Setting the Scene

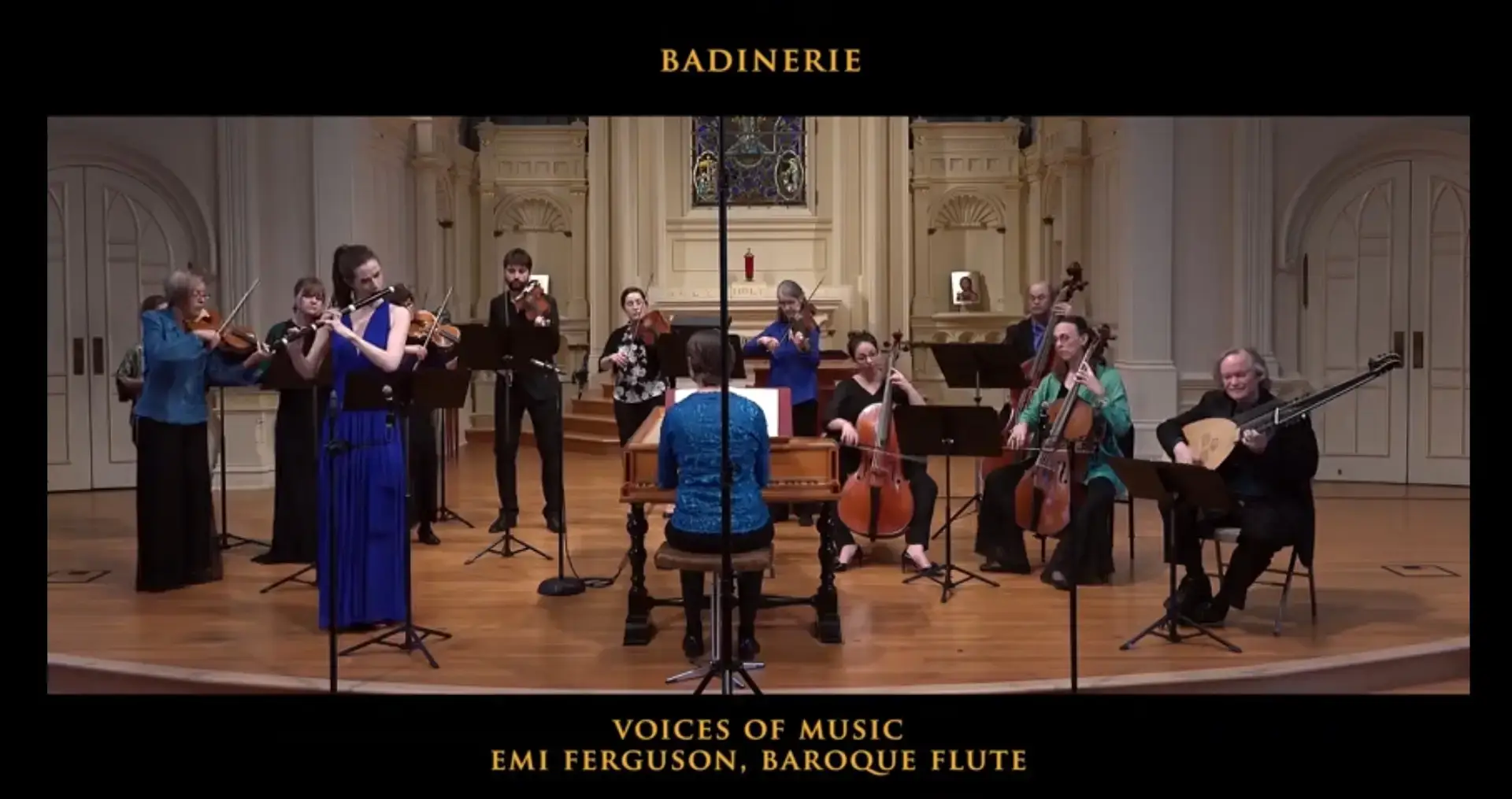

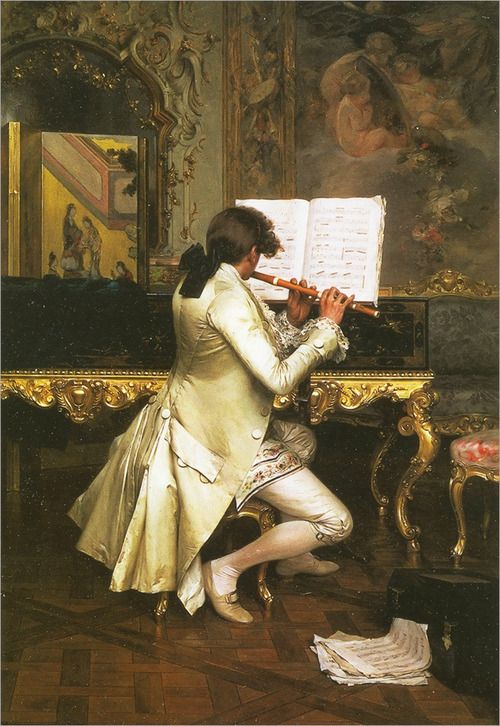

It is an early summer morning, somewhere in Europe in 1745. Perhaps Dresden, where the Prussian court cultivated a glittering musical life under Frederick the Great. Or perhaps Paris, with its salons, operas, and the fashionable demand for traverso players.

A young flutist sets down his single-keyed flute on a linen cloth. A cup of warm infusion waits nearby. The shutters are half-open, letting in slanted morning light.

No metronome ticks. No tuner app glows. No bound etude books exist. The ritual begins in silence. The flutist begins with breath itself: inhale, exhale, the quiet placement of air into sound. Then tone. A pause. A trill, testing the balance between freedom and control.

This moment is more than “warming up.” For the Baroque musician, practice was never just technical conditioning. It was an exercise of mind, ear, taste, and character.

As Johann Joachim Quantz insists in his Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752), Cap. X §6:

“Nicht allein die Finger, sondern auch der Verstand und das Gehör müssen arbeiten.”

(Not only the fingers, but also the mind and the ear must work.)

With this mindset, we can reconstruct what a daily session of practice might have looked like in the 1750’s, drawing on the testimony of Quantz, Hotteterre, Leopold Mozart, Mattheson, Geminiani, Heinichen, Tosi, and others.

Themes of Historical Practice

1. Practice Is Mental, Not Just Physical

The 18th century knew the danger of mindless repetition. Modern musicians often equate practice with clocked hours and technical drills. The Baroque writers reject this. For them, practicing without active listening was not only useless — it was damaging.

Leopold Mozart cautions violinists in his Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756), Chap. II §6:

“Zu vieles und unüberlegtes Spielen ist mehr schädlich als nützlich.”

(Too much and thoughtless playing is more harmful than useful.)

Paraphrasing Francesco Geminiani, in The Art of Playing on the Violin (1751), he advises:

“Don’t just train the hand, train the ear and taste first”.

The message is clear: practice involves engaging both body and perception, rather than repetitive routine. Silence, pauses, and even daydreaming were part of practice—not interruptions, but essential phases in the shaping of musical understanding.

2. Variety Over Repetition

The idea of “an hour of scales” would have been absurd to Quantz. He rails against monotony, urging players to diversify material and rhetorical intent.

Practice was built in blocks:

- tone and intonation;

- articulation, sometimes spoken aloud without the flute;

- ornaments in slow isolation;

- expressive lines borrowed from vocal models;

- improvisations, even miniature ones.

Each segment carried a different mental focus. The point was not sheer endurance but freshness — stopping before the hand or mind dulled.

This practice architecture, flexible but deliberate, feels surprisingly modern in light of today’s emphasis on distributed learning and interval training. What neuroscience now calls “interleaving” and “spaced repetition” was already embedded in 1745.

Quantz, ever the careful pedagogue, is explicit in Versuch, Cap. X §8:

“Die Übung muß nicht bloß auf das Spielen allein, sondern auch auf den Geschmack, den Vortrag und die Manieren gerichtet sein.”

(Practice must not be directed only toward playing, but also toward taste, delivery, and ornamentation.)

Johann David Heinichen, in his Der General-Bass in der Composition (1728), insists:

“Der General-Bass ist das wahre Fundament der Music, und überhaupt aller Composition, des Singens und Spielens.”

(The thoroughbass is the true foundation of music, and of all composition, of singing and of playing.)

And Pier Francesco Tosi, in Opinioni de’ cantori antichi e moderni (1723), translated as Observations on the Florid Song, Part 1, Chapt.II, instructs:

“Let not the Scholar pass to a second Lesson, till the first is well fix’d in his Memory.”

This was the pedagogy of depth and focus. Repetition was avoided; variety was cultivated.

3. Expression Before Perfection

The 18th century distrusted “mere virtuosity.” Technique without expression was a frequent target of scorn. Le Blanc warns of the “virtuoso without soul.” Mattheson compares performance to speaking p— persuasive, rhetorical, intimate. Hotteterre, ever pragmatic, insists the player must first master articulation with the tongue alone, before even lifting the flute.

This inversion of priorities is striking. Instead of scales leading to music, music—rhetoric, affect, speech — shaped the scale. A scale was not a neutral pattern. It was colored by mood: bright, tender, severe, lamenting.

Practice, then, was not the suspension of artistry until later. It was artistry from the very first note.

Hubert Le Blanc, in Défense de la basse de viole contre les entreprises du violon et les prétentions du violoncelle (1740), warns:

“On doit distinguer Poësie & Prose dans la Musique. … Le caractère de la Poësie Musicale est le Chant.”

(One must distinguish poetry and prose in music. … The character of musical poetry is song.)

Johann Mattheson, in Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739), writes:

“Der Vortrag ist gleichsam eine Rede.“

(Performance is, as it were, a speech.)

Jacques Hotteterre, in Principes de la flûte traversière (1707), gives the pragmatic foundation:

“Pour rendre le jeu plus agréable et éviter trop d’uniformité dans les coups de langue, on les varie de plusieurs façons.”

(To render playing more agreeable and avoid too much uniformity in tongue strokes, one varies them in several ways.)

And Geminiani again:

“The Intention of Musick is not only to please the Ear, but to express Sentiments, strike the Imagination, affect the Mind, and command the Passions.”

In practice, this meant that even scales were charged with affect. They were not neutral patterns but “spoken” gestures. A scale might sound sorrowful, noble, or tender, depending on rhythm and articulation.

4. Rest, Reflection, and Rhetoric

Far from advocating endless hours, most writers describe practice as punctuated, thoughtful, and often short.

Quantz himself, serving the rigorous Frederick the Great, counsels balance, in Versuch, Cap. X §3:

“Die unermüdete Fleißigkeit muß nicht mit einer blinden Leidenschaft, sondern mit Überlegung und Vernunft verbunden werden.”

(Unflagging diligence must not be paired with blind passion, but with reflection and reason.)

Practice was therefore a cycle: play, listen, reflect, rest, resume. Coffee, poetry, or the study of vocal models provided renewal. Musicians cultivated their art not only by touching the flute, but by listening, reading, and imagining.

A Modern Reconstruction

What could this look like for us today, traverso in hand? If we translate these principles into a 21st-century Baroque flute practice session, it might look like this:

1. Morning Tone Ritual

- Long tones shaped like vowels (a, e, u).

- Intervals tuned for resonance: fifths, octaves, thirds.

- Subtle ornaments added like spices, never routine.

2. Spoken Articulation

- Recite “tu, du, ru” aloud, shaping syllables as speech.

- Read lines of poetry aloud for rhythm and inflection.

- Only then let the flute mirror the speech.

3. Scales with Affect

- Major/minor scales, but imbued with character (joyful, melancholic, severe).

- Cast them in dance rhythms (a sarabande-scale, a gavotte-scale).

4. Ornament Laboratory

- Focus on one ornament: trill, appoggiatura, slide.

- Vary tempo, emotion, and context.

- Compare fingerings; explore slow, fast, playful, sorrowful versions.

5. Rhetorical Piece

- Choose a short air or recitative.

- Memorize a phrase, shape it like a sentence.

- Improvise a variation in the same affect.

6. Reflection & Cool-down (5 min)

- Slow, unmeasured line.

- Concentrate on the sheer beauty of tone.

- Ask: what affect did I discover today?

Final Thoughts: Practicing Like a Philosopher

For the flutist of 1750’s, practice was not a mechanical grind. It was a rhetorical and ethical act. The traverso was not simply an instrument—it was a voice, a vehicle of persuasion and taste.

In our own time, it is tempting to measure practice by duration, or to reduce it to technical gains. But the testimony of Quantz, Mozart, Geminiani, Hotteterre, Mattheson, and others calls us back to another vision: practice as a philosophical exercise, as a training in reflection and expression.

The central question is not: “How much can I play today?”

It is: “How deeply can I listen, explore, and move?”

Francesco Belfiore

www.traversopractice.net | Facebook Page | Youtube

Francesco Belfiore is a lifetime flute enthusiast, amateur and researcher.

In 2022 he started the Traverso Practice Net, an open-access multimedia sharing platform, with the aim to fill existing gaps in baroque flute practice at all levels.

In just over a year, the platform has gained global traction and extensive recognition.

The website has had more than 9,000 visitors from all over the world and the Facebook community counts nearly 1,000 followers.