In this article I will attempt to present the origin of the tsakan (csakan or csákány) from a Hungarian perspective in connection with a notable historical figure.

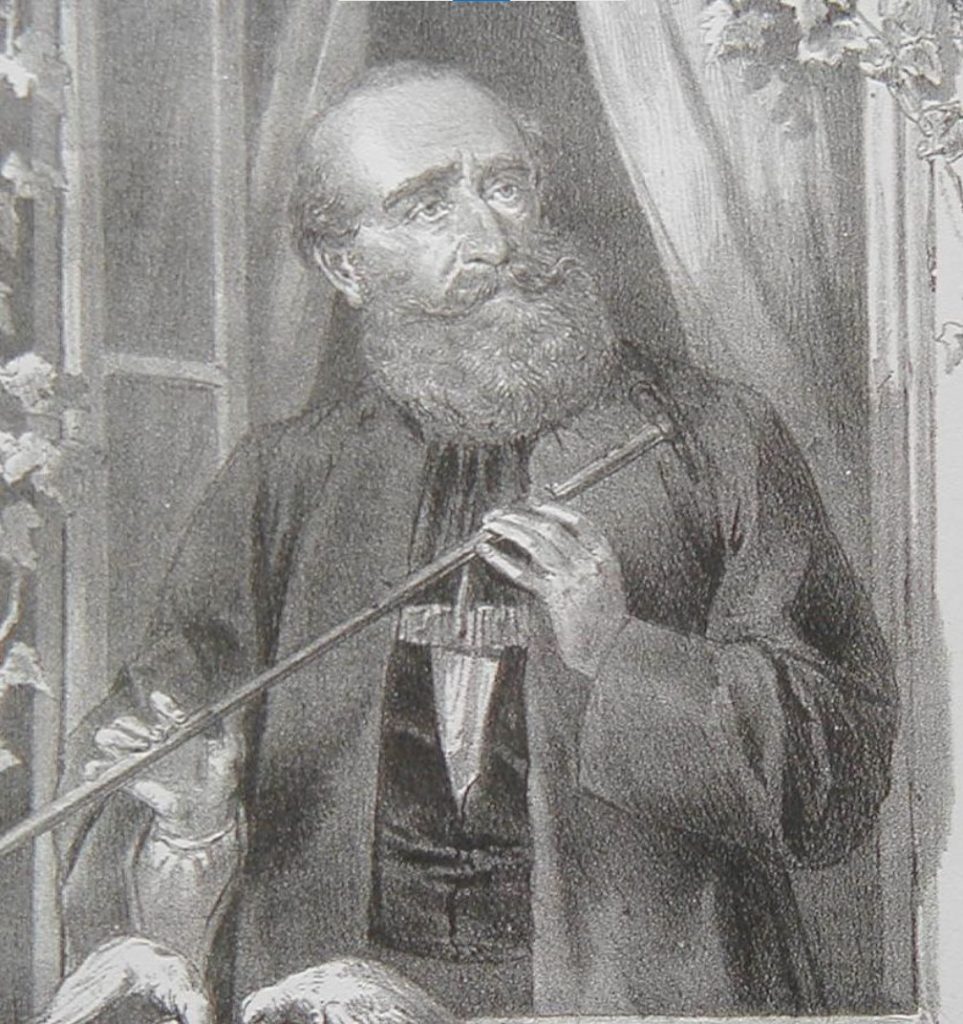

The first piece of Ferenc Liszt’s Historische ungarische Bildnisse (S.205) is dedicated to a hungarian nobility, Count István Széchenyi (1791–1860) who was a Hungarian statesman, writer, and reformer widely regarded as “the Greatest Hungarian.” Born into nobility in Vienna, he dedicated his life to modernizing Hungary during the 19th century. It is no coincidence that Liszt dedicated a musical memorial to the count, as this noble personality himself was of a musical nature. Count Széchenyi played a musical instrument that is less well-known today, but was wildly popular in his time. It was the so-called Tsakan („csákány” on hungarian).

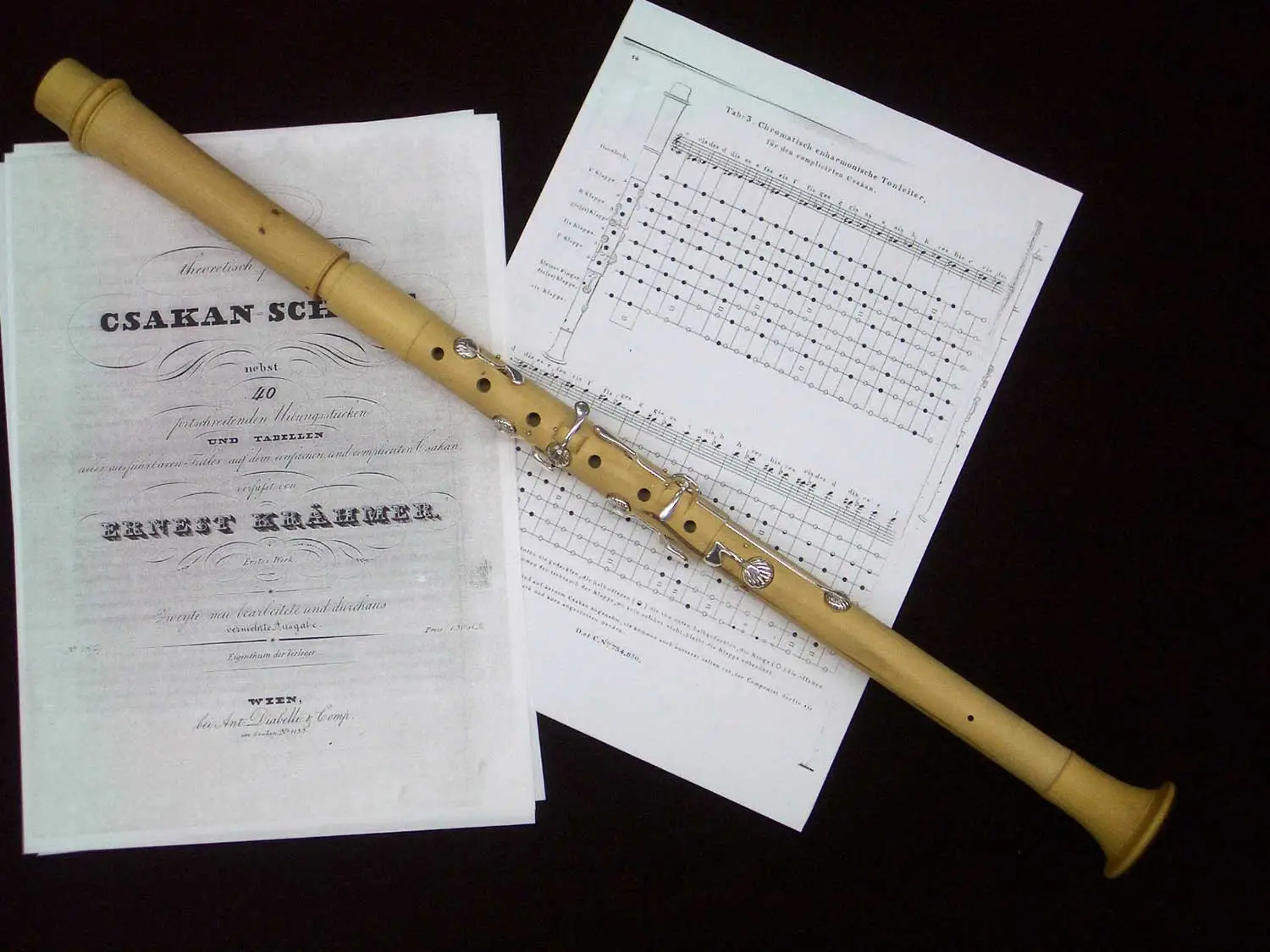

This instrument was extremely popular in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy between 1820 and 1850. The first educational tutor was published in 1821 by Ernst Krähmer (1795-1837) in Vienna, it was his op. 1 work, entitled Neueste theoretisch practische Csakan-Schule. In this work, Krähmer describes the origin of the tsakan as he knows it. According to the somewhat romantic story, a wandering musician found the instrument in an abandoned hermit’s cave, restored it, and than had it played.

The first documented player of this instrument in Hungary was Anton Heberle (1780 — 1816), who was born in Veszprém, Hungary. Heberle was the first who plublished works for Tsakan and as an „entr’acte”, he entertained the audience in the theaters of Pest and Buda on his instrument. Hungarian sources suggest that he the same person is like „Eberle in Papa” (Pápa is a hungarian town in western part in Hungary) and other writers from the 19 century believe that the tsakan is a Hungarian invention. In addition to Heberle and Krähmer, Diabelli also composed music for this instrument, as did the Pest-Buda doctor, János Keresztély Hunyadi (1807–1865).

The tsakan itself existed in two version, simple only one key and advenced with seven key (einfach and kompliziert). The tsakan had two main forms of appearance, in Vienna it was shaped like a walking stick, while in Pest-Buda it was also a walking stick too, but with a axe-like head, that was a kind of traditional wapon. However the tsakan at this time was absolut popular in Vienna and Pest and Buda as well, more than 400 compositions were written for this instrument.

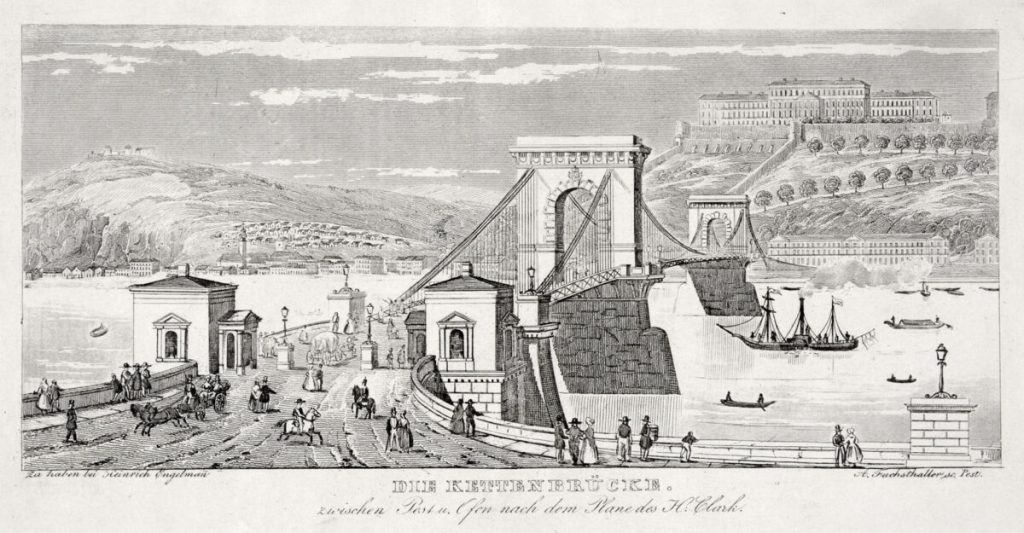

Count István Széchenyi’s initiatives covered all areas of life. In 1825, he founded the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, promoted steam navigation on the Danube and Lake Balaton, supported railway development, flood protection and agricultural innovation. If you visit Budapest, you can see this emblematic “Chain Bridge” in the middle of the city, the construction of which he himself promoted. Széchenyi imported Thoroughbreds from England, developed horse breeding and is credited with founding hungarian horse racing.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, several members of the family were musical, many of whom played instruments and composed music in various genre.

The Count’s trip to England took place in 1815, at a time when gentleman flute playing was at its peak. Although there is no direct evidence that Count Széchenyi was touched by English flute culture, he himself was a practitioner of the Tsakan. Also this instrument accompanied him throughout his life, but there is no evidence that he displayed his art in a narrow or wider circle of society. According to his diary, he primarily played Hungarian melodies for his own amusement. This instrument helped him through difficult spiritual times. He regularly went to the theater and concerts, highly appreciated Rossini’s music, but considered Paganini’s virtuosity to be excessive. He met Franz Liszt several times, attended his concerts, and even hosted him at his home, and Széchenyi cited Liszt’s diligence as an example in his admonitions to his son.

Krähmer dedicated one of his work to Széchenyi („Comte Etienne Szecheniji”), written for tsakan and piano. It is the Variations brillantes, Op.18, that was published 1823 in Vienna. The piece itself show less hungarian manner, but clearly followed the beloved and usual variation from at this time. The composition begins with a fifteen-bar piano solo, followed by the theme that is pleasant, witty and a little funny as well. Then comes the six variations, each in two parts-form, with repetitions. Most of them are very melodic and virtuos, except the fifth variation, which is minor, slow and more lyrical. The sixth variation is preceded by a short solo cadenza for the chakan. This last variation conclude with a coda-like virtuoso section. The musical material of almost all variations contains chromatic parts. There is no evidence as to how Széchenyi felt about the work or where he performed it, but it is clear that its musicality was well known among Viennese composers.

His influential books — Credit, World, and Stadium — outlined bold economic and social reforms. He believed Hungary’s progress depended on education, infrastructure, and cooperation with the Habsburg monarchy. Perhaps this is why Széchényi was disappointed after the failure of the 1848–49 Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence, which was a serious conflict between the Monarchy and the Kingdom of Hungary. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to a mental institution in Döbling, near Vienna, in 1849. Though many considered him insane, he was actually battling severe depression and psychological distress, worsened by political disillusionment and personal setbacks.

In these days was noted that his use of the Tsakan was always played in a monotonous manner, and he ideologized that he always played the same tune because – as he stated – he had to force himself to endure the constant mental pain. According to modern researchers the “use” of music on this way was in this period therefore shows less the signs of artistic enjoyment than of therapeutic practice.

At the end of the 1850s, especially around 1859–60, Széchenyi continued his political activities behind the scenes. He secretly wrote and distributed pamphlets criticizing the authoritarian system centered in Vienna. Döbling became the intellectual center of opposition thinkers, but on April 8, 1860, Széchenyi took his own life in Döbling. His death shocked Hungarian society and remains a subject of debate and reflection to this day.

His legacy lives on in Hungarian institutions, public spaces, national memory, and in two compositions written for him by Franz Liszt and Ernst Krähmer, the latter specifically for the count’s favorite instrument, for the csakan.

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi

www.czeloth.com | ORDER BOOK “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration“

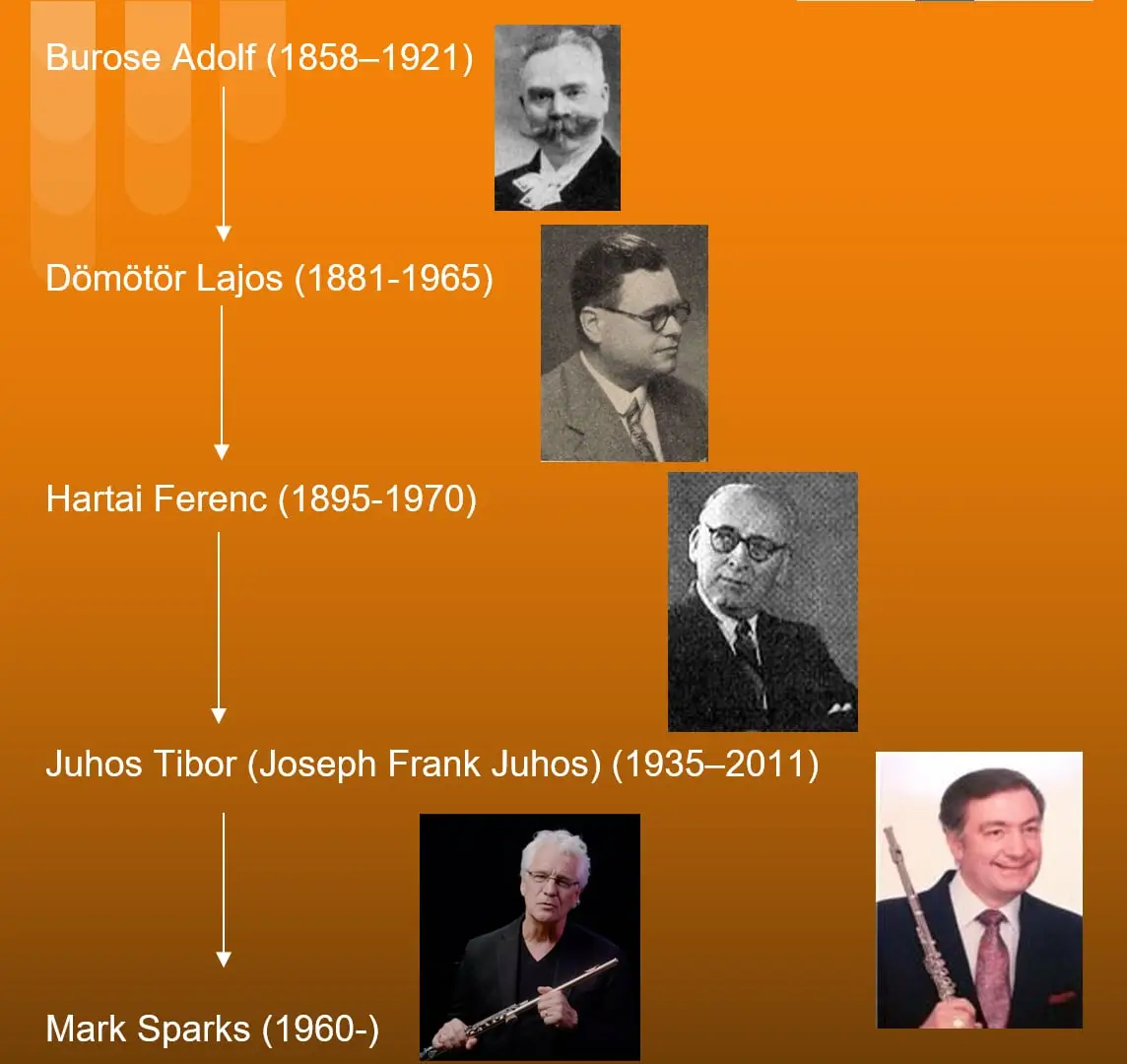

Mr. Czeloth-Csetényi, Gyula plays the flute since his age of 10. He went to the Bartók Conservatory, then he studied at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. After the demolition of the iron curtain he was the first to visit Sir James Galway’s Seminar from Hungary in Switzerland between 1993 and 1995. He was Dr. Jochen Gartner’s student at the Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich.

Gyula Czeloth-Csetényi has made his first CD recording of Gamal Abdel-Rahim’s compositions there. He graduated “Cum Laude” in 1997 at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. Between 1990 and 1999 he has been the editor and publicist of the journal of the Hungarian Flute Association. Beside his classic repertoire he plays at a jazz band where his own compositions are performed, too. He played together with recognized jazz musicians.

As classical flutist he has performed all over Europe and in Japan. He made a solo CD in 2001, its title is “12 Romance”. He is a co-lead author of the book under title – “The last two hundred years of Hungarian flute playing and its European integration”. The book was published in 2022.