Have you ever been frustrated in your practicing by inconsistent results? Some days you work and work on a phrase and have it nailed, the next day you can’t quite get it? Or you’ve tried all the traditional practice techniques but when it comes to performance they just don’t work?

Do you have students who’ve been working on the same issues for month? Despite your best efforts, they never seem to resolve it?

What’s missing is somatic inquiry.

What Is Somatic Inquiry?

- Somatic comes from the Greek soma, meaning “body.” But it refers to more than awareness of the body — it acknowledges that mind, body, and emotions form one inseparable whole.

- Inquiry means asking questions with curiosity, not judgment. Rather than seeking solutions, we ask to discover what’s true in the moment.

- Every thought, emotion, and experience has a bodily feeling. These are our lived experiences: our somatic reality. To be able to freely express music the way we want, we must learn the subtle distinctions between intellectual and embodied learning.

Somatic inquiry isn’t about anatomy per se – it’s about perception. How do you notice and respond to your body, your emotions, and your lived experience as you make music?

Why Don’t We Learn This?

Traditional music training emphasizes results: accuracy, pleasing the teacher, and avoiding mistakes. Rarely are we taught to notice or trust our bodies.

Even more, we are often actively discouraged from paying attention to our bodies. We are taught to ignore pain, to “just get over it” if we feel tension. When we are injured we don’t get help for all the related emotional difficulties: shame, anxiety, fear, performance worries, toxic self-judgment, and more.

But what if teachers asked questions like:

- What’s the essential connection between the jaw and the pelvic floor?

- How does standing differently change your sense of ease and support?

- How can you support your flute from below to keep tension out of your arms and hands?

- How does “sitting up straight” limit breathing and technique?

- How can you sit comfortably on a chair in rehearsals?

- Where do the nerves to your hands originate, and how does shoulder tension put them at risk?

All flute teachers could learn this basic body awareness. Taught in a somatic methodology, it could help prevent the staggering 70–85% injury rate among musicians.

Part I: Somatic Inquiry in Practicing

We all face three common practice challenges:

- Mastering difficult passages

- Deepening artistic expression

- Warming up effectively

1. Mastering Difficult Passages

You might be clamming on a run. You know you are tense, but not sure how to fix it. Instead of beating yourself up, get curious!

- When exactly does that tension arise?

- Where is it in the body?

- What does it feel like?

- Is there a thought associated with it?

- Is there a history with this particular run?

Pause – and process all of this. What resonates most with you?

Once you can answer those questions, then you can ask: “what do I actually have to do/not do with my body to play the way I want?

i.e., what are the subtle awarenesses I need, to play with ease?”

For example:

Can I approach this run in slow motion and maintain freedom in the body?

Am I missing support from the floor? What would happen if I were aware of my feet as I play?

What do I notice then?

Is that any different?

How?

What’s important is to stay curious and experiment. The answers lie within your experience – your SOMATIC reality.

2. Deepening Artistic Expression

This is challenging because it is so deeply personal, and because every flutist has a different idea about the best way to express, for example, the opening movement of the Prokofiev Sonata (or any other piece).

Start with these questions: how do I feel about the music? Have I done the work to analyze the piece and understand the composer’s intentions as best I can? Whatever part I’m working on, do I have a sense of what emotion would be meaningful here, at this time?

Expression may vary from day to day, from venue to venue, but that just gives you more options!

Cultivating an emotional understanding of a piece is actually a somatic process. Every emotion has a physical component.

Let’s say I want the opening to be peaceful. Am I able to enter a peaceful state, while still being able to produce the sound I want? It may involve work, but probably not physical and emotional tension. I ask the question: how do I need to use my body in order to make the music sound peaceful? How do I convey that to the listener?

I would start by imagining I am in a place where I can experience peace from a multi-sensory perspective. I imagine the sounds, smells, feeling of the air touching my skin, the colors, the space around me, the sense of the ground under my feet, my breathing, physical sensations, and my emotions. When I bring all that to my playing, I actually create a shortcut. Instead of thinking “I have to crescendo here or change my tonguing here or come up with a different tone color here,” the musical expression happens naturally. My musical intention of peace coordinates my body to produce that sound.

The lovely thing is that I don’t have to mark every nuance I want to play. I can let it be different each time, according to my imagination! By embodying the emotions I want in the piece, the musical expression will come out in a natural, authentic way.

3. Effective Warm-Ups

We need the whole body to play – every muscle, every cell, every sense, and every movement. We also know that the quality of our sound is determined by the quality of our movement.

So why not awaken the whole body, instead of going straight to the instrument?

A somatic inquiry warm-up might begin with some authentic movement – just letting your body move the way it wants to move today. Jerky, fluid, expansive, contractive, twisting or jumping – whatever arises. Explore the range of movement of your arms and legs. It might involve some vigorous whole body movement that will get your breathing going. Ultimately we want circulation and innervation of the whole body.

There’s also musical movement. The work that I did in Dalcroze Eurythmics training was essential for experiencing this. Moving to music in a way that expresses the qualities of the music is invaluable in learning to embody music. Imagine what it would feel like to play a piece after you have “danced” it! What I love about this process is that it also brings innate joy and creativity to practicing that sometimes becomes tedious and over-intellectual. Your whole body will support whatever artistic articulation, vibrato, phrasing, or dynamics that you would like.

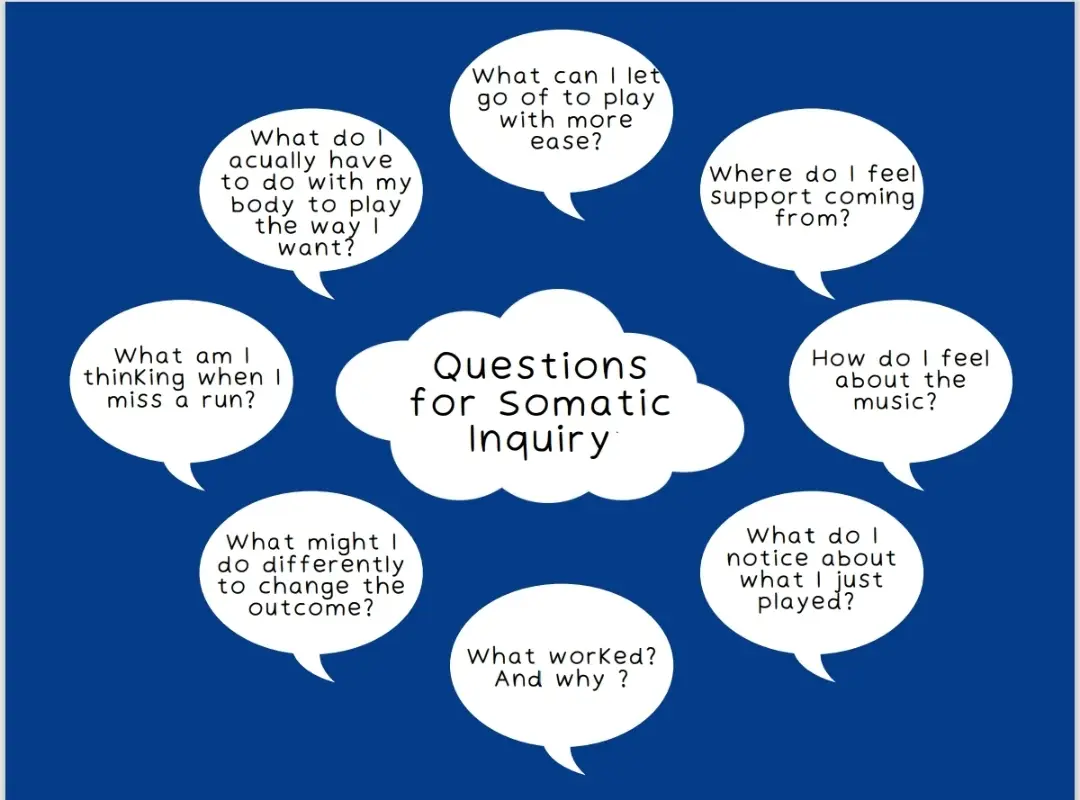

In all three of these somatic explorations: technical difficulties, artistic expression, and warmups, you will find these kinds of questions are at the heart of your practicing.

What am I noticing about what I just played?

What worked? What did not come out the way I intended?

What might I do differently to change the outcome?

Part II: Judgment and Emotion

In somatic inquiry we work with curiosity, not correction. Observation, not judgment.

Because traditional teaching is correction-based, many classical musicians learn what they do wrong from the beginning. They are taught to be aware of errors and try to correct them. It doesn’t take much imagination to realize how this might cause a young child to be self-critical. Ultimately it can develop into the kind of toxic self-judgment that cripples musicians. Never being good enough. Always anxious about getting it right. Feeling competition with peers and colleagues. Worrying about corrections from teachers, band directors and conductors. Performance anxiety, imposter syndrome, burnout, and of course, injury, depression and anxiety.

Nurturing our ability to be evaluative, versus judgmental, can be a valuable paradigm shift for musicians. What works? Was it the attack on that third note that didn’t quite seem right? What do I want? What do I need to do with my body to make that attack come out the way I want? Is it changing the air, the tongue, the way I’m standing, the tension in my hands? The right question will resonate and a lead you to a solution.

It’s also important to include past experiences in your questioning.

Maybe you had a performance of this piece that didn’t go so well. Is that anxiety still living in your body? If so, it will take a little work to release that experience and come back to the present.

Did you have a teacher who criticized you about this particular piece?

Did you play it in a competition and do badly? Did you play it someplace and do really well?

Becoming musically embodied means being totally in the present with the music, and letting go of past associations.

Someone once asked Itzhak Perlman how he could play the Beethoven Violin Concerto 200 times. He answered: “I imagine that this performance is the last time I will get to play it.” That’s being present with a piece of music!

The dark side is when you have had a traumatic experience or series of experiences related to playing or teaching.

If you had a teacher with whom you experienced anxiety in your lessons for a few years or even a few weeks, that anxiety will live in you every time you pick up the flute. I’ve worked with many flutists who can’t even think about playing, let alone pick up the instrument, without getting tense and anxious. I was one of them. In that situation, practicing is not very productive.

If you’ve had experiences where you were humiliated or abused by a person with power over you, that can also be extremely difficult. You can’t just “let it go.” You need to do the somatic work to heal the trauma.

I’ve created a list of resources at the end of this article so you can begin to explore that if you wish. In general, for musicians, cognitive behavior counseling can be a good start to understand what happened, but many of us find that somatic therapy, which deals with the feeling of the experiences in the body, is the ongoing way to release stored trauma. “The Body Keeps the Score,” as Peter Levine says in the title of his famous book.

Part III: Somatic Inquiry in Teaching

Curious about how to bring somatic inquiry into teaching?

Somatic inquiry transforms lessons into collaborative, empowering spaces. Three simple strategies can make the difference:

1. Be Present

Enter each lesson without expectations, and be truly curious about what the student experiences. Do not assume that you know what they are thinking or feeling.

2. Ask, Don’t Tell

As experienced teachers, we often know what the student can do to solve a problem. Yet if we tell them, it takes away from the process of figuring it out for themselves. Essentially, it eliminates their power and agency. Instead, ask questions like, “what did you notice about that? What were you thinking about when we got to that section in the piece?” Always be ready to ask follow up questions.

Validate honestly their answers. “Yes, it seemed that way to me!” or “Yes, that seems to really work for you!” and then ask more questions.

“What did you really want to achieve? What do you think you need to do to get there? What do you think is getting the way?”

Then, if you need to, you can offer your expertise of something that you think might work. “May I offer you a suggestion? Lots of people have found that if they articulate this this way it comes out a little more clearly. Would you like to try that?”

Accept the fact that you can never know what they are thinking or feeling, and you can’t “fix” them. If what you suggest is radically different from what they are processing on their own, you will lose that teaching moment. They will suppress their own thoughts and try to do what you want them to do. Offer suggestions after students process their own experiences.

3. Celebrate!

Help students recognize and embody successes – small or large. Frequent celebration rewires the body against the weight of self-criticism.

“Did you hear how that phrase came out so beautifully? Isn’t that awesome?!”

Do a little celebration dance. It may seem hokey, but I tell you, this is your job. It takes hundreds of thousands of little celebrations to combat the millions of self-judgments that are already living in their bodies. If they can recognize what they are doing well, they will be able to do it again!

For example: they say “yeah, that time I could really feel my feet on the ground. Wow!”

You: “What did you notice about how that changed your playing? How did that feel? How do you feel about that? Yay! Let’s do it again so we can know what really works!”

“Did you hear what a gorgeous sound that was? How did you feel about it?

Did you notice? No?

Let’s do it again and this time see if you can hear what it sounded like when you went down into your hips and knees and ankles a little bit on those high notes!”

What’s particularly awesome about teaching with somatic inquiry is that it’s easily accessible and adaptable to students of any age, level, or learning style.

Beginners

Celebration is essential. They are trying to learn so much that they need you to validate and name what works. They may need 20 times of getting sound from the head joint to counter the 10 times that they didn’t. (This applies to adult beginner as well.)

They’ll need to experience holding the flute to get the feeling of balancing it many times before they’re asked to coordinate that with blowing or even with reading music. Remember how children learn – they repeat and repeat and repeat until it’s completely in their bodies. If you move them too soon to another task they will lose the one that they were just starting to learn.

Intermediate students.

If you’ve been asking them questions all along, they’ll be in great shape. If you have a new intermediate student whose opinion has never been considered, it will take some time for them to feel comfortable saying what they think. You can start with, “what did you notice?” If they say “I don’t know,” you can be more specific. “What did you hear in the sound? What did your breathing feel like? How did that feel in your hands?”

Ask musical questions. ”How would you like this piece to sound? What kind of energy would it have?”

They say, “I don’t know.”

You: “If you did know, what would you say? If you were teaching somebody else, what would you tell them?”

If you see them fishing for the “right” answer, be clear: “there are no right answers. I’m only interested right now in what you think, what your experience is. Your perspective is valuable.” You may be the first person to ever tell them that.

Advanced students

Here is where you can really dig into the nitty gritty of how they are using their bodies to create sound, into their artistic vision of a piece, and into how to become their own teacher.

“Lets play this 3 times with 3 different emotions or characters. What would you like to choose?” “Which, if any, worked the best for you? How could you make it even more powerful? What other musical explorations might you like to try?”

Help them learn to trust their own instincts and experiences, so if they ever get into a situation where they are being taken advantage of, they will know how to take care of themselves.

Help them learn the value of individual artistry, so they won’t be devastated by competition.

And above all, teach them to trust their bodies so they will be instantly aware of anything that feels wrong.

In Summary

Somatic inquiry helps us:

- Play with greater ease and freedom

- Express music authentically

- Warm up in body and spirit

- Transform self-judgment into curiosity

- Teach in ways that empower students of every age and level

- Ultimately, teach students to trust their instincts, their artistry, and their bodies — essential tools for resilience in a competitive, high-pressure field.

Be present. Ask questions. Celebrate.

When we embrace somatic inquiry, practicing and teaching become joyful, embodied, and sustainable — for ourselves and for our students.

If you find these ideas stimulating, consider joining “Teaching Unleashed.” A new cohort of this six-month weekly professional development course begins October 15.

With master classes, mentored teaching, community support, Body Mapping strategies and so much more, you’ll get a whole new energy for teaching!

The Power of Somatic Inquiry: Related Reading

- Daniel, R. & Parkes, K.. Music Instrument Teachers in Higher Education: An Investigation of the Key Influences on How They Teach in the Studio. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29, 1, 33-46, 2017.

- Levine, P. Waking the Tiger. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1997.

- Pearson, Lea. Body Mapping for Flutists: What Every Flute Teacher Needs to Know about the Body. Chicago: GIA Publications, 2006.

- Pearson, Lea. Cultivating the 21st Century Garden: nurturing pain-free, resilient, and confident musicians. The Babel Flute. June, 2023.

- Pearson, Lea. Safety and Spaciousness in the Studio: requirements for growth. The Flute Almanac, December 15, 2024.

- Polatin, Betsy. Humanual (A Manual for Being Human). Cardiff-by-the -Sea: Waterside Productions, 2020.

- Pozo,J. I, Pérez Echeverría, M. P., López-Íñiguez, G., & Torrado J. A. Learning and Teaching in the Music Studio: A Student-Centred Approach. Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education, 31, 1st ed. Springer, 2022.

- Salonen, B.L. Tertiary Music Students’ Experiences of an Occupational Health course Incorporating the Body Mapping Approach. [PhD dissertation].

- Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. Available at: https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/ handle/11660/9652 , 2018.

- Strozzi-Heckler, Richard. The Art of Somatic Coaching. North Atlantic Books, 2014.

- Shoebridge, Shields & Webster (2017) Minding the Body, An Interdisciplinary theory of optimal posture for musicians. Psychology of Music, 45(6), 821-838.

- van der Kolk, Bessel.The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books, 2015.

DOWNLOAD THE RESOURCE LIST (PDF)

Lea Pearson

Music Minus Pain | Transformational Teacher Training Program | Crack the Codes of Breathing and Tension

Lea Pearson, DMA, has been studying education, psychology, movement, anatomy, neuroscience, Body Mapping, the Alexander Technique, entrepreneurship, leadership, performance practice, and Dalcroze Eurhythmics since 1970.

A licensed Body Mapping Educator, she is an award-winning Master Teacher, a Kennedy Center-trained Teaching Artist, a Fulbright Scholar, and a Certified Health Coach. Formerly a member of the South Bend Symphony, Jackson (MI) Symphony, and a sub with the Toledo Orchestra, Lea performs works by women, Black, and other under-represented composers.

Her dream is that every musician will share their artistic vision with joy and ease – wherever, whenever, and for as long as they want. To that end, she trains teachers in the Transformational Teacher Training Program “Music Minus Pain“.