Author’s Note:

This article revisits and expands on ideas I previously explored in an earlier essay on flute timbre and expression. With a fresh perspective and deeper exploration, it offers new insights into the emotional and artistic potential of the flute’s voice – its colors, its roles, and its evolving use in music across time.

Like the human voice that created it, the flute can express a vast spectrum of emotions. Its sound can be joyful or sorrowful, passionate or mournful, ethereal or commanding. Much like a spoken word in a performance, the flute’s tone is never static – it adapts to the emotion behind the music, reflecting the mindset of the composer and the sensitivity of the performer.

This expressive flexibility highlights an important pedagogical and humanistic principle: the value of individuality. Every performer – every student – is unique, just like every voice in the orchestra. And the flute, with its ability to transform emotionally and stylistically, becomes a powerful tool for nurturing this individuality.

The Art of Flute Performance and Pedagogy

Modern flute performance sets a high bar, both in solo and ensemble settings. To meet this demand, a flutist must possess:

- Mastery of the instrument’s full technical and expressive potential

- Ensemble and orchestral experience

- A refined sense of musical style and aesthetic

No two musicians are the same – and the teacher’s role is to help each student discover their own voice, their personal palette of tone colors and expressive tools. Teaching flute requires not only musical skill, but also a deep understanding of psychology, pedagogy, and human development. These are essential for guiding students toward artistic and professional success.

As flutes evolve and new techniques emerge, performers are challenged to expand their interpretive range. Central to this is the exploration of timbre – sound color imbued with spirit and meaning, capable of becoming a medium of artistic communication.

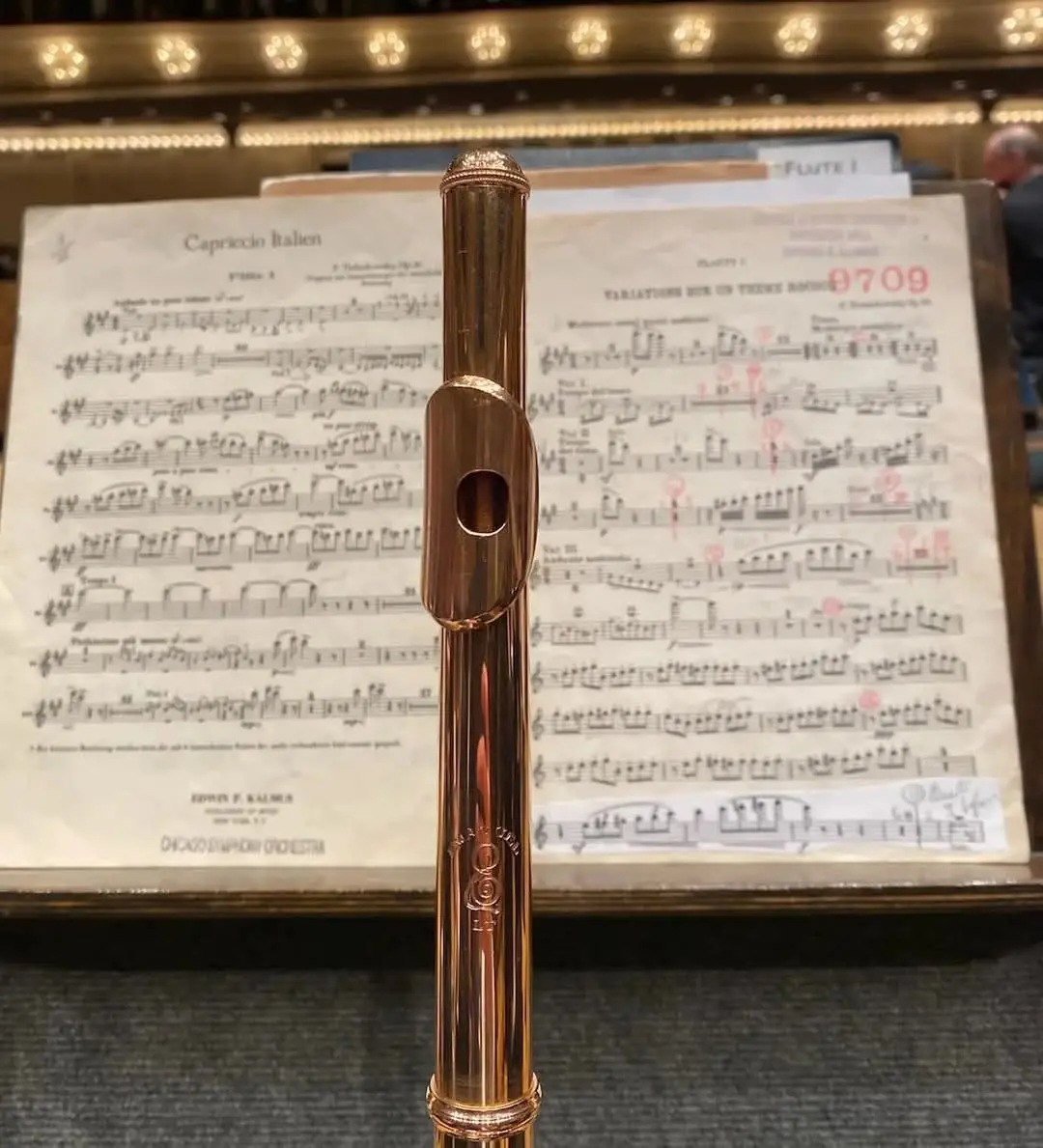

The Sound Characteristics of the Flute

The flute’s tone resists categorization, but here are just a few descriptors that capture its magic:

Airy, bright, soulful, silvery, whistling, whispering, warm, filigree, graceful, poetic, mellow, brilliant, clear, deep, dark, ethereal, aspirated, sighing, buzzing, and saturated…

Feel free to expand this list—each word opens a window into the flute’s personality.

Timbre Variations Across Registers

- Low Register (B3–G4): Often described as dark, reedy, mysterious, and covered. It adds depth and subtle warmth to orchestral textures.

- Middle Register (A4–D5): The most balanced and versatile, round and lyrical—a core part of the flute’s character.

- High Register (E5–C7): Bright, brilliant, sometimes piercing. Perfect for floating above the orchestra or evoking birdsong and enchantment.

Timbre and Articulation

Timbre is also shaped by how the note begins:

- Legato reveals the singing, lyrical aspect of the flute.

- Staccato makes it playful and agile.

- Flutter-tongue, harmonics, air tones, and overblowing provide a contemporary vocabulary for expressive effects.

The flute’s timbre is transformed by articulation, from a breathy sigh to a biting edge – each attack is a stroke of character.

Composers on Flute Timbre

Hector Berlioz

A flutist himself, Berlioz devoted several pages of his Treatise on Instrumentation (1844) to the flute’s evolving character. He lamented how composers often overlooked the expressive power of the lower register, writing:

“Modern masters kept the flutes too persistently in the higher ranges… they always seem afraid they will not be sufficiently clear amidst the mass of the orchestra… instrumentation becomes hard and sharp rather than sonorous and harmonious.”

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

In his Principles of Orchestration (1896–1908), Rimsky-Korsakov explored the nuanced palette of woodwinds. He noted:

“Individual timbres lose their characteristics when associated with others… Melodies demanding diversity of expression should be entrusted to solo instruments of simple timbres.”

He described the bass flute as colder in color, crystalline in its upper range, yet used it in works like Mlada, Sadko, and The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh.

Orchestral Blending and Timbre Combinations

- With strings, the flute floats above, creating a transparent veil.

- With harp or celesta, it creates a dreamlike, bell-like color.

- With oboe or clarinet, the blend becomes richer and more layered—yet careful balance is needed to preserve expressive clarity.

Mahler, Debussy, and Strauss masterfully blended the flute to evoke mysticism, memory, and even irony.

The Flute Through Time

Before the Renaissance, flutes were military and festive instruments. By the Baroque era, composers recognized their ability to convey tenderness. Romanticism elevated this even further, embracing the flute’s emotional expressiveness.

In early opera, composers like Caccini (Eurydice), Monteverdi (L’Orfeo), and Cesti (The Golden Apple) used flutes to evoke pastoral imagery. Later, Rameau and Gossec integrated them more deeply into the orchestra, opening the door to a new era of virtuosic flute writing.

Nature’s Voice: The Flute as Imitation

The flute excels at imitating natural sounds, especially birdsong and flowing water:

- Tchaikovsky, The Queen of Spades – pastoral duet

- Haydn, The Seasons – birds and thunder

- Mussorgsky, Night on Bald Mountain, Dawn on the Moscow River

- Beethoven, Pastoral Symphony – nightingale

- Grieg, Morning Mood

- Mahler, Symphony No. 2 – awakening nature

- Prokofiev, Peter and the Wolf – character of the bird

- Messiaen, The Awakening of the Birds – flute as thrush

In Honegger’s works, flute birdsong symbolizes hope and peace amid sorrow.

Folk Dances and Festive Scenes

The flute brings life to dance and folklore:

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade – folk dances

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Capriccio Espagnol – vivid cadenzas

- Ravel, Bolero – sultry low-register solo

- Mendelssohn, A Midsummer Night’s Dream – fluttering scherzo

Fairy Tales and Magic

The flute often paints magical, whimsical characters:

- Rimsky-Korsakov, The Snow Maiden

- Stravinsky, The Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring

- Lyadov, Kikimora, Baba Yaga, The Enchanted Lake

Sorrow and Loneliness

The flute becomes a voice of grief and isolation:

- Ravel, Pavane for a Dead Princess

- Tchaikovsky, Third Suite “Slow Waltz”

- Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice – timeless lament

In Shostakovich:

- Symphony No. 5 – farewell duet with horn

- Symphony No. 6 – introspective opening

- Symphony No. 7 – biting irony of the “invasion theme”

- Symphony No. 15 – grotesque, Brueghelian flute theme

The flute can carry grief with transparency—never heavy, but deeply felt.

Lyrical and Poetic

Romantic and modern composers reveal the flute’s lyrical soul:

- Debussy, Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

“The flute of Debussy’s Faune breathed new air into the art of music.” – Pierre Boulez

- Mallarmé to Debussy:

“Your music… goes much further into nostalgia and light.”

Seductive and Charming

The flute seduces through delicacy and refinement:

- Ravel, Daphnis and Chloe – charm, sensuality

- Bizet, Carmen, Act III Intermezzo – freedom and natural beauty

Contemporary Timbre Explorations

In the 20th and 21st centuries, composers have increasingly explored the flute’s timbre as a core expressive element—not just for melody, but for texture, gesture, and emotional contrast.

Modern techniques such as multiphonics, whistle tones, air sounds, pitch bending, flutter tonguing, and key clicks expand the instrument’s vocabulary far beyond traditional sound. These tools allow flutists to evoke everything from ancient winds to electronic textures or human breath.

Composers like Kaija Saariaho, George Crumb, and Robert Dick use these techniques to create immersive sonic worlds where the flute becomes elemental – no longer just an instrument, but a force of nature.

“Timbre and rhythm are no longer decorative elements—they are the very core of the composition.”

— Pierre Boulez, Orientations (1981)

Boulez’s flute writing, especially for alto and bass flutes in works like Le Marteau sans maître, emphasizes blurred edges, breath-infused tones, and spectral color shifts.

Similarly, Carl Nielsen gave the flute a sharp character in his Flute Concerto (1926), writing:

“The flute is the eternal questioner, sensitive and sincere, sometimes naïve – at odds with the world yet always singing.”

This ambivalence is expressed through sudden tonal changes, ironic gestures, and exposed, unaccompanied lines.

In more recent decades, composers have embraced the flute’s fragility and transparency as a metaphor for emotional states. Whether as a birdlike whisper in Takemitsu, a mournful breath in Harrison Birtwistle, or a shimmering veil in Saariaho, the flute’s timbre has become a tool for shaping time and space.

Today’s flute timbre is no longer just one voice – it is a full emotional spectrum, from pure tone to raw breath, from lyricism to noise.

Conclusion

Trying to pin a single expressive label to the flute is impossible. It is an instrument of transformation – of many voices, many moods, and limitless emotional nuance.

Let the final word come from the mystic poet Rumi:

“The fluteplayer puts breath into a flute, and who makes the music? Not the flute. The Fluteplayer!”

This simple yet profound metaphor captures the essence of everything explored in this article. The flute, for all its beauty and versatility, is merely a vessel. It is the musician – the Fluteplayer – who breathes life into it, shaping its timbre, unlocking its emotional spectrum, and transforming it into an instrument of expression.

The quote reminds us that the true source of artistry lies not in the instrument itself, but in the soul and intention of the one who plays it. In performance and in teaching, this principle affirms the value of individuality, the power of expression, and the endless possibilities contained in a single human breath.