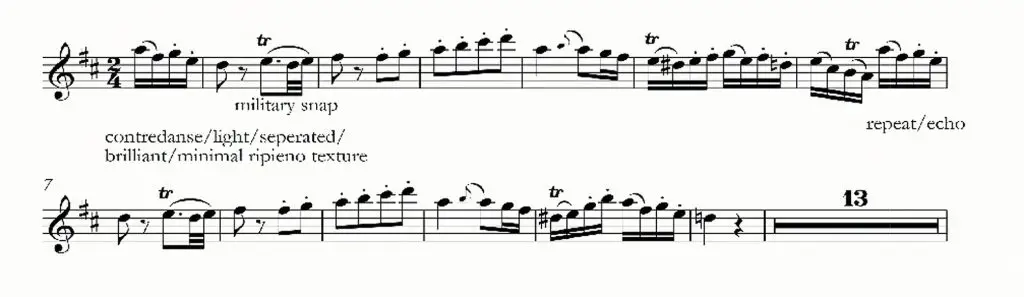

Examples of the military, singing, brilliant, dance, and learned styles can be found in Mozart’s flute concerto. The military style was often included in Baroque and Classical concertos, as this was idiomatic to instrumental writing and often consisted of arpeggiated triads, dotted rhythms, and repeating notes.

The singing style was associated with the aria; it was lyrical and included more conjunct lines, slower note values and a limited range.

The brilliant style included technical passage work and was also typically included in concertos at that time.

The Bourree dance style is represented in the first movement of the concerto. It was a relaxed dance.

The third movement of the concerto includes a contredanse. It was a light, simple dance.

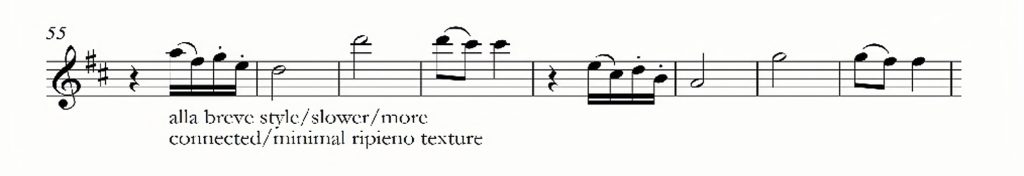

The alla breve or learned style was associated with church music and it was serious in character.

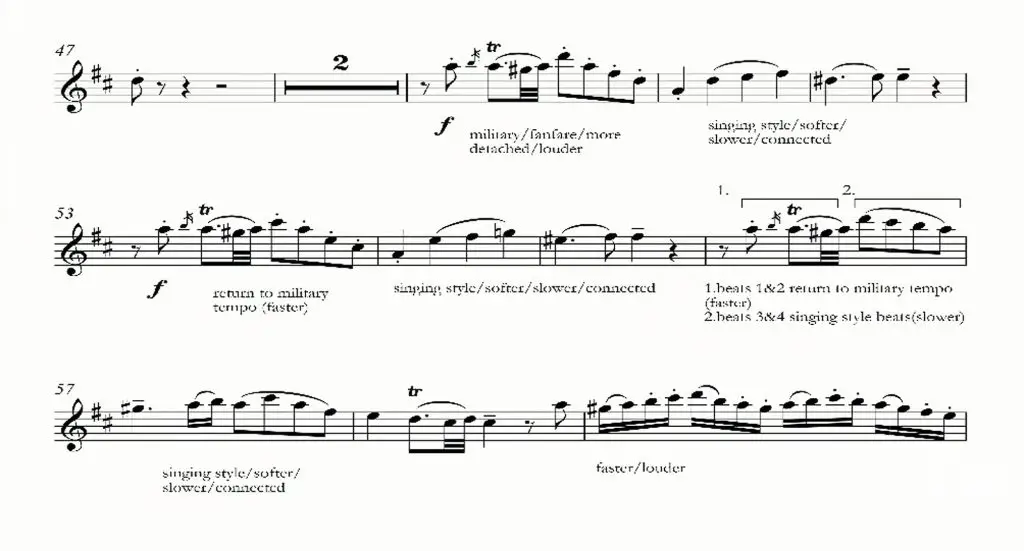

In accordance with the principle of unity and variety, the affective content that was written into compositions during the Classical period was expected to be distinguished by performers and clearly recognized by audiences. Performance techniques for doing so included adjusting tempo, dynamics, articulation, and the degree of separation between phrases. In his School of Clavier Playing, Johann Gottlieb Turk refers to a quickening or hesitating when discussing tempo changes directly related to affective changes, and he specifically states that these types of changes are not to be confused with un-intended tempo changes.

It is difficult to specify all the places where quickening and hesitating can take place… In compositions whose character is vehemence, anger, rage, fury, and the like, the most forceful passages can be performed in a somewhat hastened (accelerando) motion. Also, certain thoughts which are repeated in a more intensified manner (generally higher) require that the speed be increased to some extent.

Sometimes when gentle feelings are interrupted by a lively passage, the later can be played somewhat more rapidly. A hastening of the tempo may also take place where a vehement affect is unexpectedly aroused. For extraordinarily tender, longing or melancholy passages, in which the emotion, as it were, is concentrated.

In one point, the effect can be very much intensified by an increasing hesitation. The tempo is also taken gradually slower for tones before certain fermatas as if their powers were gradually being exhausted. The passages towards the end of a composition (or part of a composition) which are marked diminuendo, diluendo, smorzando, and the like, can also be played in a somewhat more lingering manner. [2]

Turk also notes that the tempo between conjunct musical sections with contrasting affects can be slightly altered.

A tenderly moving passage between two lively and fiery thoughts can be executed in a somewhat hesitating manner; but, in this case, the tempo is not taken gradually slower, but immediately a little slower (however, only a little.) [3]

Examples of this are evident in the first movement of the concerto between measures 50 through 58.

Dynamics also depended on the affective content of a phrase.

Compositions of a spirited, happy, lively, sublime, magnificent, proud, daring, courageous, serious, wild, and furious character all require a certain degree of loudness. This degree must even be increased or decreased according to whether the feeling or passion is represented in a more vehement or more moderate manner…

Compositions of a gentle, innocent, naïve, pleading, tender, moving, sad, melancholy and the like, character all require softer execution… [4]

The style of articulation was also related to affective content. Turk writes that there are two types of articulation and states that they relate more to note lengths than to dynamics.

The heavy or light performance adds profoundly to the expression of the ruling sentiment… the effect depends on the ways in which staccato, connection, slurring and sustaining are properly used. [5]

To avoid misunderstanding I must remark here that heavy and light refer more to the sustaining or separating of notes than to loud and soft. In certain cases, for example, in an allegro vivo, scherzando, vivace con allegrezza etc., the delivery must be rather light, but more or less strong; on the other hand, a piece with a pathetic character, for example an adagio mesto, con afflizzione etc., that need to be slurred and therefore somewhat heavy, should not be played loud. But in most cases heavy and strong do go together. [6]

Finally, the degree of separation between two phrases that include contrasting affects should be increased.

If a passage of gentle sensitivity follows a brisk and fiery thought, then both periods must likewise be more carefully separated than would be necessary if they were of the same character. [7]

The aesthetic of unity and variety was also applied in the use of harmony, phrase lengths, and cadence types. What today is called sonata form was, at the time, referred to by Koch as an expanded, two-reprise form. Koch wrote that harmony is the primary source of variety in an expanded two-part reprise form and that melody stands in close relation to the composition’s principal affect. Accordingly, non-diatonic pitch content, modulations and key changes can all be emphasized in performance.

The symmetry and regularity of phrases was important for unity, while departing from asymmetry and irregularity added variety. Koch notes that the appropriate use of asymmetrical phrase lengths can only be determined by taste and feeling. The French writer, Comte de la Cepede, wrote that while symmetrical phrases reflect the beauty of nature, composing asymmetrical phrase structures allows for a more personal expression of the passions.

The composer will be exempt from these rules (the rules of proportion), when he is carried away by the intermittent and volatile passions that he is striving to paint. Under such circumstances will not perfection merely result in frigidity? [8]

It follows that phrase parts that were added to symmetrical phrases (placed either within or at the ends of phrases) and that created asymmetrical phrase lengths could also be distinguished in performance.

In summation, the first and third movements of the concerto should be performed at a louder dynamic level, with a lighter, more separated, style of articulation in comparison to the second movement which should be both softer and of a heavier (more connected) style of articulation. Throughout the concerto the military and brilliant affects can be performed at faster tempos and with raised dynamics in comparison to the singing, imitative and alla breve affects. Both the singing style (which occurs throughout the concerto) and the alla breve style (which occurs in the third movement of the concerto) should both be performed using a heavier (more connected) style of articulation.

During the Classical period the relationship between the tutti and the solo textures was more unified and less oppositional than it is today. Koch likened the tutti texture to a chorus in a Greek tragedy that provided commentary for the material presented in the solo part. This meant that there was less contrastive variety between the two textures: the soloist often joined the initial and closing tutti sections in the three movements of the concerto and in the phrases that introduced the cadences, while the tutti alone played in the brief interjections that interrupted longer solo sections.

Historical research makes the case that more variety and expressive contrast can be brought out in today’s performances of W. A. Mozart’s D-Major Flute Concerto K 314/285d (apart from tutti and solo textures). In particular, the eighteenth-century aesthetic of unity and variety and the use of affects give credence to this conclusion. Most importantly, the chronological proximity of the Galant and Classical styles becomes more apparent in performance when this approach is taken. Re-introducing “forgotten” stylistic features from that time to today’s audiences can bring new perspectives to well-known and frequently heard compositions.

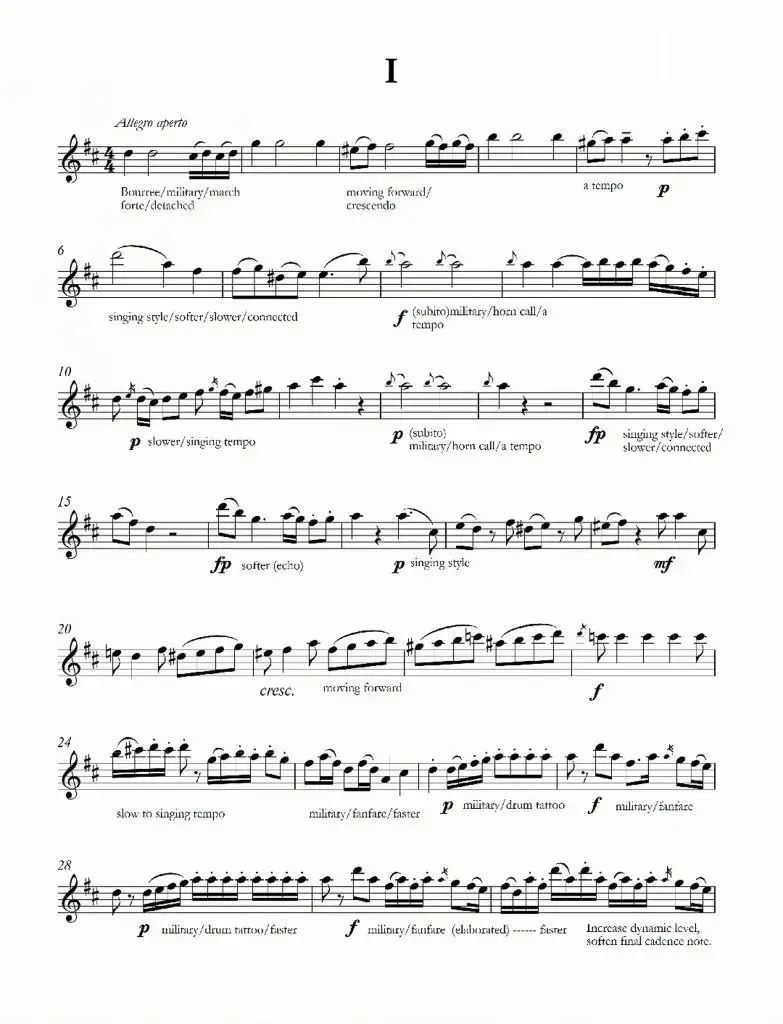

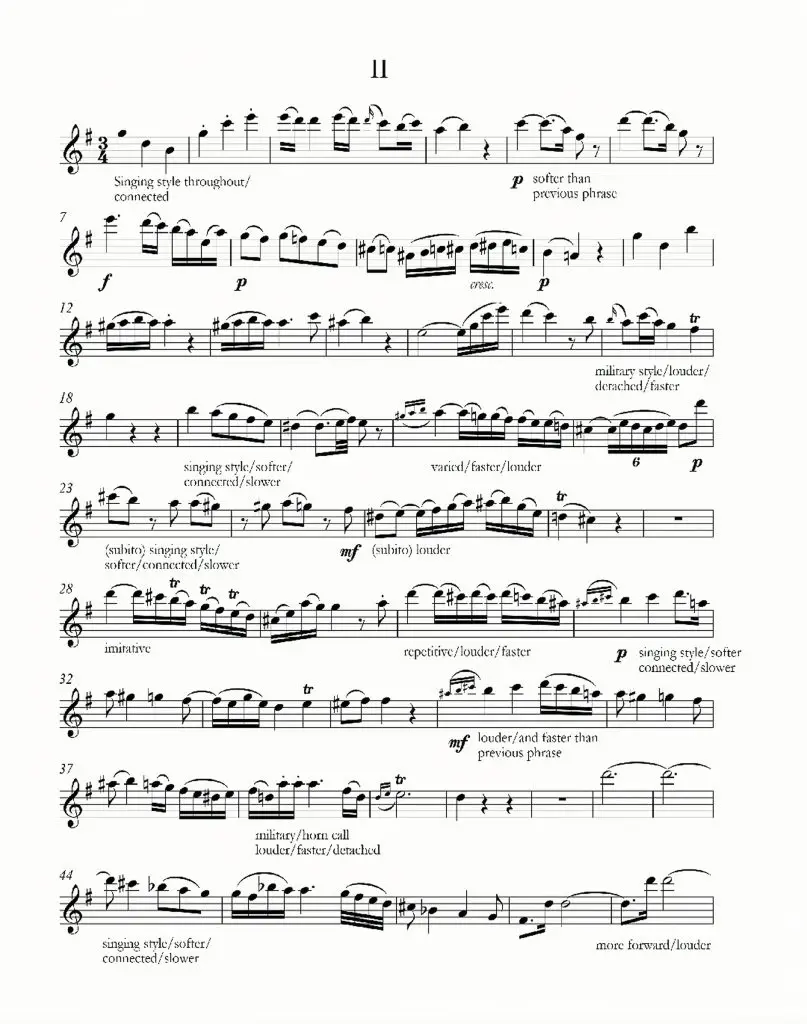

Excerpts from each movement of concerto are presented here with their affective content noted as well as the performance considerations that their presence suggests. These examples are excerpted from the Paper Route Press edition of the concerto. A complete Paper Route Press edition of the D-Major Flute Concerto K 314/285d by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart will be accessible at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) / Petrucci Music Library, as of November 1, 2024.

Footnotes

- Heinrich Christoph Koch, (1749-1816) Versuch einer Anleitung zur Composition (1782, 1787, 1793), Volume 2, (Leipzig, 1887) quoted in Nancy Kovaleff Baker, “The Aesthetic Theories of Heinrich Christoph Koch,” International Review of Aesthetics and Sociology of Music viii (1977): 82.

- Daniel Gottlieb Turk, Klavierschule (1789) republished as School of Clavier Playing, translated by Raymond H. Haggh (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), p. 330-336

- Ibid, p. 330-336.

- Ibid, p. 330-336.

- Ibid, p. 330-336.

- Ibid, p. 330-336.

- Ibid, p. 330-336.

- Bernard Germain Etienne de la Ville sur Illon, Comte de la Cepede, La Poetique de la Musique 2 volumes (Paris, 1785) quoted in Music and Aesthetics in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries, edited by Peter Huray and James Day (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 133-134.

Tim Lane

Paper Route Press

Tim Lane is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire where he taught from 1989 – 2020. Prior to that he was a faculty member at Eastern Illinois University, the Interlochen Arts Camp, and the Cleveland Institute of Music Preparatory Department.

He has been a member of the Orquestra Sinfonica de Veracruz, Mexico, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Ohio Chamber Orchestra, and the Eau Claire Chamber Orchestra. He currently serves as the principal flute player with the Chippewa Valley Symphony Orchestra and operates “Paper Route Press” which specializes in unique and innovative flute-related publications. Mr. Lane attended high school at the Interlochen Arts Academy and earned his Bachelor of Music from Cleveland Institute of Music.

He later earned his Masters and Doctoral Degrees from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. As a college-age student he studied the flute with Maurice Sharp, Harold Bennett, Alexander Murray, and Claude Monteux.