The world of music mourns the loss of Sofia Gubaidulina, one of the most remarkable composers of the 20th and 21st centuries, who passed away on March 13, 2025, at the age of 93. A composer of extraordinary depth and spiritual insight, she transformed the realm of contemporary classical music, exploring the intersections of sound, silence, and transcendence. Her influence extended far beyond the confines of any single genre, instrument, or tradition, leaving an indelible mark on modern music.

Among her many contributions, Gubaidulina’s flute compositions hold a special place, offering flutists works of great emotional and technical depth. Her approach to the instrument was far from conventional – she treated the flute not merely as a vehicle for melody but as an expressive entity capable of embodying breath, voice, and human emotion itself.

A Life Dedicated to Musical Exploration

Born in Chistopol, Tatarstan, in 1931, Gubaidulina spent much of her formative years in Kazan, where she studied at the Kazan Conservatory before continuing her education at the Moscow Conservatory.

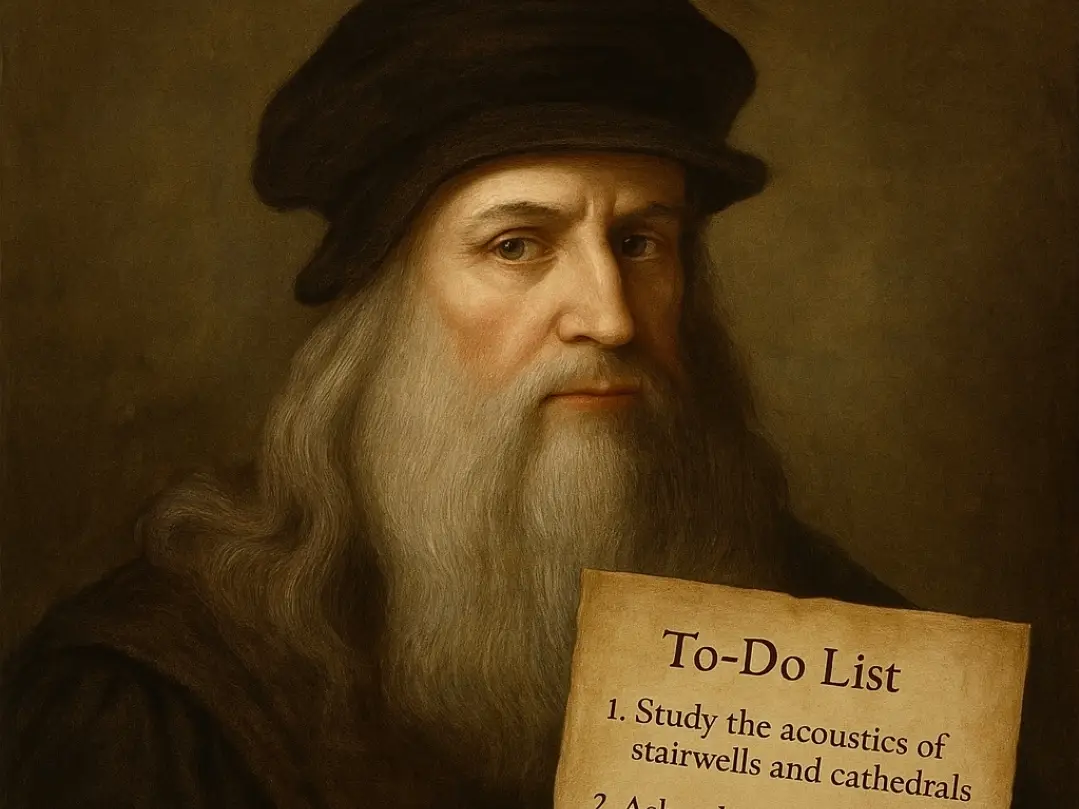

Photo: Sofia Gubaidulina Center for Contemporary Music

Despite facing significant artistic censorship in the Soviet Union – where her music was deemed too experimental – she remained steadfast in her artistic vision. It was only later, as she gained recognition in the West, that her genius was truly acknowledged. From 1991, she made Germany her home, continuing to compose and inspire musicians worldwide.

Throughout her career, she remained deeply committed to exploring the spiritual essence of sound. Her compositions frequently reflect themes of light and darkness, struggle and redemption, mortality and eternity. These philosophical concerns were not just abstract concepts but deeply embedded in the fabric of her music, particularly in her flute works.

The Flute as a Voice of the Soul

In Gubaidulina’s compositions, the flute often serves as more than just an instrument – it becomes a voice, an entity that breathes, sighs, and speaks with human-like expressivity. Scholars have noted that her approach to flute writing is deeply connected to vocal articulation, evoking the nuances of the human voice. This is particularly evident in her Sonatina for Solo Flute (1978), where she employs speech-like rhythms, expressive inflections, and melodic gestures borrowed from both Baroque and Romantic traditions.

The Sonatina, while relatively short, is a striking example of her ability to create an intimate monologue between the performer and the audience. Gubaidulina’s use of recitative-like phrases, dynamic contrasts, and intricate articulation transforms the flute into a storyteller, weaving an emotional and deeply introspective narrative. This work avoids the virtuosic brilliance often associated with Romantic flute music, instead embracing a more measured, expressive approach, drawing the listener into an atmosphere of quiet intensity.

Symbolism and the Flute’s Multiple Identities

The flute has long held symbolic and expressive associations in music history. Traditionally, it has been linked to pastoral and natural imagery, often appearing as a representation of harmony between humanity and nature.

Gubaidulina, however, extends these traditional symbolic roles of the flute by exploring its theatrical and mythological connections. The flute in her works often reflects both human and divine aspects, creating a dialogue between past musical traditions and modernist expression. She expands upon the Baroque-era concept of the flute as a dramatic character in musical storytelling, transforming it into a poetic and introspective voice.

Exploring Sound Through Timbre and Texture

One of Gubaidulina’s most significant contributions to flute repertoire is her Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion (1994), dedicated to Pierre-Yves Artaud. This large-scale work, lasting over 30 minutes, is a profound study in contrast and texture. The flute is positioned as a central voice within an ensemble that is divided into two groups, one tuned a quarter-tone lower than the other. This technique creates a haunting, shimmering effect, heightening the flute’s ethereal quality and enhancing the sense of duality – light and shadow, struggle and resolution, sound and silence.

Flute Works by Sofia Gubaidulina:

“Allegro rustico” for Flute and Piano (1963, 6 min.)

A vibrant and earthy piece, Allegro rustico captures the raw energy of folk traditions blended with modernist harmonic language, evoking a sense of untamed natural beauty.

Quartet for Four Flutes (1977, 14 min.)

A striking exploration of texture and timbre, this work demonstrates her fascination with polyphony and resonance, using four flutes to create an intricate web of sound.

Sonatina for Solo Flute (1978, 4 min.)

A deeply introspective piece that blurs the lines between speech and music, transforming the flute into a solitary voice, rich in expressive nuance and fragile intensity.

“Sounds of the Forest” (Звуки леса) for Flute and Piano (1978, 1 min.)

A miniature yet evocative piece, this composition paints an aural portrait of a forest, using delicate articulations and tonal shadings to mimic the sounds of nature.

“Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion” (1994, 33 min.)

Dedicated to Pierre-Yves Artaud, this monumental work is one of Gubaidulina’s most innovative contributions to the flute repertoire. It employs quarter-tone tuning, microtonal harmonies, and spatial effects, creating a mesmerizing interplay between the solo flute and divided orchestral forces.

“Impromptu” for Flute, Violin, and String Orchestra (1996, 15 min.)

A poetic dialogue between flute and violin, where both instruments engage in a dance of contrast—sometimes lyrical and flowing, at other times sharp and percussive.

“Warum” for Flute, Clarinet, and String Orchestra (2014)

One of her last works, Warum (Why) embodies the existential questioning that permeates much of her music, with the flute and clarinet engaging in an introspective and searching exchange.

Flute as a Reflection of the Human Condition

In Gubaidulina’s flute writing, one often encounters musical metaphors that reflect human experience. The flute’s breath, its ability to sustain long lines or break into fragmented gestures, mirrors the ebb and flow of human emotions – a sigh, a whisper, a cry. In her works, she frequently employs:

The Lamento Gesture – A descending melodic line, often associated with sorrow or longing, used extensively in Baroque music. Gubaidulina reinvents this gesture in her flute pieces, using it to evoke a sense of spiritual searching.

The Saltus Duriusculus – A rhetorical device from early music, involving an unexpected dissonant leap, symbolizing anguish or heightened emotional intensity. This can be heard in her Sonatina and Music for Flute, Strings, and Percussion.

Circular Motion and Eternal Return – Many of her pieces feature circular melodic gestures, with phrases returning to a central note, reflecting philosophical and existential themes of repetition, fate, and transformation.

A Composer Recognized on the Global Stage

Gubaidulina’s influence was not limited to instrumental music; she also made significant contributions to orchestral, choral, and film music. Her score for The Wrath of God (Der Zorn Gottes), performed by the Gewandhaus Orchestra under Andris Nelsons, was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition, a testament to her enduring impact on modern music.

Despite early struggles with recognition in the Soviet Union, her works are now performed worldwide, with greater frequency in European and American concert halls than in her native Russia. In 2011, she was named an Honorary Citizen of Kazan, and a contemporary music festival, Concordia, was founded in her honor, bringing together leading composers and performers each year to celebrate her artistic legacy.

A Lasting Legacy

Sofia Gubaidulina’s passing marks the end of an extraordinary chapter in contemporary music, but her voice lives on in her compositions. Her flute works, in particular, remain a cornerstone of the modern repertoire, challenging and inspiring flutists with their depth, complexity, and profound emotional resonance.

Reflecting on her impact, Kazan’s mayor, Ilsur Metshin, spoke of her as a “person of an era”, whose music and spirit remain woven into the cultural fabric of the city.

“Her name and fate are forever intertwined with Kazan. Her presence will always be felt in our city, in the streets she walked, in the center that bears her name, and in the hearts of Kazan’s people. For us, she remains an eternal figure, and her music will continue to speak for her.”

Her approach to composition – one that sought the spiritual essence of sound, that embraced the interplay between silence and resonance, and that gave voice to the ineffable – will continue to shape the way we think about music.

For flutists and musicians around the world, her legacy is not just a collection of works but an invitation to explore, to listen, and to seek meaning through sound. As long as her music is played, Sofia Gubaidulina’s voice will never be silenced.

Yulia Berry

www.yuliavberry.com

Yulia Berry is the founder of Flute Almanac, The Babel Flute, and the New England Flute Institute. A highly experienced flutist and mentor, she holds a Doctor of Music Arts degree from the Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (Russia).

Renowned for her virtuosity and expressive playing, she has performed as a soloist and chamber musician worldwide. An expert in flute pedagogy, she is known for her innovative teaching methods that emphasize technique, musicality, and artistry.

She has written extensively on the flute’s connection to art, culture, and history across different eras.

Great article. Sofia was a great composer. She helped expand the flute repertoire in a personal and detailed style. A great loss.

Vilma