Il viaggio di Georges Barrère in America

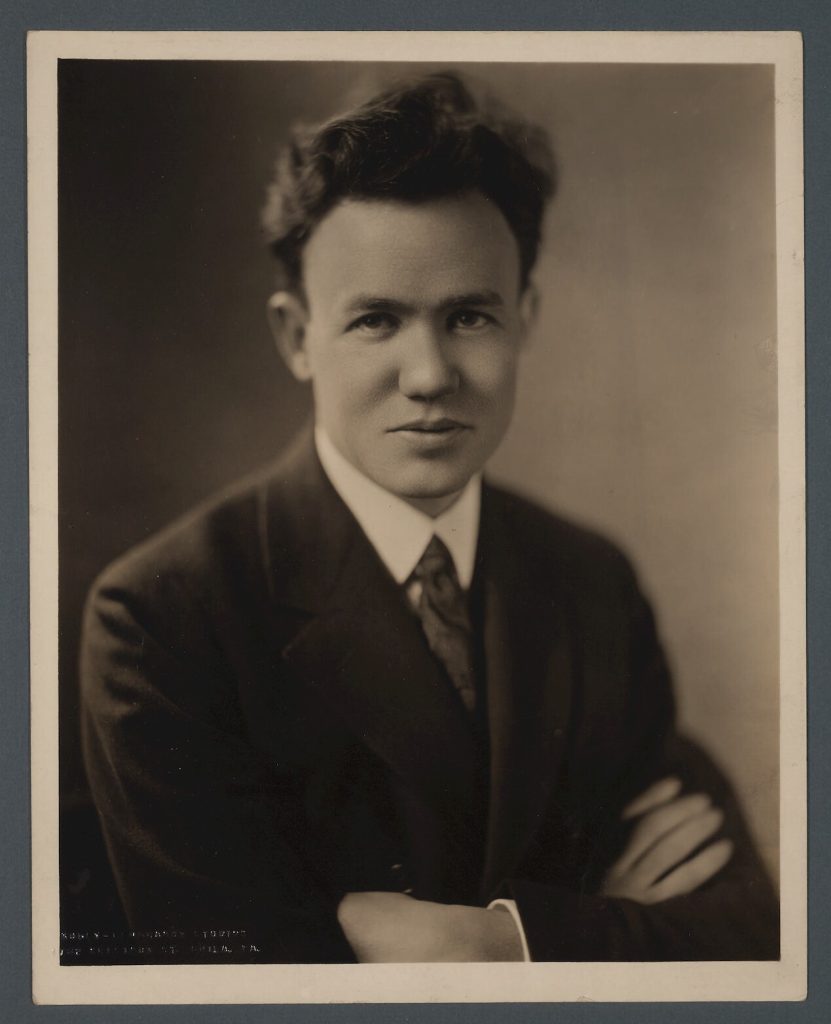

Per sostituire il deceduto primo flauto Charles Molé, ingaggiato nel 1903, Walter Damrosch, direttore della “New York Symphony Orchestra”, recatosi a Parigi portò con sé negli Stati Uniti, su consiglio di Paul Taffanel, Georges Barrère. Barrère lasciò quindi il suo incarico di flautista e direttore della Société Moderne a Louis Fleury e si stabilì in America, raggiungendo in breve tempo notorietà, tanto che Leonardo De Lorenzo riportò il cambio di Scuola attuato dagli allievi di Wehner:

When Barrère reached New York the grand old man [Wehner] still enjoyed considerable prosperity because of his large class of pupils. That, however, did not last long because Barrère’s immediate success was so great that, as far as flute and flute playing was concerned, there was one, and only one – Barrère! With very few exceptions, all the pupils of Carl Wehner left him, changed their flutes from wood to silver, and a number of them, knowing nothing of the fact that the origin of the Boehm flute was logically an open G-sharp key instrument, even changed from open to closed G-sharp key flute!

De Lorenzo 1992: 461

Come vennero abbandonati gli insegnanti tedeschi, così i loro strumentisti trovarono sempre meno spazio nella vita musicale di New York. Il Musical Courier n. 51 del 25 ottobre 1905 scriveva:

New York has had some notable exponents of the German school of woodwind players in the past, but it seems to be generally accepted now that the French school is superior.

Musical Courier in Toff 2005: 89-90

Una testimonianza d’epoca viene da Fitzgibbon, il quale nella prefazione alla ristampa del suo saggio del 1928, aggiorna i lettori sulla situazione del flautismo statunitense a cavallo tra Ottocento e Novecento:

Owing to Heind’l and other pupils of Boehm settling (circa 1864) in USA, the German style and music became prevalent, but since 1914 French musicians have superseded the Germans in the principal orchestras, so that French style and music now take the lead .

Fitzgibbon 1928: the

È sulla base dell’abilità esecutiva che bisogna ricercare, dunque, il motivo dell’acclamazione degli strumentisti a fiato francesi. Poco dopo il loro arrivo Frank Damrosch, fratello di Walter, fece loro occupare le cattedre dell’Institute of Musical Art (ora Julliard School), da lui creato e inaugurato a New York il 31 ottobre 1905 su riferimento del Conservatorio di Parigi, di cui Barrère divenne fondatore e direttore del dipartimento “fiati”.

Georges Barrère, come il suo maestro Taffanel, non si limitò all’attività dell’insegnamento: fondò la “Barrère Little Sympony” e la “Barrère Ensemble of Woodwind Instruments”, esortando i compositori contemporanei a scrivere musica per flauto, e nel 1920 “The New York Flute Club”, la sesta associazione flautistica cittadina allora esistente in America, e l’unica tra quelle ancora oggi attiva. (Nancy Toff riporta che la prima associazione flautistica realizzata negli Stati Uniti fu il “Los Angeles Flute Club” (1916), a questa seguirono le associazioni delle città di Twin City (marzo 1920), Seattle (marzo 1920), St. Louis (ottobre 1920) e Pittsburgh (dicembre 1920). Nessuna tra queste, tuttavia, ebbe negli anni un’attività continuativa come “The New York Flute Club” (Toff 2005: 380))

Scrisse, inoltre, il metodo The Flutist’s Formulae: A Compendium of Daily Studies on Six Basic Exercises (1935) e contribuì a pubblicizzare la ditta Haynes & Co. di Boston a partire dal 1913, anno in cui vi comprò il suo primo strumento in argento, dalla quale acquistò nel 1927 un flauto d’oro 14k e nel 1935 il primo flauto al mondo ad essere costruito interamente in platino.

Per tale strumento Edgar Varèse compose ‒ su invito dello stesso Barrère ‒ il brano per flauto solo Density 21.5, suonato la prima volta il 16 febbraio 1936 (Powell 2002: 230).

Barrère rilevò nel suo flauto di platino, dal materiale particolarmente denso,

«[a] greater brilliancy in the high register, a beautiful mellowness in the medium range and a rich fullness in the lower notes […] But perhaps the most important factor… is that both volume and the quality of the tone are better».

Barrere in Toff 2005: 278

In 1922 the William S. Haynes Co. added new ‘French’ model flutes with perforated keys. The ‘handmade French’ version was built on a thinner silver tube (0.03 inch), though to be more responsive, and like those of Lot it had soldered toneholes with keys set in line and pointed arms connecting them with the rods, while the ‘ regular French’ model, made of thicker tube, had an offset G mechanism. Haynes promoted the new open-flute as superior to his earlier type: ‘Undoubtedly the players who take the trouble to adapt themselves to the French model flute become better musicians. As for the instrument itself, it is characterized by a greater clarity and brilliance of tone than that of the covered hole flute.

Powell 2002: 230

Flautisti francesi e il loro impatto sugli Stati Uniti

Nonostante un articolo apparso sul bollettino del The New York Flute Club riporti un minimo albero “genealogico” della Scuola americana dove vengono citati i seguenti allievi di Georges Laurent, stabilitosi in America nel 1918: James Pappoutsakis, Robert Willoughby, Lois A. Schaefer, Harry Moskovitz, Bonnie Lake (Hulbert 2011: 5), a cui vanno aggiunti Anton Wolf, Philip Kaplan, George Madsen, Richard W. Giese e Claude Monteaux (Willoughby studiò principalmente con Joseph Mariano, tuttavia considerò il lavoro con Laurent come il più proficuo, cfr. http://robertbigio.com/willoughby.htm. Un’ampia lista degli allievi di Laurent è in (Fair 2003)), tale importante discendenza non sarebbe da considerare propriamente “Scuola americana”, Fair infatti la identifica come «Boston School», il cui insegnamento è più affiliato alla Francia.

Un altro flautista francese, che però non ebbe influenza didattica, fu René Rateau (1909-?), il quale, allievo di Gaubert, giunse a Boston nel 1938 per suonare presso la Boston Symphony Orchestra fino al 1939, nel biennio 1945-1946 stette presso la Minnesota Symphony Orchestra e dal 1946 presso la Chicago Symphony Orchestra sino al 1951, anno in cui tornò in Francia. Una situazione simile a quella vissuta da Laurent valse anche per René Le Roy e Marcel Moyse, i quali formarono una serie di allievi ritenuti in parte estranei, in parte ibridi rispetto alla discendenza di Barrére.

René Le Roy, in particolare, insegnò a molti flautisti americani in Francia e dopo numerosi tour negli Stati Unti trail 1929 e il 1940, decise di stabilirsi in Canada nel 1943, tornò in Europa nel 1950 e dal 1952 fu professore di musica da camera al Conservatorio di Parigi. Secondo De Lorenzo «René Le Roy has been a favorite in this country» (De Lorenzo 1992: 205).

A continuare idealmente l’insegnamento di Le Roy negli Stati Uniti, per altri dieci anni, fu il suo allievo inglese Geoffrey Gilbert nel momento in cui si trasferì nel 1969 in Florida, dove ancora oggi rimane memoria del suo lascito. Marcel Moyse, invece, si stabilì nel 1949 nel Vermont, anch’egli allievo di Taffanel come Laurent e Barrère, insegnò esclusivamente alla Marlboro Music School e, stando a Powell, iniziò ad acquisire maggiore visibilità negli Stati Uniti dopo la vittoria della sua allieva Paula Robinson al Concorso di Ginevra (Powell 2002: 243); altri suoi allievi americani furono: Robert Aitken, Carol Wincenc, Patricia Spencer, Jayn Rosenfeld e Judith Mendenhall (Hulbert 2011: 5).

Il dichiarato intento di Moyse fu quello di fondare una «Marcel Moyse School of Playing», «which I would still like to consider as mine» sui principi dei suoi maestri (Moyse in McCuthcan 1994: 193) ma, come testimonia Trevor Wye, la sua attività non ebbe particolare rilevanza nella formazione della tradizione americana del flauto:

There is no doubt that Laurent and Barrère taught talented students who became influential teachers, which formed the beginning of the American School of flute playing ‒ but it was not “The French School,” á la Taffanel, via Moyse .

Wye 1993: 107

La compresenza negli Stati Uniti di questi esecutori di Scuola francese, aventi alle spalle i medesimi discendenti, non fu collaborativa. Bernard Goldberg testimonia che «in some ways Barrère and Moyse were rivals, each one claiming to be the greatest flute player in the world» (Goldberg in Andrew 2002: 11).

La tesi di Demetra Fair Flutists’ Family Tree, che ricerca le radici della tradizione americana tra più di quattromila flautisti locali, ha dimostrato come la discendenza che ebbe la meglio tra questi esecutori francesi fu quella di Georges Barrère, da cui la grande maggioranza dei flautisti attuali trova le sue origini. L’ampia ramificazione di Barrère (Altri noti allievi di Barrère sono stati Samuel Baron (1925-1997), John Fabrizio, J. Henry Bové, Quinto Maganini (1897-1974), Meredith Wilson (1902-1984), Bernard Goldberg (1923-2017), Frances Blaisdell (1911-2009), Carmine Coppola (1910-1991), John Wummer (1899-1977), Maurice Sharp (1908-1986), Ernest Liegl (1900-1993), Paula Robinson (1941) e Arthur Lora (1903-1992), che fu successore alla cattedra di flauto del maestro presso l’Institut of Musical Arts. Liegl fu insegnante di Doriot Dwyer (1922), la prima donna a ricoprire il ruolo di primo flauto in una orchestra americana, la “Boston Symphony”, in sostituzione di Georges Laurent nel 1952.), tuttavia, è dovuta soprattutto all’influenza di un suo allievo nativo, che viene ritenuto il padre della Scuola americana: William Kincaid.

William Kincaid, caposcuola del flautismo americano

Of the 4360 flutists for whom an American-school ancestry is known, 3954 of these (approximately 91%) are Barrère descendant; 2576 (approximately 59%) are Laurent descendant; and 2387 (approximately 55%) are Moyse descendant. Of the 91% population who are Barrère descendant, an amazing 87% trace their ancestry through William Kincaid.

Fair 2003: 8

William Morris Kincaid (1895 – 1967) fu allievo di Barrère all’Institute of Musical Arts e si diplomò il 1 giugno del 1914 (Fair 2003: 51). Prese il posto di primo flauto nella “Philadelphia Orchestra” su raccomandazione del suo maestro, dove rimase dal 1921 al 1960, eccettuando il biennio 1928-29. Dal 1924 divenne insegnante nella città presso il Curtis Institute of Music, come anche altri esecutori della “Philadelphia Orchestra”. Ahmad riferisce la portata innovativa che ebbe Kincaid per i flautisti degli Stati Uniti, testimoniando un entusiasmo che si ritrova anche nel passo di Fitzgibbon pubblicato nel 1928 e citato in apertura:

The Philadelphian’s influence diverted many American flutists toward a different, bolder concept and away form the more intimate French style.

Ahmad 1980: 118

For many years William Kincaid was synonymous with the flute in the United States; he was America’s first virtuoso. Through his teaching at the Curtis Institute and his solo performances with the Philadelphia Orchestra, his influence on American flutists was enormous.

Ahmad 1980: 113

L’insegnamento, come la sonorità di Kincaid differivano da quelle del maestro Barrère, e certamente fu designato padre della Scuola americana in virtù del fatto che i suoi discendenti si riconobbero nelle sue qualità. John Krell afferma:

«To a great degree, he was responsible for developing a robust style that might be called the American school of flute playing»

Krill in Ahmad 1980: 114

La flautista americana Nancy Toff, allieva di Arthur Lora e Pappoutsakis, delinea chiaramente le qualità del suono di Kincaid, mettendole in relazione con quelle della moderna Scuola francese, sottolineando un nuovo uso del vibrato:

The true American style appear with the first generation of American-born orchestra principals, led by William Kincaid, revered elder statesman of the school. Kincaid’s tone was rich and robust, with great projection. Sometimes described as “virile”, it was heavier and darker than the traditional French sound. Like Barrère, Kincaid had a magnificent repertory of tone colors at his disposal, and he was an extremely careful but devoted and effective partisan of vibrato. In the American generations after Kincaid, little has changed in terms of basic tone ideals, with the exception that vibrato commands a good deal of pedagogical attention. The Barrère generation, in contrast, considered it a natural or instinctive technique, to be assimilated, not studied.

Toff 1996: 105

Nello stesso anno Donald Peck riportava in una intervista per The Instrumentalist:

We have such a short legacy ‒ just over 100 years of orchestral music in the U.S. ‒ and flutists no longer sound only like William Kincaid. Over the years the British flute players like Geoffrey Gilbert have also influenced us. The French have influenced style more than sound, but years ago the American flute sound was more French-oriented particularly because of Barrère and Laurent. However, it was Kincaid who pivoted from that, opting for a bigger, fuller sound. […] he may well have been the first to think about a change of sound; until then the flute was basically flutey. But Kincaid changed that by darkening the sound. […]. He told me that the fast, guttural vibrato was all flutists knew how to do in those early days, but with time they slowed it down to become more like a singer’s, with depth and body. His vibrato change coincided with his switch to a platinum flute, which darkened his sound.

Peck in Goll-Wilson 1996: 12-14

* Cfr. anche Toff sull’argomento, la quale definisce Kincaid: «the pioneer in developing a slower vibrato» (Toff 1996: 113).

Il suono di Kincaid era definito più scuro – favorito dal suo flauto in platino – con un maggiore volume rispetto ai flautisti della Scuola francese. Contrariamente alla tradizione da cui proveniva, introdusse all’imboccatura rilassata l’insufflazione delle guance e la posizione delle labbra con gli angoli rivolti verso il basso, misurava il vibrato e ne adottava una esecuzione più lenta che ‒ stando a Peck ‒ influenzò anche gli altri flautisti americani (Fair riporta: «When recalling his lessons as a student of Laurent, Willoughby remembers most vividly the free vibrato and beautiful sound of his teacher. Being a descendant of both Kincaid and Laurent, Willoughby also characterizes the “old French style” embouchure as tighter than that advocated by Kincaid (and Kincaid’s student Joseph Mariano), who proposed more flexible jaw movement and cheek inflation» (Fair 2003: 33):

Kincaid felt that a change in the concept of tone would help secure a more prominent position for the flute in the concerto repertoire. If the flute would project in a large auditorium, composers would feel more confident in writing for the flute… Kincaid wanted the flute to project, but he hated loud flute playing.

S. Kujala in Walker 1995: 7

Alla scomparsa di Kincaid, Aaron Copland accolse la richiesta degli allievi di scrivere una composizione, Duo for Flute and Piano (1971), per il compianto maestro, che in seguito venne definito «the most influential flute teacher of his generation, perhaps of his century, surpassing his own teacher in the rigor of his methodology and the sheer number of his students placed as orchestra principals» (Toff 2005: 129).

Gli allievi della scuola americana: Baker e Mariano

I due principali studenti della prima generazione, che ebbero una cospicua discendenza, furono Julius Baker e Joseph Mariano (Fair 2003: 8) (Altri allievi di Kincaid sono stati Robert Cole (1923-2016), Elaine Schaffer (1925-1973), John C. Krell (1915-1999), James Pellerite (1926), Kenneth Scutt (1923-2005), Harold Bennett, Burnett Atkinson, Albert Tipton, Irvin Gilman, Kenton Terry, Donald Peck, Charles Wyatt (1943) e Felix Skowronek (1935-2006).

Julius Baker (1915-2003) studiò inizialmente con il padre, nel 1933 si iscrisse al Curtis ma dovette passare alla Eastman sotto la guida di Leonardo De Lorenzo al momento della provvisoria chiusura dell’istituto per mancanza di fondi (Fair 2003: 61), riprese invece gli studi al Curtis nel 1934 con Kincaid che lo seguì fino al diploma.

Anche Joseph Mariano (1911-2007) si diplomò al Curtis nel 1935, e successe alla cattedra di Leonardo De Lorenzo presso la Eastman School of Music dove insegnò dal 1935 al 1974, mentre fu primo flauto alla “Rochester Philharmonic” dal 1935 al 1968:

A former student, now teaching at the University of Idaho, Patricia Dengler George remarks:“Mariano had a profound effect on the composers of America. His performances during the American Music Festivals […] developed a truly American style of flute playing. It was especially interesting to watch Mariano work during these festivals. He would be performing music that no one had seen or heard, yet his performance would be of an artistic level that made you sure he had known the music for years”.

May in Fair 2003: 67-68

L’eredità della scuola francese negli Stati Uniti

Bisogna quindi prendere nota del fatto che, nell’individuazione degli antenati della Scuola americana, non venga considerato nessun flautista che non sia di Scuola francese: l’enorme lavoro di Demetra Fair, Flutists’ Family Tree: in Search of the American Flute School, che indaga su quale corrente di insegnamento del flauto gli Stati Uniti facciano riferimento, infatti, non considera affatto la discendenza di Leonardo De Lorenzo, ma conclude che sia la Francia ad aver prodotto i maestri più influenti, che risultano essere dalla sua ricerca l’esclusiva maggioranza.

«For American flutists, therefore, Independence Day truly occurred on May 13, 1905, when Barrère arrived in New York»

Toff 2005: 315

La musicologa e flautista americana Nancy Toff è molto chiara nel parafrasare quello che ha significato Barrère per gli Stati Uniti: ha portato il flautismo degli strumentisti locali alla pari dei colleghi europei. È così che l’arte e la lingua francese tornarono ancora ad essere baluardo e promotrici de “La Liberté éclairant le monde” (Carl Engel, direttore della “Library of Congress Music Division”, si espresse su Barrère nei seguenti termini: «France, in letting the great flutist come to America, made an impressive gift of greater significance than when the Statue of Liberty was erected in New York Harbor» (Engel in Toff 2005: 326))

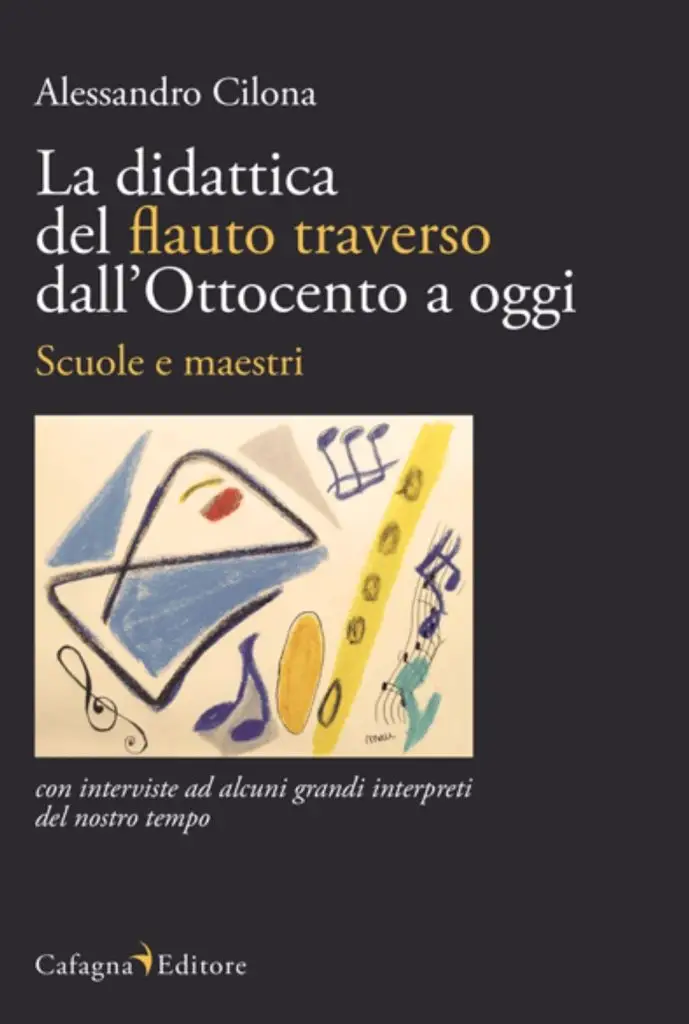

Il presente libro ricostruisce per la prima volta le principali tradizioni didattiche nazionali per il flauto, ripercorrendo la storia dell’estetica acustica e organologica dello strumento a partire dalla fine del XVIII secolo fino alla seconda metà del Novecento a fronte della diffusione discografica e della globalizzazione.

La storia delle idee, delle istituzioni musicali che hanno promosso e ospitato la tradizione artistica, nonché la produzione letteraria e didattica, vengono osservate e analizzate all’interno del loro contesto storico di realizzazione. I principali esecutori e maestri del passato flautistico sono di volta in volta presentati mostrando il loro peculiare contributo per la storia dello strumento e ricostruendo il rapporto con il contesto musicale dell’epoca e la trasmissione agli allievi. “Alberi genealogici” stilati per ogni Scuola, interviste ai maestri e una discografia di riferimento arricchiscono ulteriormente un testo unico e innovativo negli studi del settore.

“The Pedagogy of the Flute from the 19th Century to Today” by Alessandro Cilona

Alessandro Cilona’s La didattica del flauto traverso dall’Ottocento a oggi offers the first comprehensive exploration of national pedagogical traditions for the flute. This groundbreaking work traces the evolution of flute aesthetics, acoustics, and organology from the late 18th century to the second half of the 20th century, a period shaped by the rise of recordings and globalization.

The book meticulously examines the historical context in which key musical ideas, institutions, and pedagogical methods emerged, shedding light on the artistic traditions that defined flute performance. Through a detailed analysis of prominent flutists and teachers, Cilona highlights their unique contributions to the development of the instrument and their influence on subsequent generations. Each figure is placed within the broader musical landscape of their time, revealing the lineage of knowledge passed down to students.

What sets this work apart are the genealogical charts that map the lineage of major flute schools, insightful interviews with leading teachers, and an essential discography that serves as a reference for both performers and researchers. This innovative and richly detailed study is an invaluable resource for understanding the evolution of flute pedagogy, offering a fresh perspective for scholars, flutists, and music educators alike.

– Flute Almanac

Alexander Cilona

The transverse flute | Creation and diffusion of an instrument in its symbolic and social context

Meraviglioso viaggio nel flautismo che ci ha condotti fino ad oggi.

Grazie del bel dono.

Grazie per aver apprezzato!

Ottimo viaggio a volo d’uccello sul flautismo francese in USA. Questo tuo studio supera la visione retorica di Gian Luca Petrucci sull’influenza di Leonardo De Lorenzo sul flautismo USA, quasi ne fosse il motore generatore. Petrucci nella sua enfasi ha sopravvalutato De Lorenzo , mentre ha trascurato altri tasselli importanti del flautismo italiano in USA (come Clemente Barone che fu conterraneo e cronologicamente parallelo a De Lorenzo essendo nato a Marsico Nuovo in provincia di Potenza ed essendo attivo a Filadelfia, con una notevole attività solistica discografica per la Victor).